Modern China. A Very Short Introduction (9 page)

Read Modern China. A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

Yan’an was not easy to get to, its isolation being an advantage in protecting the area from the Nationalists and the Japanese. Mao took advantage of this, using the period to implement a variety of policies that would eventually infl uence his rule over China.

These included attempts to create a self-suffi cient economy, tax and land reforms to relieve the poverty of the rural population, 50

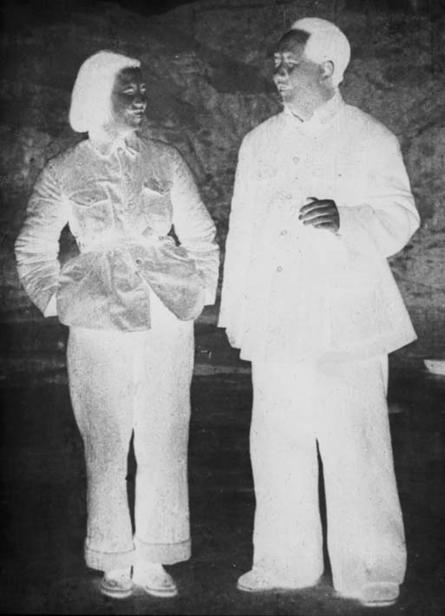

8. Communist leader Mao Zedong and his wife Jiang Qing (taken after

the Long March, 1936)

51

and fuller representation for the local population in government.

At the same time, Mao reshaped the party in his own image. The Party was purifi ed through repeated ‘Rectifi cation’ (

zhengfeng

) campaigns, which sought to impose an ideological purity on party members based in Mao’s own thought, rather than encouraging dissent.

The American journalist Edgar Snow, who sympathized deeply with the Party, travelled to Yan’an and met Mao. In his classic account of that journey,

Red Star over China

, he noted of Mao:

He had the simplicity and naturalness of the Chinese peasant, with a lively sense of humor and a love of rustic laughter … he combined curious qualities of naivete with incisive wit and worldly sophistication.

hina

By the end of the war with Japan, the Communist areas had expanded massively, with some 900,000 troops in the Red

Modern C

Army, and Party membership at a new high of 1.2 million. For much of the 1930s and into the war years, it was clear that there were two major ideological poles for nationalists who opposed the Japanese presence: Chiang’s government at Nanjing (then Chongqing, during the war), and Mao’s at Yan’an. Both of these offered a powerful vision of modernity, in both cases at odds with the somewhat ramshackle reality of their areas of control. But greater power for one pole sucked it away from the other: in the mid-1930s, the Nationalist pole seemed to be gaining strength, but by the mid-1940s, war and its effects had reversed the balance.

Above all, the war with Japan had helped the Communists come back from the brink of disaster, and destroyed the tentative modernization that the Nationalists had undertaken. In the aftermath of Japan’s defeat, both sides scrambled for power.

Unable to reach a compromise, the Nationalists and Communists 52

Victory in Chongqing

In the centre of the city of Chongqing you will fi nd a tall

piece of statuary, now rather dwarfed by the glass and

steel skyscrapers surrounding it. This is the Liberation

Monument. There are many references to ‘liberation’

(

jiefang

) in China today, but almost all these references are

to 1949, the year that the Communists fi nally gained control

of the Chinese mainland. But in Chongqing, the Liberation

Monument commemorates another event: the victory over

Japan in 1945. It was this moment that marked the turning

point. What sort of country would postwar China be?

It is worth remembering the assumptions of most Chinese

and of the world at large on that day. It was not Mao but

Chiang Kaishek, as China’s leader through eight years of war,

Making C

who received the world’s accolades, and held victory parades

through his wartime capital at Chongqing. The assumption

hina modern

of Chiang, and the world, was that his government would now

take up the state-building project that he had begun in the

1920s.

The West certainly assumed that Chiang would be in

power for years. President Roosevelt had characterized

China as one of the Four Policemen (along with the US,

USSR, and Britain) that would monitor the postwar world.

Prime Minister Churchill had far less enthusiasm for

treating Chiang as a serious global fi gure, but he did not

see him losing power. Certainly, China’s determination

to last out through the war had reaped rewards on the

global stage. In 1943, all of the ‘unequal treaties’ that had

plagued Chinese-Western relations for a century had

fi nally been ended. In 1946, China would become one of

the fi ve permanent members of the Security Council of the

new United Nations. Huge international aid efforts were

made to relieve the desperate poverty in China’s cities and

53

countryside. The assumption on all sides, including Stalin’s

USSR, was that China would remain in the Western bloc in

the emergent Cold War.

Within years, it all went wrong for Chiang. Why? Most

histories have laid the blame squarely at the feet of Chiang

and the Nationalists, and they must surely take a large part

of the responsibility. Large swathes of the population were

branded as collaborators, with little understanding shown for

the dilemmas that had faced those who had to decide whether

to fl ee or stay in the face of Japanese invasion. Many of the

offi cials installed in the restored Nationalist government

were corrupt and ineffi cient. Within months, the goodwill of

victory was being squandered.

Was the Communist victory a military one or a social one?

The two aspects are not easily separated. The CCP had little

hina

chance to implement serious land reform before 1949 in most

areas of China: during the Civil War, it simply did not have

Modern C

that level of control over the population. Without the brilliant

military tactics of Lin Biao and the other PLA generals,

social reform on its own would not have been enough to

bring the CCP victory. On the other hand, it was clear by

1948 that while Chiang’s armies had the support of the US

and superiority in terms of fi nance and troop numbers, their

morale was slipping away. The goodwill from victory over

Japan had not been transferred to the CCP, but it was no

longer with the Nationalists. Their chance for unity had been

squandered.

By the time Mao declared the establishment of the People’s

Republic of China (PRC) on top of the Tian’anmen in 1949,

China’s path was not in doubt. The year 1949 was not a

turning point, but the result of choices made in 1945: China

was going to have a communist government allied to the

USSR and closed to the West.

54

plunged into civil war in 1946, a war ended only by victory for the CCP in 1949. Chiang fl ed to Taiwan, and in Beijing, now restored to its status as the capital, Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

Mao in power

Mao’s China was very different from Chiang’s in a variety of ways.

Perhaps, overall, the most powerful change was encapsulated in the slogan ‘Politics in command’, which was used during the Great Leap Forward campaign of 1958-62. Chiang had been concerned to create a politically aware citizenry through campaigns such as the New Life Movement, but these had failed to penetrate very successfully. Mao’s China had much greater control over its population, and did not hesitate to use it. Its politics was

Making C

essentially modern, in that it demanded mass participation in which the citizenry, the ‘people’, saw itself as part of a state project based on a shared class and national identity. The success of Mao’s

hina modern

military and political tactics also meant that the country was, for the fi rst time since the 19th century, united under a strong central government.

Mao’s China is often characterized as isolated. It is certainly true that most Western infl uence was removed from the country; the large numbers of businessmen, missionaries, and educators – many of whom had spent their lives in China – were almost all expelled by 1952. However, China was now exposed to a new sort of foreign infl uence: the new dominance of the Soviet Union in the still-emerging Cold War. The 1950s marked the high point of Soviet infl uence on Chinese politics and culture: Soviet diplomats, technical missions, economists, and writers all played their part in shaping the new communist China. Yet, the decade also saw rising tension between the Chinese and the Soviets, fuelled in part by Khrushchev’s condemnation of Stalin (which Mao took, in part, as a criticism of his own cult of personality), as well as cultural misunderstandings on both 55

sides. The differences between the two sides came to a head in 1960 with the withdrawal of Soviet technical assistance from China, and Sino-Soviet relations remained frosty until the 1980s.

The People’s Republic used its state power in one way that was very different from the aims of Chiang’s China: the pursuit of class warfare. Mao had fi nally risen to undisputed leadership of the CCP during the war period, and his writings made it clear that when he fi nally gained power, moderation and restraint were to be shunned. ‘Revolution’, he famously claimed in 1927

in his

Investigation into the Peasant Question in Hunan

, ‘is not a dinner party … it cannot be so refi ned, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous.

A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.’ Certainly, the years of war and the failure of the Nationalists genuinely to reform social relations

hina

in rural China meant that there was a widespread constituency in favour of violent change, driven by a conviction that

Modern C

previous attempts to change the structure of rural society had failed.

The initial period of ‘land reform’ in China in 1949–50 saw some 40% of the land redistributed, and some 60% of the population benefi ting from the change. Perhaps a million people who were condemned as ‘landlords’ were persecuted and killed. Yet this violence was not random. Offi cial campaigns were instigated that oversaw and encouraged terror. The joy of ‘liberation’ was real for many Chinese at the time; but the early 1950s were not a golden age when China was truly at peace.

The urgency came from the continuing desire of the CCP to modernize China. The PRC had to deal with the reality of its situation in the early Cold War: the US refused to recognize the government in Beijing, and although other Western 56

Making C

9. Land redistribution in the early 1950s was a time of joy for many

peasants, but it also led to a deadly terror campaign against those

hina modern

judged to be ‘landlords’. The landlord in this picture, taken in 1953,

owned around two-thirds of an acre

countries did open up diplomatic relations, the country was economically relatively isolated, even though it now had a formal cooperative relationship with the USSR. When relations with the Soviets also started becoming chillier in the mid-1950s, as Mao expressed his anger at the Khrushchev thaw, the CCP

leaders’ thoughts turned to self-suffi ciency as an alternative.

Mao proposed the policy known as the Great Leap Forward.

This was a highly ambitious plan to use the power of socialist economics to increase Chinese production of steel, coal, and electricity. Agriculture was to reach an ever-higher level of collectivization, with individual plots (the basis of the popular land reforms of Mao’s fi rst years in power) being subsumed into large collective farms. Family structures were broken up as communal dining halls were established: people were urged to 57

eat their fi ll, as the new agricultural methods would ensure plenty for all, year after year. The Minister of Agriculture, Tan Zhenlin, declared:

After all, what does Communism mean? … First, taking good food and not merely eating one’s fi ll. At each meal one enjoys a meat diet, eating chicken, pork, fi sh or eggs … delicacies like monkey brains, swallows’ nests, and white fungi are served to each according to his needs …

The plan was fuelled by a strong belief that political will combined with scientifi c Marxism would produce an economic miracle of which capitalism simply was not capable. Yet its goal was unquestionably one of modernization through industrial technology. The stated goal of the Leap was to overtake Britain in 15 years, and by this, it was Britain’s industrial capability, not its wheat fi elds or cattle, that was meant. The Leap has been

hina