Miss Ellerby and the Ferryman (7 page)

Read Miss Ellerby and the Ferryman Online

Authors: Charlotte E. English

Tags: #witch fantasy, #fae fantasy, #fantasy of manners, #faerie romance, #regency fantasy, #regency romance fairy tale

She

was more perplexed when the carriage bowled out of York and into

the fields, leaving the town far behind, yet without delivering her

to any of the villages she had expected they were to visit. Half an

hour’s journey passed away and still they did not stop. Isabel

began to glance at her aunt, uncertain of whether she should raise

a question. Mrs. Grey did not look at her; her attention was

directed out of the window.

Isabel contented

herself with silence. Fully an hour had passed by the time the

carriage at last began to slow, and finally stopped.

‘Quickly, now,’ said Mrs. Grey as they stepped down. She

consulted a pocket-watch, a slight frown creasing her

brow.

Isabel looked around in utter confusion. They had stopped in

the midst of an expanse of fields. Tall rows of flourishing wheat

met her gaze in every direction, with nothing else to be observed

save for the strip of narrow, uneven road running through the

middle. Besides herself, her aunt, and her aunt’s coachman and

footmen, not another soul did she see.

Tafferty jumped down from the carriage behind Isabel and took

up a station near her feet. This surprised Isabel, as she had been

unaware of her companion’s presence upon the journey. Where had

Tafferty hidden herself? She, too, appeared to feel no

disorientation at the peculiarity of their excursion, for she sat

down and began, in the calmest fashion, to wash her

paws.

‘Five

minutes, perhaps?’ murmured Mrs. Grey.

Tafferty made an

assenting noise, and continued to groom her toes.

Isabel began to feel a sensation of mild pique at this

treatment. Was she not to be informed as to the nature of their

errand out here in this remote place? She pushed such feelings

away, for they were unworthy, and stood her ground. Her aunt and

Tafferty were both facing the same way, out into the fields, and

watched the horizon with an expectant air. Isabel could understand

nothing of this behaviour, but she followed the line of their gaze

and waited alongside them, fiddling with the ribbon of her

reticule.

It

seemed to her, after some minutes, that the sky was growing

fractionally lighter. She blinked, and looked a little closer. Was

she, in her impatience, imagining the almost imperceptible fading

of the azure sky into a paler hue? No; for there followed an

unmistakeable brightening of the light, until it grew so dazzling

Isabel was obliged, briefly, to close her eyes.

When

she opened them, a dark shape had appeared in the sky, starkly

outlined against the blazing light. It began as a small object

barely larger than her fist, but grew rapidly. Isabel realised that

it was something airborne, and coming closer.

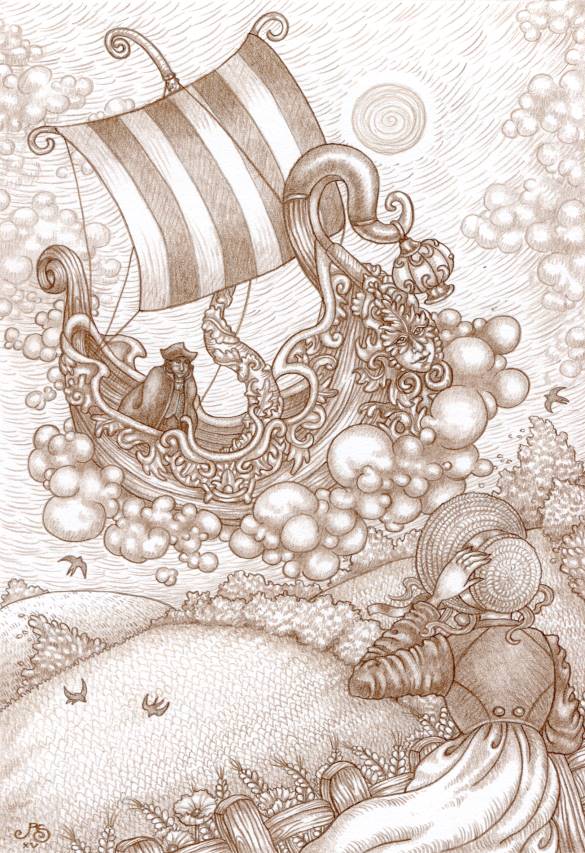

It

was a boat. It was shaped like one, at least, with a mast and a

sail and all the usual features; the fact that it was sailing

through the sky instead of the sea appeared not to matter one whit.

The boat soared out of nothing and descended until it landed atop a

low rise some distance away.

‘Quickly, now!’ said Mrs. Grey, and to Isabel’s amazement, her

aunt began to run.

‘Whishawist!’ bawled Tafferty, and sprang after Mrs.

Grey.

Isabel stood

stock still, dumbfounded.

Tafferty turned and galloped back. ‘Hurry, foolish little

witch! The Ferryman will not wait for such as thee, mark my words!’

She barrelled into Isabel’s legs and propelled her forward. Isabel

dutifully set off at a fast walk, but at Tafferty’s renewed cries

of “Wist, whishawist!’ and the sight of her aunt running at speed

towards the boat, a sense of urgency took hold of her and she, too,

began to run.

If

she had expected the boat to be made out of something familiar —

wood, for example — she was destined to be further surprised. As

she neared the strange craft, she discerned that it shone in odd

colours. The body of the boat was constructed from a substance

resembling wood mingled, in some odd fashion, with clouds; the sail

was bright with colour and looked painted upon the sky. The boat

rose up high in the front and at the back, forming graceful,

curled-over points at each end, and the mast was silvery-pale and

deeply graven with complex images Isabel could not make

out.

In

the prow stood a man Isabel had never before seen. He was tall and

lean, and dressed in the fashions of the previous century: tall

boots, a frock coat and waistcoat, and a cocked hat with three

corners. The style of the clothing was familiar, but its materials

and colours were not. His frock coat was rich blue and sewn from

velvet as soft and plush as moss; his waistcoat was as light as

insect’s wings and glimmered with silvery iridescence.

He

was golden-skinned, bronze-eyed and dark-haired, his features human

but with that faint, odd cast which proclaimed him Other. He was,

in short, Aylir.

Mrs. Grey reached

the boat some way ahead of her niece. Isabel drew level with her

aunt, somewhat out of breath and, she feared, unbecomingly flushed

in the face. She took a moment to regain her breath, averting her

gaze from the dazzling vision of the boatman.

‘You

wish to embark?’ said the Ferryman. His voice was deep and melodic.

He would sing well, Isabel thought irrelevantly.

‘This

lady wishes to embark,’ said Mrs. Grey, gently pushing Isabel

forward.

Alarmed, Isabel cried, ‘No! I do not wish to embark! My dear

aunt, what can be the meaning of this?’

Mrs.

Grey clutched Isabel’s hand. All trace of the playful attitude she

sometimes adopted had vanished; her face, her manner, her tone were

all serious as she said: ‘You have some notion, I think, that you

may live as I have done; choose the life of an Englishwoman and

manage your abilities alongside it. I wish you will not! For I have

long regretted the choice that I made.’

Isabel’s mouth opened in surprise. ‘But — my uncle — were you

not happy?’

Mrs.

Grey’s mouth twisted with some emotion Isabel could not name. ‘I

chose safety,’ she said. ‘If that is the choice you, too, wish to

make, then you shall. But I beg you: please, explore the

alternative! I have arranged everything. The Ferryman will take you

to your Miss Landon, and she will help you.’

‘But—’ said Isabel, shocked. ‘But the assembly — Mr. Thompson

—’

‘Think nothing of them,’ said Mrs. Grey. ‘Assemblies, and such

men as Mr. Thompson, are easily come by!’

‘My

mother—’

‘Your

mother shall know nothing of this,’ said Mrs. Grey earnestly.

‘Trust me to manage my sister, and do as I ask. Please.’

Isabel glanced at the boat and the Aylir man who stood,

silent and impassive, in its prow. A knot of fear had taken root in

her stomach and she felt its effects in every part of her being. To

step into this boat and allow it to bear her away to Aylfenhame

seemed an irreversible step. ‘I cannot,’ she said

softly.

‘You

can,’ said Mrs. Grey with quiet confidence. ‘Tafferty will be with

you. You are not alone.’ She squeezed Isabel’s hand and added, ‘It

is not forever.’

Not

forever. Isabel looked again at the boat, and, to her infinite

surprise, a tiny spark of excitement unfurled somewhere inside. It

was feeble, and almost drowned by the weight of her doubt, her

uncertainty and her fear; but it lived, and she felt it. To see

Aylfenhame as Sophy did! Not as a brief, and wholly other, visitor,

but as one who enjoyed some right to be there; who might, in some

small way, belong.

She

squeezed her aunt’s hand in return. ‘Thank you,’ she said. A vision

of Mr. Thompson at the coming assembly flashed through her mind.

Would he notice her absence? Would it be any source of regret to

him? Perhaps he would withdraw his interest in her. Her mother’s

dismay — her father’s disappointment — the loss to her family. All

this passed through her mind in an instant, and her steps

faltered.

But she looked

again at the Ferryman, and her resolve hardened.

‘I

cannot wait,’ said he. He spoke gravely, but Isabel thought she

detected a twinkle in his dark eyes.

‘I am

coming,’ Isabel replied. He held out his hand to her; she took it,

and with his help climbed aboard the boat. Tafferty leapt in after

her with a flick of her tasselled tail.

She

had no time to bid her aunt farewell, for the boat began

immediately to rise. All she could do was wave to her aunt’s

rapidly shrinking figure as she was borne upwards, conscious of a

forlorn feeling.

Chapter Six

Isabel had expected the ascent to be alarming, perhaps even

dangerous, but it was not. The boat’s progress was steady and

smooth, and though the rising winds buffeted her with growing

ferocity as they climbed into the skies, she never felt in danger

of being blown out of the boat.

The

vision of England she was thus afforded staggered and thrilled her.

Vast expanses of fields lay spread before her, painted in various

colours and fitted edge-to-edge like scraps of fabric in a blanket.

Here and there she saw a village or a town, mere clusters of blocky

protrusions in grey or red or white; they were tiny and toy-like

from her vantage point aloft. At length her view was obscured as

white mist billowed into being around her, thickening rapidly until

she could see nothing beyond the edges of the boat. With a small

sigh of regret, she turned her back upon the vanished panorama and

sought some place where she could seat herself.

The

Ferryman sat three feet away, his eyes upon her. She jumped at

seeing him, for in her wonder at the view she had all but forgotten

him. She swallowed her surprise, smitten abruptly with

remorse.

‘I am

very sorry,’ she said with a smile. ‘I was so enchanted with our

ascent, I have sent courtesy to the winds. How do you do? My aunt

ought, perhaps, to have introduced us, but there was not time. I am

Miss Ellerby.’ She made him a curtsey. He ought to have stood to

receive this honour, and it felt strange to her to curtsey to a

seated gentleman. But things were different in Aylfenhame, no

doubt.

The

Ferryman’s answering smile was crooked; twisted, she suspected,

with some form of hidden amusement, though the expression of his

eyes was congenial enough. ‘Missellerby,’ he mused. ‘No name I ever

heard before. ‘Tis a privilege to be unique, and I hope ye make

fine use of it.’ He got to his feet and bowed fluidly to her in

return, sweeping his three-cornered hat from his head. She saw that

his hair was black and long, and tied back with a plain red ribbon.

He soon regained his seat, and indicated that she should avail

herself of one opposite. They were chairs in truth, soft and

comfortable, and upholstered in a shimmering silk Isabel eyed with

covetous envy, so beautiful a gown would it make.

She

reposed herself gracefully upon the indicated chair, and smiled.

‘No indeed, I am not at all unique. It is two words: Miss — Ellerby

— the first being a title, you see.’

His

smile widened, and the twinkle in his eyes grew more pronounced. ‘I

thank ye for yer explanation,’ he said gravely.

Isabel laughed, her cheeks warming. ‘Oh, I see. You are

teasing me.’

‘An’

I should not, I know,’ he said with a note of apology. ‘It’s the

matter o’ having company that’s done the mischief. Goes to my ‘ead

more’n a little.’

His

manner of speaking reminded Isabel of Balligumph, the

bridge-keeper, though his accent was neither so thick nor so

pronounced as his; more of a lilt. ‘Are you so short of company?’

said she. ‘I would think a Ferryman would meet a great many

people.’

‘The

Ferry,’ he said, ‘is not often used, for few seek passage between

my world an’ yours.’

Isabel felt a creeping sensation of discomfort, for it did

not do to be alone with a gentleman like this. Did Tafferty qualify

as chaperone? Her companion had taken up a station on one of the

other chairs, and sat there straight-backed and wholly inattentive.

Isabel looked down at her hands. ‘I did not precisely seek

passage,’ she admitted.

‘I

saw that.’ The Ferryman lounged against the side of the boat, idly

flipping his hat in his hands.

Isabel flushed with embarrassment. ‘My aunt had given me no

warning,’ she said. ‘It was not discussed between us.’