Minerva's Voyage (2 page)

“Careful, boy. Stop daydreaming. There's treasure inside,” Scratcher scolded now. I turned my attention back from Oldham's fat gizzard to his fat chest. His chest of the wooden, not the fleshly sort, I hasten to add. His fleshly chest looked more like a mine that had misfortunately suf

fered a cave-in.

“I haven't so much as touched the chest yet, sir.” But my pulse twitched a couple of times. Spanish dollars were already glittering, big and round as silver plates, in my imagination. Treasure, was it? Scratcher could prove really valuable to me. My eyes must have lit up like can

dles on Sunday.

“Not that kind of treasure, you ignoramus. Intellectual gold. Poems and maps.” His knotty face slanted sideways, and his loose neck skin creased into a wattle.

“Oh,” said I, trying to ignore the fact that he looked like a demented cockerel and concentrate instead on his words. I'd spent two years in school trying to avoid poems and maps. But though I say so myself, I was sharp as a rapier, and much learning had rubbed off on me. What kind of poems and maps might these be? They were certainly not like those in the writing and cosmography lessons given by old dry-as-dead-bones Oldham. They would be treasure maps. With an X marking the spot. Ho ho. A shard of excitement flew up my arms, piercing my heart.

“Are you coming or not, sirrah? The hour is at hand.” Scratcher managed to sound pompous and religious at the same time.

“What hour is that, sir?”

“You'll find out soon enough.”

I chewed on the inside of my cheek loudly. I gestured into the northwest wind. But everything was performance, with him as spectator, because my mind was already made up. I had nowhere else to go, and there was also that treasureful mystery that had just cut deep into my heart and now tickled my brain. He cuffed me on the head. I jerked the chest skyward. He jumped back in momentary alarm, and I laughed in my mind. Then he nodded, turned, and veered along the cobblestone alley. I followed.

C

HAPTER 2

R

OBIN

S

TARVELING:

A

P

LAYFUL

N

AME

The hour was the hour of sailing. Unbeknown to me, I had been carrying a sea chest. If I'd have realized that the idiot was going to sea, I'd never have budged from my begging corner. I was terrified of the ocean. I was even scared witless of wells, would throw a rat hellwards to hear the dark splash. But I'd never look over the rim for fear of drowning. I'd seen others drown in the past, not in wells but with their ship almost to shore, their arms thrust above the waves, their voices thick yet shrill. Later there had been no voices, just the roar of the ocean and the nearby snarl of breakers. That was worse than the screams. Just like the silenced howls of hanged thieves and murderers, when they swung back and forth in the wind: The sound of no one. Yet here I was on a boat, the

Valentine

, as we rocked away from the dock. I'd tried to bolt at the last minute, treasure notwithstanding, almshouse notwithstanding. But Scratcher, as I came to know him, had tripped me up, shouldered his chest for once, and dragged me aboard by the hair, confirming with his treatment of me my already dubious impression of his nature.

Fearfully, I looked to the sea. We were in the company of other boats, their rigging tight as sinews, their sails slung out like women's petticoats. I counted six ships and two smaller pinnaces, all stuffed with souls. We were no different. Our own deck was as busy as the Bear Gardens at Candlemas.

“Bound for Virginia,” an important-looking man shouted.

There was a ragged hoorah from the crowd, but a few travellers, men and women after my own heart, looked white as Monday's washing.

“Let me off. I don't want to go,” I yelped.

“Don't worry. That's Sir George Winters, our admiral,” said a dark-haired boy, pointing to the important-looking man. The boy was slightly smaller and probably younger than me. He wore an old black glove on his right hand, for reasons unknown, and sounded proud. “The admiral's a good seaman. He'll take care of us. But don't get on the wrong side of him.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I'll remember not to.”

Winters didn't appear too frightening, not compared to some I'd come up against in the past, but I was terrified in a more general way anyhow. Virginia was the other side of the great ocean. The trip could take months. Maybe, despite what the dark-haired boy said, we'd fall off the edge of the world on the way. Or go down with our arms flung up, like the drowned sailors. I hadn't spent my time avoiding hang

ing so I could plummet to the bottom of the ocean.

“Virginia?” I asked Scratcher, still not really believing.

He didn't respond. He was busy scratching his arm, his face to the wind, his graying hair wisping out behind him.

“Chin up, Ginger Top,” said a sailor, who was swabbing the deck. He smiled crookedly and rested his arm on one of several cannons. It was huge, snub-nosed, and black, and gave me not a whit of confidence. Were we to fight pirates, then? Or the vessels of the Spanish Main of which, even as a landlubber, I had heard too much?

“There's a name for you, sirrah. Master Ginger Top.” Scratcher grinned, then spat through a hole in his teeth into the huge expanse of water beside us.

“Not likely, sir.” Carrots was bad enough, and I'd heard that too many times to count.

He thought for a moment. “Starveling, then. Robin Starveling. You do look pared down to the bone, and that's a fact.”

I frowned. Who was he to talk? He was skinny as a hun

gry rat. His hands had the scrawny look of hens' feet. But Starveling was as good a name as any, I supposed, though Heaven knows where he'd dragged it from.

“There was one called that in a play,” Scratcher said, as if in answer to my thoughts, “when I was working in the theatre. He was just about as dim and as thin as you are.”

Well then. Affronted I might be, but there was no way, after all, that I'd trust my real name, which was now buried in my brain, to Scratcher. He'd ridicule it for sure. Besides, the less he knew the better. Meanwhile, the more I found out about him the happier I'd be. Robin Starveling, eh? It had a ring to it.

I looked at the cannon again, fear rising in my throat.

“No need to be afeard, boy, of the sea. We s'll all make our fortunes.”

“They say that the trees are high as mountains and the river by Jamestown wide as an ocean,” whispered the dark-haired boy. He turned suddenly and clambered up the rigging. I kept my eyes down, too dizzy to look up. He disappeared from my view in a twinkling.

“Aye. An' the streets is paved with gold and the shores awash with diamonds and rubies. Ain't that so, Master Scratcher?” The sailor winked.

“Don't be stupid, Piggsley. There are no streets. And no jewelled sands. And the name, as you very well know, is Thatcher.”

“Aye aye, sir.” Piggsley tipped his threadbare cap.

Scratcher was now watching an ample-hipped woman in a red skirt as she swayed across the deck. When she disappeared below, he licked his thumb, dabbed mud off his hose, and slid slick as an eel through the hatch. “I must speak to her about the sumptuary laws,” he said, halfway through. “Poor woman that she is, she has no right to be dressed in scarlet.”

“That's Mary Finney,” obliged Piggsley. “She does ser

vices for gentlemen.”

“Does she indeed?” Scratcher grinned.

“Laundry services, I meant.” But Scratcher was gone. Piggsley screwed his finger around his ear thoughtfully. “There's Will Scratcher, er, Thatcher, for you,” he said. “We calls him Scratcher cause he's always scratching sundry parts of himself. Jes' now it was his belly. Other times he ain't so polite.” Winking at me, Piggsley went on, “A single whiff of woman and he's away. Then he says it's his great sin. I seen him on other voyages.”

So Scratcher had a weakness for women, did he? And Scratcher had also been on other voyages. I tucked these tidbits into the back of my brain in case I should have need of them. Then I upchucked my last meager meal of bread and wiped my mouth free of sick.

“Steady there, lad. We's barely out of port.” Piggsley fin

ished sweeping our part of the deck and moved on.

Sea travel didn't bode well for me. I felt better for being empty, though my mouth tasted bitter as aloe and the dizziness remained. And the blasted chest still needed to go down to the hold. No one would shift it except me, and I must have walked it damn near five miles this day, in and around Plymouth. I would best Scratcher for taking me to sea, I swore silently. And for making me carry his vile heavy chest crammed with maps and poems all around the town. It might take five days. It might take fifty. But I would best him.

C

HAPTER 3

I

N THE

B

ELLY OF THE

B

OAT

We were sailing southerly and somewhat westerly. Or so Piggsley had told me. It was hot as hellfire below and stank of mold and filth and foot-rotted boots. The smell would surely choke us by the time July arrived, that's

if

we were still alive then.

“Hello again.” The dark-haired boy I'd seen on deck was speaking to me. The heat didn't seem to inconvenience him. “Who are you?”

“Robin Starveling.” I carefully parcelled out my words so as not to sound too friendly. Besides, though they too stank, I had boots and he had none. It placed me a notch up in the world.

“Peter Fence,” he returned. “I'm the cabin boy.”

As if I wanted to know. “I'm the servant of Master Will Thatcher.” I threw my shoulders back to show my importance. Uncomfortable in that position, they soon slumped forward again.

“Scratcher's servant? You look right greenish and that's a fact. But redheads often do, even on land, and besides, you'll get your sea legs soon enough, never fear.

“I'm employed by Admiral Winters.” He held his hand out, the one with the glove, and I shook it. But I kept my nose in the air as I did so, to one-up him a little and let him know I didn't usually shake hands with cabin boys â not even the cabin boy of an admiral. I was making a special exception for him.

“Pleased to make your acquaintance,” I said. “Why do you wear that glove?”

He ignored the question. “I have to report to Admiral Winters.” He saluted with his ungloved hand and raced up the ladder, two rungs at a time.

A few moments later, Scratcher lurched out of his hammock, buttoning his jerkin with one hand while scratching his private bits through his hose with the other. “Shake a leg,” he told the heap of red that had been lying next to him.

It was Mary.

A couple of sailors nudged each other and whispered something as she strolled away, picking up her stockings and shoes as she went. “I bin doin' his washing,” she said. She winked.

“Stop smirking, Starveling.”

“I'm not smirking, Master Thatcher. I'm imagining.”

“Stop imagining, then. I don't pay you to imagine.”

“Hell's Bells and little fishes. You don't pay me at all, sir.” I felt this needed to be said.

Scratcher ignored me. His eyes were glassy as he stared after Mary, and no wonder. They'd been entertaining each other for hours. The hammock had jiggled most fearfully. I'd hoped it would collapse, but was unlucky. Maybe tomorrow, if he entertained her again.

“Stop rubbing yourself and get your bony backside off my coffer. I need to find something.”

“Important, is it, Master Thatcher?”

“Important? Everything of mine is important. Can you read, you little weasel?”

“No, sir. Not the smallest squiggle. I haven't been taught,” I lied. My tongue explored a painful hole in my tooth. Pain was an apt punishment for falsehoods. Or so that bitch Oldham always said when she whipped me.

“Your talk is amazingly genteel for an illiterate.”

“Nevertheless, sir, I cannot read. Not even my own name. I expect that's why I forgot it. My mother was a gentle

woman, I believe, but she disappeared too soon to teach me.”

“Ah. So you're an ever speaker but a never writer.”

“I would be more than willing to learn sir.”

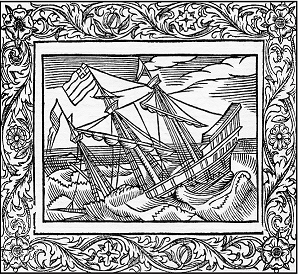

“Never mind. You suit me better as you are.” He threw open the chest. “Take hold of this.” He slid me a sheet of paper with a picture of a three-masted ship on it. It looked like the

Valentine

in a storm, God save us. Underneath the ship was a poem. I struggled to read in the dimness, but the poem was written in a hand that was somewhat hard to make out. Scratcher snapped shut the chest and yanked the sheet from my fingers.