Minerva's Voyage (5 page)

Scratcher, meanwhile, was instructing Proule on what he wanted done with the notes. Boors thanked me and I grinned. Though it was now clear as glass that Scratcher was the boss in this enterprise, I needed to be in the good books of both of them. And Proule too, if I didn't want to find myself in the bottom of the sea with pearls for eyes. He was scary. Mary mattered less than the shit pail in the hold. When we reached land I would be done with her. Or so I thought.

Two days later, the wind was blowing strong but friendly, pushing us along quite handily. The storm hadn't materialized. I had heard Piggsley say we would reach Virginia within the fortnight, and so no longer feared every moment that we would soon all be drowned dead. But I still felt greenish, as Fence would have put it.

“You s'll soon get your sea legs, lad,” Piggsley assured me, every time he saw me.

I was waiting for them to be delivered.

Scratcher was ignoring me today. He was scratching his leg and his threepenny bits. I'd faded into the woodwork, in a manner of speaking, into the timbers of the ship, too familiar or contemptible to be taken into account. At least, he and Proule were talking as if I wasn't there, and that was fine with me. I still had to bend forward to hear them, though. The racket below hatches was appalling. It seemed to grow louder with each passing day. People arguing, children skriking, and beasts, those that weren't yet eaten, lowing or squawking for all they were worth. The din, together with the heat, was even getting to Proule and Scratcher.

“We sail too far south, man,” complained Proule. “We'll never get where we're going this way.”

“Not so,” replied Scratcher, looking dangerous. He stopped scratching and stroked his knife hilt.

“The other ships is burning up with fever. I couldn't get away fast enough when I delivered them letters from Boors. I was afeard for my life and health.” Proule was sitting on a hogshead of ale and picking at what remained of his teeth with a large splinter.

“There's no helping it.” Scratcher countered.

“The wind blew fair for a while, but now we're tacking in the wrong direction.”

“We have to go south, you dithering numbskull, or we'll be blown all the way back to England. But it is to our advantage. Let the simpletons on the other ships think we'll come up the coast to Virginia after we've crossed.”

“Don't yer call me a numbskull.” Proule wiped the splinter on his jerkin, leaving a long smear.

“No, Proule, my fine handsome fellow, you're quite right. I forgot myself. I'm too used to speaking to that jelly-livered drudge over there.” He pointed in my direction. “But all we need is a spot of rain and lightning and we'll look like we're making for the Baruadas, as stipulated on those letters you delivered. In truth we'll make for the Isle of Devils.”

Proule hiccupped.

“I know what I'm doing. I've been much employed, had jobs in high places,” confided Scratcher, who had been drinking gallons more ale since our water had gone stale, and was talking too freely, as usual.

“And yer've been thrown out of most of 'em, as I've heard.” Proule, too, had been tippling, but unlike me, he hadn't learned when to hold his yap.

Scratcher bent down and thrust his face into Proule's, eyes popping. “Who told you that?” A few men turned to stare at him before going on with their business, such as it was.

“I dunno.”

“Piggsley, I'll be bound, with his loose lips.” Scratcher toyed with his knife again.

“No, Master Thatcher. 'Tweren't him.” Proule drew back. “Sorry, sir. I got beyond myself. It's the drink in me talking.”

“Watch your mouth in future or I'll watch it for you.”

“Aye, sir, Master Thatcher.”

Scratcher pushed him off the hogshead and sat on it himself. “I'm the most important person in this dungeon of a hold. Boors wants me for secretary in Virginia â or wherever.” He waved his skinny hand in the air.

“That's good news,” muttered Proule, staggering up and trying to look agreeable, a rather difficult task given his features. His face finally rearranged itself into a horrid grimace beneath his bald pate, his tombstone teeth on display. I couldn't blame him for trying though. Eventually everyone knuckled under to Scratcher. He could be fierce and frightening as a corcodillo, and corcodillos ate men and boys whole, didn't they? Or so Oldham had warned me when I wouldn't recite my Latin.

“I play along,” said Scratcher. “But I mean to make my fortune. Don't want to work for any man but myself anymore.”

“And so say all of us, every man jack of us. Amen.” Proule sat down on the dirty floor and took a long draught of ale. Scratcher drank also, his legs splayed so wide he almost fell backwards off the hogshead. They both hiccupped. It was time for me to find out more. While they were both so drunk they'd sleep like the dead. With Fence as my lookout, I would go scavenging this night. I crossed myself for luck.

C

HAPTER 8

H

ORRIBLE

P

ROULE THE

G

HOUL

Midnight at least. Hot as an oven. Quiet, except for Scratcher's snores, which shook our part of the hold. Fence lit a stub of a candle he'd brought from Boor's cabin. His face haloed in the dark. I put my hands on the chest, felt around for the secret knob, and pressed. The lid sprang open.

“Move the candle over here,” I hissed. “I can't see.”

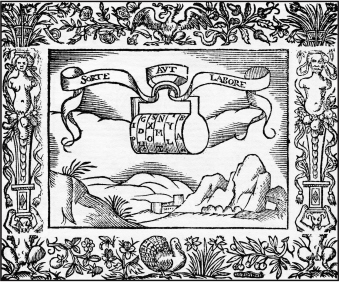

Fence sniffed, scrunching up his nose, and lifted the candle. The circle of dim light moved from his face to the contents of the chest, and I started to rummage through them. An emblem. Another emblem, neither of them the ship in the storm, which Scratcher must still have about him. And finally, a third emblem.

“Look at that!” I whistled.

“Shh. What is it?” whispered Fence. “I've never seen anything like it before.”

“It's a cipher wheel. Right there on that emblem. It's used to decipher secret messages. And it's telling us there's a hidden message

here

that we have to decipher. I'm sure of it.”

“Take it out.”

“No. I'm only going to look, and maybe take one small thing so Scratcher doesn't notice. If we take a wad of papers, he'll smoke us out right away. Besides⦔

“There's only so much you can hide under a holey shirt and threadbare jerkin,” said Fence.

“True it is.”

Fence was not such a dunce, after all.

I went back to the chest and riffled under the three emblems. All that was beneath them was a mysterious piece of vellum. I stared at it. The alphabet was on the left in sepa

rate columns, with a different arrangement of x's and y's by each letter.

“What's that?” asked Fence, sniffing again.

“I'm not sure. But it's important as hell or my name's not Robin Starveling,” said I, examining it. “Hold the candle closer.”

A xxxxx G xxyyx N xyyxx T yxxyx

B xxxxy H xxyyy O xyyxy U/V yxxyy

C xxxyx I/J xyxxx P xyyyx W yxyxx

D xxxyy K xyxxy Q xyyyy X yxyxy

E xxyxx L xyxyx R yxxxx Y yxyxx

F xxyxy M xyxyy S yxxxy Z yxyyy

It wasn't very clear despite the light cast by the candle, but I kept looking at the vellum till the x's squiggled up and down and began to jig. What could it all mean?

Scratcher's snores ceased, and he moaned. He was waking up! My heart clip-clopped. I inched the chest shut, but still kept ahold of the vellum. Fence pinched the wick of his candle. After a sickening silence that seemed to last till doomsday, Scratcher's breath caught and he began to snore again.

“This way,” I whispered. We crawled on hands and knees over bundles and boots, until we reached the ladder beneath the hatch. It was still slung open to draw in fresh salty air, such air, that is, as would consent to brave the fug and travel down to the colonists.

My purpose was to climb up to the deck, sick though it would make me to see a seascape unanchored to land. I would be able to view the vellum more clearly up there. But before I shinned the ladder, a cloud above passed, and the man in the moon peered in upon us, making it light enough to see. I started to examine the x's and y's again, Fence getting in the way more often than not. For a small boy, he certainly had an incredibly big head, and he kept thrusting it in front of mine to get a better look at the sheet of dancing and mysterious letters.

“Move your bonce,” I said, annoyed.

Just then, fingers grasped my shoulder hard, nails digging into my skin like grappling hooks. “Get off,” I yelled.

My cries disturbed the dreams of one or two travellers, whose pale faces stared at me for a moment, before their owners blinked and fell back to sleep.

A growl. The sickening stench of farts and tomcats and sour wine, stronger than all the other stinks of the hold. As the nails dug even deeper into my shoulder, I imagined blood spurting from crescent-shaped wounds.

“Give over. You're killing me.”

“Shut yer yap, cockroach.”

I turned, though I already knew who it was: Proule, that coffin-mouthed ruffian. My belly heaved.

At that moment the

Valentine

's prow churned out of the water, hurling me into him. He shoved me backwards, punched me, and before I could recover, tore the vellum from my hand. and before I could recover, tore the vellum from my hand.

“What the ruddy hell is this?” He flapped the vellum. The moon shone in. His bald head reflected it.

I could taste blood. My belly heaved again. What could it be that wouldn't incriminate us? That wouldn't send Proule howling to Scratcher? I couldn't think of a damn thing.

“I said, cockroach, what the hell is this?”

Fence had slipped as the ship nosed out of the sea. He came crawling slowly on all fours, his head down.

“Please, Master Proule⦔

“What?”

“It's a list of my duties from the admiral, Sir George Winters, good Master Proule.” He began, baby-like, to suck the tip of his thumb.

At this point I noticed Proule was holding the vellum upside down. Could he even read? I decided to chance it. Taking my cue from quick thinker Fence, I said, “All those things on the left, they're the days of the week, enough for a month. Next to them are the duties. Sweep the deck; take Sir Thomas Boors his dinner; empty the piss pail and shit buckets overboard.” I had seen Fence perform such-like duties before.

“Why would the likes of yer be reading it in the middle of the ruddy night?”

“He forgot a duty, sir, yesterday, the dinner one, and got in trouble with Sir Thomas Boors.” I felt sure that if asked, Boors wouldn't remember one way or the other. “We were figuring out where Fence went wrong â he's not much of a reader, and I'm a worse one, sir, true it is. Why, some days I can barely read at all.”

“Aye, sir.” Fence's head came up, and his thumb came out, his expression earnest. “We were figuring it out so I wouldn't make the same mistake again and come in for a good thrashing.”

Proule looked from Fence to me and back again. Then he squinted at the page, one eye shut, turning it sideways and over and right side up. No question about it. He didn't trust us, but he couldn't read. The rogue was flummoxed.

Fence stood up. “It's mine! As I told you, it's from the admiral. And if you don't give it back, I'll tell him you've stole it from me.”

“Yer shan't if yer know what's good for yer.”

“I'll do it, sir. I will.” God be praised. That boy had real guts.

Proule flinched, then thrust his head forward. He opened his mangy mouth wide as a corcodillo basking in the sun. For a moment I was afraid he was going to snap his rotting fangs shut on Fence's nose. But, “Yers, is it, yer cheeky dog? Don't yer be wasting my time again, y'hear me? I'm an important man with important doings.”

He ground the vellum into his palm, screwed it up, then tossed it away. As he ran up the ladder, taking his rancid reek with him, I crept over to retrieve the crumpled sheet. I smoothed it and stuck it in my shirt, relief flooding my veins. I had a sudden thought and took it out again, holding it beneath the open hatch. The moon illuminated the script for a moment, disappearing as the ship lurched and we tacked southwest into the dark night. But I'd had enough time to check my theory. I'd been right. What I had here was a cipher key. A real one, sure enough. Though as to what it was supposed to

de

-cipher, and how I or anyone else was supposed to decipher it, I had not a single clue.