My Life So Far (74 page)

I sat at his feet and told him that I loved him very much; that although things had not always been good or easy between us, I knew he had done his best to be a good father; that I loved him for it and was sorry for things I had done that had hurt him. I also told him how much I appreciated the way Shirlee looked after him—above and beyond the call of duty; all the nurses said they’d never seen a wife like her—and that no matter what, we would always consider her a part of our family and would keep her close. I don’t remember him saying anything, but he began to cry. I didn’t know if it meant he was moved because I had spoken of love and forgiveness or if my words showed him that I knew he was dying and that perhaps this was the first time anyone had said these closure words to him.

There is a saying that we all repeat often to explain our family members’ readiness to tear up over silly things: “Fondas cry at a good steak.” It’s one thing to get teary over a good steak and another to weep from the depths of your heart—that display of emotion was what my father always hated, because he felt it showed weakness. Except for when Roosevelt died, I had not seen him cry from that deep place, and I hurt for him and was scared of this display of his pain and sadness. I stayed for a while in an effort to comfort him but then had to leave because I could sense that he hated to be crying in front of me. Shirlee told me that when she got home a little later she found him still in the chair, sobbing.

Then one morning Shirlee called me to come quickly to the hospital. I prayed I would get there while he was still alive, but he had died three minutes before. It doesn’t matter how long a loved one has been near death, when it finally comes you never feel prepared. I wanted to sit by his bed and look at him for a long time. I

needed

to look at what there was, now that his soul had left, and to think about that. I needed closure. But the nurse officiously asked us all to leave the room so they could clean him up.

I went home and picked up Tom and the kids and we all drove to Dad’s house to be with Shirlee. The press was already gathered outside their Bel-Air driveway, interviewing friends as they came to pay their respects. Slowly they gathered: Jimmy Stewart, Eva Marie Saint, Mel Ferrer, Dad’s very first leading lady from Omaha, Dorothy McGuire, Joel Grey, James Garner, Lucille Ball, Barbara Stanwyck. My brother and his wife, Becky, came, with his daughter, Bridget, and son, Justin.

That first afternoon, when the house was crowded and everyone was in deep shock trying to wrap their minds around the reality that he was gone from us, I remember sitting in the study across from Jimmy Stewart. On his way in he had told the press, “I’ve just lost my best friend.” He had been sitting across from me with his head hanging down for several hours, without saying a word, when a movement from his direction caught my attention. Jimmy was lifting his arms up over his head and it dawned on me that he was remembering the kite that he and my dad had once made together, and he was trying to describe its enormity. I remembered Dad telling us the story of this kite when he and Jimmy were in their late twenties in California. Jimmy didn’t seem to be talking to anyone in particular; he wasn’t even paying attention to see if anyone was listening. He was just totally wrapped up in his memory: “It was so big . . . this big”—his arms went higher and his hands wider—“and . . . and”—Jimmy was always a stammerer—“when it caught the wind, it pulled me off the ground.” He smiled. Then his arms came down and he was again silent. Those of us in the room looked at one another, understanding what a unique and deep loss this was for Jimmy. He seemed to enjoy it when I got him to reminisce about the days in New York during the Depression when the two of them had lived on rice.

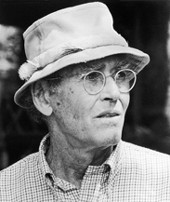

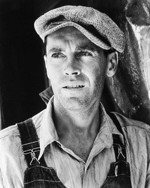

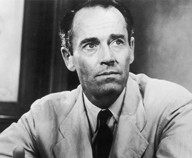

The faces of my father that I loved: center is Norman Thayer, clockwise from bottom left: Abraham Lincoln, Tom Joad, Gil Carter

(Ox-Bow Incident),

Mr. Roberts,

Juror #8

(12 Angry Men),

Clarence Darrow.

(Photofest)

I sat for a while next to the man who had been Dad’s makeup artist for many years. He told me how much Dad talked about me, worried about me. “You can’t imagine how much he talked about you.”

Funny, I thought, how Dad talked to others

about

me but never directly

to

me, unless there was a problem. And I wondered if maybe I wasn’t guilty of this with regard to my own children.

Not having been able to mourn my mother’s death, and never again wanting to have internal tears that can’t come out, I made a conscious decision that I would allow myself to experience fully Dad’s passing. I moved into the house with Shirlee and did not leave for a week. For days people kept coming by to pay their respects. We’d sit together and watch his eulogies on television—all week they went on. It hit me that this wasn’t just my loss, the family’s loss. It was a national loss. Dad was a public figure, a hero, who didn’t belong just to us. Dad lived out these quintessential American values. He represented things that we all want to be and that the

country

wanted to be. He often said he was attracted to certain kinds of roles—the working poor, powerless people, and the men who helped them get some power for themselves—because somehow their characters might rub off on him and he would become a better person. But now I saw that there had been a dialectic; he

did

have many of those qualities.

One of the things I learned during that time was how courtesies matter. I had often not written to people I knew when they had lost a loved one, because I didn’t really know what to say. Now I was seeing that just getting a letter, whether articulate or not, matters; it lets you know that the person is mourning with you, countenancing your pain. There were two letters especially important to me; one was from Carl Dean, Dolly Parton’s husband, who wrote movingly of his admiration for my father; the other was from Gary Cooper’s daughter, Maria, who spoke of the complexities of dealing with the loss of a father who was also a national hero.

I spent a lot of time in Dad’s garden during those days of mourning, sitting under one of his fruit trees sorting out my feelings. While I still had a long way to go, in hindsight I see that this was a first step in my learning to be still, to

be

and not to

do.

I was grateful for having had

On Golden Pond

with him and that I’d managed to tell him I loved him before it was too late. I could feel myself making peace with the fact that though he hadn’t given me all I had needed from him, he’d given me plenty. I somehow sensed that now that he was gone, some part of me would be able to come into its own, though I couldn’t quite put my finger on what it would be. I was sad that at his request there would be no memorial service, that he would be cremated but never buried. I like graves, always have. They give a tangible presence to the spiritual realm. I knew that there would be times when having a gravestone to sit by and touch would make it easier to remember and communicate with him. But it wasn’t my decision to make. This was when I decided I wanted to be buried with a gravestone, where my kids and grandkids could come and lay down their heads.