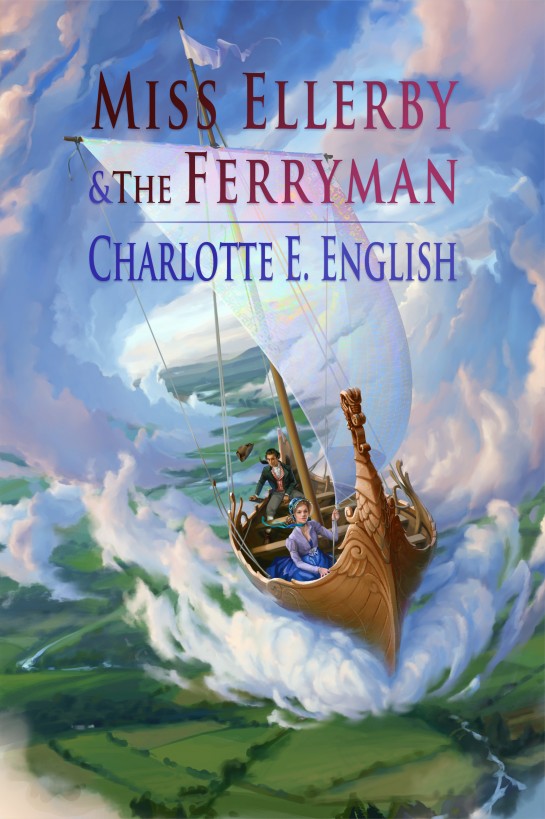

Miss Ellerby and the Ferryman

Read Miss Ellerby and the Ferryman Online

Authors: Charlotte E. English

Tags: #witch fantasy, #fae fantasy, #fantasy of manners, #faerie romance, #regency fantasy, #regency romance fairy tale

Miss

Ellerby and the Ferryman

(Tales of

Aylfenhame, 2)

by

Charlotte E.

English

Smashwords

Edition

Copyright 2015 by

Charlotte E. English

Cover design

copyright 2015 by Elsa Kroese

Illustrations

copyright 2015 by Rosie Lauren Smith

All rights

reserved.

This ebook is

licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be

re-sold.

***

Now,

halt just a moment if ye’d be so kind! There’s a toll to pay, if ye

wish to pass over the Tilby bridge, an’ I’m the toll-keeper.

Balligumph’s my name! I may be a troll but I'll not be hurtin' ye.

No, I’ll not ask ye to step out o’ yer fine carriage, but yer

coachman won’t do. I need a toll from ye. Nowt o’ any particular

importance, mind. Just a bit of information. Yer name, an’ yer

business in Tilby; that’ll do. An’ one little tidbit o’ somethin’

else — somethin’ secret-like. That’ll do nicely. An’ on ye

go!

Or,

no! Stay a while. I fancy I’ve heard yer name before. Maybe I’m

mistaken — I’m no young troll, ye may notice, an’ I sometimes

forget things. Remind me. Was it yer good self to whom I told the

tale o’ Miss Sophy Landon an’ her husband, Aubranael? It’s tales I

like. I like to hear ‘em, an’ I like to tell ‘em. Ye’ll remember,

perhaps, about Miss Sophy, an’ what a fix she was in. No home, no

money, an’ no one to look after her! But she’s well an’ settled in

Grenlowe now — that bein’ a town in Aylfenhame, ye’ll recall — an’

mighty happy she is.

But

she’s not the only young lady o’ Tilby to get ‘erself entangled wi’

the faerie realm. She ‘as a friend, Miss Isabel — oh, she’s one o’

the kindest young ladies in these parts, no doubt o’ that! Perhaps

ye’d like t’ hear her story? It’s a jolly tale, for all tha’ she

came to — well, no, I’ll no give away the ending! Come, sit wi’ me

a while an’ I’ll start from the beginnin’!

Chapter One

‘Isabel, my love, do come and look! The shoe-roses have

arrived. Now, these will do very well with your lavender gown, do

you not think?’

Mrs.

Ellerby’s voice, penetrating in its enthusiasm, carried easily over

the sounds made by the Ellerby household brownie as she vigorously

swept the parlour hearth. Isabel’s mother chattered on, holding up

handfuls of ribbons, shoe roses and other trifles for her

daughter’s perusal and approval. With an inward sigh, Isabel set

aside her needlework, and went to the parlour table.

‘They

are beautiful, Mama,’ she said in a mild tone, ‘but I had thought

we had decided upon my gown for tomorrow? Is it not to be the

blue?’

Mrs

Ellerby nodded absently, her attention fixed, apparently

irrevocably, on the ribbons in her hands. ‘It is what we agreed

upon, but think, my love, how much the lavender becomes you! It is

the very thing to go with your hair. If you had been light-haired I

should not venture to recommend it, for it can be a trifle insipid!

But with your colouring I should think it the very thing!’ Mrs

Ellerby continued on in this style for some time while her daughter

listened dutifully, playing about with a piece of gold ribbon which

had fallen from the box.

In

due course came the inevitable. ‘And I am persuaded, you know, that

it is the very thing which Mr. Thompson would like.’

‘Mama,’ said Isabel gently, ‘we must not allow Mr. Thompson’s

supposed preferences to rule us entirely. I should prefer the

blue.’

‘Yes,

yes, I am sure you are right.’ Mrs. Ellerby paused, and bent her

attention to a fresh pair of shoe-roses she had at that moment

pulled from the box.

Isabel

waited.

‘But

I am persuaded you might reconsider, if only you were to think

—’

‘Mama! Please! It is decided: I shall wear the blue.’ Isabel

dropped her ribbon and stood up. ‘It is time for my walk, now that

the rain has cleared. Please, put the shoe-roses away.’

Mrs. Ellerby

subsided with only one more faint protest, and Isabel made her

escape.

It

was early in July, and the morning was warm. Isabel regretted the

bonnet and spencer jacket that propriety insisted she should wear,

though the former was of straw and the latter of the lightest

sarsenet. A breeze ruffled her dark brown locks as she turned in

the direction of Tilton Wood, and for a wistful moment she

considered removing her bonnet entirely, and tucking it under her

arm. After all, there was no one to see her.

But

no, it would not do. A passerby may happen upon her at any moment,

and even were it but a farmer, Miss Ellerby of Ferndeane must not

be seen to commit so great an impropriety as to wander the fields

of Tilby without a hat. Her Mama would be appalled.

Resigned, Isabel heaved a great sigh and walked on, turning

into Tilton Wood with relief. The great oak trees offered cooling

shade, and the sunlight filtered through the green, green leaves

cast pleasing dapples over the earthen floor. Isabel slowed her

pace to a stroll, and her tumbling thoughts slowed to match

it.

Mr.

Thompson was the son of an old friend of her Mama’s — at least,

Mrs. Ellerby chose to claim Mrs. Thompson as a friend. In truth,

they had merely been at school together, and Isabel could not find

out that they had ever been close. But her schoolfellow had married

well. The Thompsons were a family of consequence, settled some

fifteen or twenty miles south of York, and Mr. Thompson was, as

yet, unmarried.

By

some means beyond Isabel’s comprehension, her mother had

re-established contact with Mrs. Thompson, coaxed her into renewing

their acquaintance and had at last persuaded her to attend an

assembly in Lincolnshire — with her son. That assembly was due to

take place tomorrow night, hence all Mrs. Ellerby’s anxious

preparations today.

Nothing had been said to Isabel in so many words, but she

understood that she was to be offered to the young man as an

eligible bride. Her family was not wealthy, but they were

respectably endowed with a genteel fortune, and Isabel could expect

to inherit some twelve thousand pounds someday. Mama hoped that

this, together with Isabel’s person, manners and accomplishments,

might be sufficient to tempt the young man.

Isabel’s own feelings upon the matter were undecided. She had

long known that she was expected to raise the credit and position

of her family through her marriage, and now that her brother

Charles had engaged himself to Miss Jane Ellis — a very pleasant,

unobjectionable girl, but one who brought neither money nor

connection to her marriage — the obligation had fallen more heavily

upon Isabel herself. She had rejected the advances of Mr. Reed,

Tilby’s new parson, not long since. He was neither rich enough nor

important enough to satisfy her parents, and he had not been

congenial enough to satisfy her. But having failed to accept one

proposal of marriage, her parents were beginning to grow anxious

that she should soon receive another.

She

was ready to perform her duty, and willing to be directed by her

parents if it must be so. Their ambitions were not such as to lead

them to bestow her upon anyone unworthy, or to give her in marriage

to anyone she had taken in dislike. But she felt all the pressure

of their hopes and expectations keenly, and she knew very well that

Mama especially had set her heart upon Isabel’s liking Mr. Thompson

well enough to marry him.

Of

course, since his marriage with Isabel would bring him little by

way of connection or standing and only a moderate fortune, it fell

upon her to try to capture his heart. This she was not at all

certain she was equal to. Mrs. Ellerby sensed this, and had tried

to make up for Isabel’s reluctance with a fever of preparation over

her dress, hair and ornaments. If Mr. Thompson did not instantly

fall in love with her daughter’s beauty, it would not be for lack

of trying.

These

reflections weighed heavily upon Isabel’s mind as she strolled and

sighed through Tilton Wood, paying only the barest attention to the

route she took. Her abstraction was such that she wandered deeper

into the wilder parts than she would normally choose to do, and

soon began to feel that she had lost her way.

She

walked about for some minutes, attempting with all of her natural

good sense to calm the flutter of worry which began to intrude upon

her peace. But it would not do. She could not convince herself that

she recognised any of the several winding pathways which presented

themselves to her searching gaze, and the flutter of alarm grew.

Tilton Wood was not known for being especially expansive, but it

was fully large enough to detain her some hours should she lose her

way. Severe would be Mama’s alarm should she fail to reappear

within an hour.

Schooling herself

to calmness, she paused to consider that walking about aimlessly

was as likely to render her situation worse, as to bring about any

solution. She stopped instead, reposed herself upon a great branch

which had fallen nearby, and applied herself to the question of how

best to extricate herself from her predicament.

She

had not been about this for more than a few moments before it

occurred to her that the cluster of leaves at which she had been

vacantly staring was not a cluster of leaves at all, but something

living. Its limbs were as slender and gnarled as twigs, its head a

shade too large for its body, and it sported a great pot-belly

which strained against the ragged leaf-brown dress it wore. The

creature’s nose was as knotted as a whorl of wood, its ears long

and twisted, its eyes bright, azure blue — and fixed upon

her.

Isabel started, but before she could speak a word, the

creature said in a high, lisping voice, ‘Goodest of mornings to

you, Mistress! What is your bidding?’ She — for Isabel felt, by

some instinct, that the creature was female — bowed low as she

spoke, and offered Isabel a tiny violet flower.

Isabel opened her

mouth; found, in her surprise, that she had nothing to say; and

closed it again.

‘Mistress?’ prompted the little fae creature, staring fixedly

up into Isabel’s face.

‘I

think there must be some mistake,’ said Isabel. ‘I am not your

mistress! Indeed, I do not think we have ever before

met.’

‘This

is our first meeting,’ agreed the fae, ‘but without doubt, my

mistress you are! For did you not summon me?’

‘I

assure you, I did not!’ cried Isabel. ‘I do not know how I could

have done so! I am sorry, if you have been put to any

trouble.’

The

fae creature considered this in silence, her tiny lips pursed.

‘Then you are not lost?’ she said at last.

‘I am

lost,’ Isabel admitted. ‘But I feel sure I shall find my way at any

moment; pray do not be put to any trouble on my

account.’

‘It

is that way,’ said the fae, pointing out the direction with a

finger as thin and delicate as a new shoot.

Isabel glanced in the direction indicated. A pathway opened

up through the thick undergrowth, clear and inviting. It was odd,

but in beholding it now, it was perfectly evident that therein lay

her route home.

Isabel came to her feet and shook out her skirt. ‘Thank you,’

she said, and curtseyed.

The little fae

bobbed an ungainly curtsey in response and smiled with sunny

enthusiasm, revealing a mouthful of green teeth.

‘I am

Tiltager,’ she offered. ‘This is my wood.’ With that, she vanished.

Isabel found herself staring at a cluster of leaves which so nearly

resembled Tiltager, she wondered whether she had imagined the

whole.

No;

she had not. She paused a moment in indecision. Should she trust

Tiltager? Fae were a common enough sight in England, but while some

of them devoted themselves to aiding their human counterparts and

sometimes formed the deepest friendships, others were equally

dedicated to causing harm. Tiltager’s path may not lead back to

Tilby at all, but to somewhere else entirely; somewhere Isabel

could have no wish to go.

But

the little fae had seemed friendly. Nothing in her behaviour or her

manner had led Isabel to suppose that she intended any harm. Isabel

began walking in the direction Tiltager had indicated, tentatively

at first and then with growing confidence as the pathway soon took

on proportions that were familiar to her. It even seemed, as she

walked, that the tranquil oaks sped by a little faster than was

entirely reasonable, and she found herself restored to the

outskirts of Tilby sooner than she had imagined

possible.