Modern China. A Very Short Introduction (18 page)

Read Modern China. A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

China’s hinterland had always been underpopulated for a good reason: it was arid land incapable of producing many crops. Now that offi cial policy is to ‘open up the west’, the problem of water supply must be solved. Unfortunately, there have been cases of rivers in western China that traditionally fl owed downstream into Southeast Asia being diverted to water western China, leaving parts of Vietnam dry. The prospect of ‘water wars’, virtual or real, is in the minds of governments around the region. Most of all,

hina

China is expected to become the world’s largest emitter of carbon into the atmosphere by 2008, and is contributing to massive

Modern C

global warming in the process. China’s middle class is still small compared to its much poorer rural population. When the latter become richer, and when China’s very high national savings rate reduces as consumers start buying more, the effects on the global environment could be catastrophic.

Another persistent problem remains: lack of transparency and the corruption that comes along with it. It is still illegal to reveal

‘state economic statistics’, including basic economic information that would be public in many economies. The organization Transparency International releases an annual survey of perceived corruption around the world: in 2006, China scored 3.3 (on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being least corrupt), the same score as India, which placed both countries around midway in the table, below New Zealand (9.6) and the US (7.3) but above Vietnam (2.6) and Pakistan (2.2). China’s operation of law is still instrumental rather than principled. Though various aspects of 116

corporate and criminal law have been revised, often with some operational success, the Party still stands above the law, making it hard to operate the ‘rule of law’ in the classic sense.

Conclusion

Is China’s economy part of the modern world? In some ways, it seems to refl ect assumptions very different from the espousal of free markets and withdrawal of the state that were heard in the West in the 1990s and beyond. The state and party are heavily involved in the Chinese economy, as well as its overseas investments, and the market is still hard for outsiders to penetrate despite China’s entry to the WTO in 2001. Corruption and lack of transparency cloud attempts to divine the real story of what is happening in China’s economy. Yet China’s economy now matters

Is C

hina

to everyone in the world – in manufactured goods, fi nancial

’s ec

services, and currency and interest rates, China’s infl uence

onom

is undeniable. While adapting to the world of the modern, globalized economy, China has also forced the world to reshape its

y modern?

economy, at least in part, to Chinese needs.

117

Is Chinese culture modern?

In 1915, the response of radical intellectuals to the fear that president Yuan Shikai would declare himself as a new emperor was to propose the idea of a ‘new culture’. The same language, but a very different argument, was used by Mao during the Cultural Revolution more than half a century later. The idea that somehow China’s culture had contributed to its uneasiness with the modern world has persisted from the time of the Opium Wars up to the present day. Yet contemporary Chinese writers are translated and praised around the world; their fi lms win prizes at international fi lm festivals; and Chinese artists command huge prices at auction in the global art market. The quest for a culture that is simultaneously modern but also derived from Chinese desires and inspirations continues to be at the centre of the Chinese artistic endeavour.

The origins of modern readership

Writing has, from the earliest times, been valued in Chinese culture. Yet for centuries, reading remained a largely elite and male skill. An important part of the modernization of Chinese literature was its engagement with a mass audience and its use of technology to reach that audience. In this process, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) was important, because it saw an immense rise in the consumption of high and popular culture. China was 118

at peace and became more prosperous, and this fact allowed a market for education, as well as for luxury goods and services, to emerge. In addition, new technology allowed particular types of product to develop, such as woodblock prints and popular novels, which could now be printed in huge numbers. The Jesuit monk Matteo Ricci in the 17th century noted the care and skill involved in creating a woodblock, observing that a skilled printer could make some fi fteen hundred copies in a single day.

The high Ming and Qing dynasties saw an interest also in connoisseurship, as well as mass-produced culture. The city of Yangzhou, in particular, became known during the Ming as a centre where ‘the people by local custom value scholarship and refi nement, and the gentry promote literary production’. In addition to a love of fi ne books, calligraphy, and painting, the

Is C

cultivation of rare plants and acquisition of exotic fruits could

hinese c

be a sign of taste. Such connoisseurship would decline with

ulture modern?

the economic crisis of the late Qing, and the collective politics and ideologically and militarily driven austerity of much of the 20th century also frowned on the cultivation of such luxurious tastes. Only in the 1990s did the depoliticized, consumerist urban economy in China once again encourage personal collections of art.

The end of the imperial era also proved a watershed for both high and popular culture in China. Perhaps the most notable change in Chinese written culture in the early 20th century was the language reform of the 1910s and 1920s. In the late imperial era, classical Chinese was still used for offi cial documents and works of literature and history. But the spoken language had developed over centuries since the classical form was used, and popular writing, such as novels, plays, and unrespectable writing such as pornography were instead written in a vernacular form of Chinese that refl ected the spoken language. By the early 20th century, many reformers felt that it would not be possible for China to progress unless its written language was brought into harmony 119

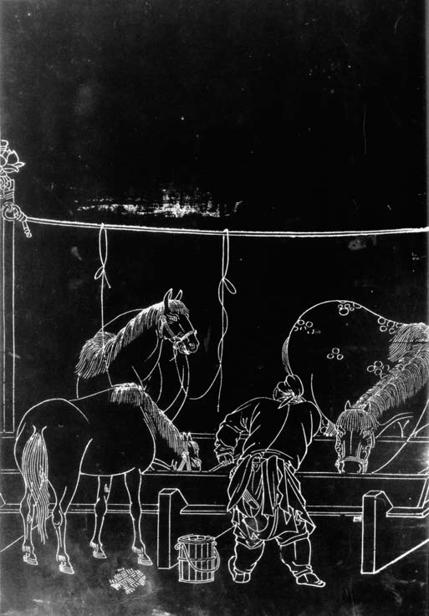

18. Reproduction of a section of the ‘Nine Horses’ scroll by Ren Renfa,

from the book

Master Gu’s Pictorial Album

(1603). During the Ming

dynasty, art was reproduced for a wider audience to purchase and

appreciate

120

with its spoken form. Hu Shi (1891–1962), who had studied in the US, and then took up a teaching position at Peking University, was particularly instrumental in this movement. Despite China’s disunited state in the 1910s, the language reform movement was highly successful. At the time of the 1911 revolution, it was still normal for newspapers and school texts to be in a simplifi ed form of the classical language; by the mid-1920s, it was the

baihua

(vernacular) form which had supplanted it almost entirely. This change also had a major impact on Chinese literature, which was almost entirely written in vernacular Chinese by the late 1920s. It is hard to overestimate the change made by this shift in Chinese culture; the arrival of an offi cially recognized vernacular form of written Chinese paved the way for mass literacy and the ability of the state to use education and propaganda to engage with its population (most notably under the CCP).

Is C

hinese c

May Fourth and its critics

ulture modern?

The interwar years have come to be regarded as the single most important period in the development of modern Chinese literature. The era is sometimes characterized as the ‘May Fourth’

period, a reference to the patriotic outburst that emerged in protest at the Treaty of Versailles (see Chapter 2), and fuelled a powerful rethinking that became known as the ‘New Culture’.

The literature of the New Culture period is notable for its tone of constant crisis. It was the product of a China in fl ux: the new Republic was less than a dozen years old, yet had already fallen victim to warlordism; Chinese society was still racked by poverty; and women and men were trying to fi nd new ways to relate to each other. The writers used their fi ction to deal with the pressing problems of a China trying to come into modernity. Many of these authors, including Lao She, Lu Xun, and Qian Zhongshu, lived and worked abroad, and brought global infl uences into their work.

121

The writer even now generally considered to be modern China’s fi nest was Lu Xun (1881–1936), the pen-name of Zhou Shouren.

Lu Xun’s earliest short stories are notable for their savage condemnation of what he saw as the nature of Chinese society: inward-looking, selfi sh, and self-deluding. In

The True Story

of Ah Q

, the anti-hero Ah Q is beaten up by his employers, rejected in love, and eventually wrongly accused of a robbery and executed: but all the time, even on his way to his death, he is convinced that he is making great progress in life. Ah Q is a Chinese everyman, but rather than a sympathetic ‘little man’

fi ghting against greater forces, Lu Xun makes it clear that Ah Q

is a petty and vainglorious jackanapes, whose problems are of his own making, a clear metaphor for the Chinese people as a whole suffering under warlords and foreign imperialists. During the 1911 revolution, Ah Q’s thoughts are all about the revenge that becoming a revolutionary will enable him to take on his enemies:

hina

All the villagers, the whole lousy lot, would kneel down and plead,

Modern C

‘Ah Q, spare us!’ But who would listen to them! The fi rst to die would be Young D and Mr Zhao … I would go straight in and open the cases; silver ingots, foreign coins, foreign calico jackets …

Another famous story,

Diary

of a Madman

, points the fi nger of blame for China’s crisis even more explicitly. The story concerns a young man who goes mad and becomes convinced that his friends and family are cannibals who are trying to eat him. Eventually, he consults a book about ‘Confucian virtue and morality’, only to fi nd that ‘between the lines’, the real text reads ‘eat people’. None too subtly, Lu Xun’s message was that China’s traditional culture was a cannibalistic, destructive monster. These stories, still read by every schoolchild in China today, cemented Lu Xun’s reputation as an anti-Confucian voice for whom the modernization of China could not come too soon. While Lu Xun’s later writing takes a more ambivalent tone towards the past, particularly as China’s 122

present became more intolerable, he never lost his sense of anger that his country had became engulfed in such diffi cult times.

On the other hand, Lu Xun’s writings are less clear about what form a China which rejected its Confucian past should take.

Different visions of modernity are visible in other writers of the time. Mao Dun (1896–1982), the pseudonym of the writer Shen Yanbing, wrote one of the fi nest evocations of urban modernity in

Midnight

(1933), the opening scene of which describes Shanghai as a city lit up by neon, and the harbour of which is dominated by a huge advertisement beaming out the words ‘LIGHT, HEAT, POWER’, seemingly describing not just the product advertised, but the city itself. For anyone who has seen the new Shanghai which has grown up since 1990, this will seem a familiar scene: today’s skyscrapers and neon lights, absent for more than half a

Is C

century after the Communists’ rise to power, would also strike a

hinese c

chord with anyone who knew Mao Dun’s city. Mao Dun’s Shanghai

ulture modern?

was glamorous but ruinous: the protagonists of

Midnight

gamble on the stock market and fi nally lose everything.

A different aspect of modernity informed the work of Ding Ling (1904–1986), the pseudonym of Jiang Bingzhi. Still the most famous woman writer of modern China, Ding Ling made her name with a novella,

The Diary of Miss Sophie

(1927), which discussed in unprecedentedly frank style the sexual longings of a young woman. Even Sophie’s name was a gesture towards a modern internationalism: not a usual name for a Chinese,

‘Sophie’ brought to mind Sofi ya Perovskaya, the Russian anarchist revolutionary who tried to assassinate Tsar Nicholas II. Sophie is deeply dissatisfi ed with her own life, recovering from tuberculosis in Beijing, and is deliberately cruel to her friends to drive them away. Yet she burns with desire for a handsome young man, confi ding to her diary: ‘I can’t control the surges of wild emotion, and I lie on this bed of nails of passion.’ Again, the contradictions expressed by Sophie were symbolic of a wider crisis that affected 123

young, urban women in China: new freedoms were open to them, but how were they to make use of them?

Sophie’s dilemmas, of course, were very much those of the relatively privileged and educated minority dwelling in China’s cities. The plight of the working classes was tackled by another major writer of the era, Lao She (1899–1966), in his novel

Camel

Xiangzi

(translated as

Rickshaw

). The protagonist, Xiangzi (an ironic name that literally means ‘fortunate’) tries to get together enough money for his own rickshaw, but loses it all, along with his fi ancée who is forced into prostitution and dies before he can rescue her. The novel ends with a broken Xiangzi picking up cigarette-ends to eke out a miserable living. Lao She’s portrayal of Xiangzi is far more sympathetic and humane than Lu Xun’s savage caricature of Ah Q. Yet it is clear that Xiangzi, too, is meant to be an ‘everyman’, and by falling victim to ‘individualism’, the term Lao She uses to criticize him, he has contributed to his

hina