Microbrewed Adventures (26 page)

QUITO ABBEY ALE

â1534

Taking the proportions of malt, sugar and hops as revealed in the 1966 recipe, I've formulated a small-batch recipe that closely matches the character of beer brewed in the final and 432nd year at the monastery. This recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

T

HE ELECTRICITY

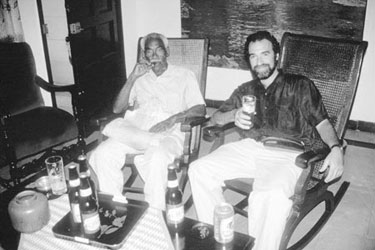

and lights are out in my neighborhood, Charlie, but not to worry. There is no problem.” No problemâyes, the universal phrase spoken in every language, taking on infinite degrees of unreality. We found ourselves winding our way through the streets of Havana, ending in a western suburb. One street block was electrified; another was night dark. We stopped, and the noise of his Russian-built automobile slowly gave way to the vibrancy of the tree-lined neighborhood. The engine pinged as it cooled. I slowly rolled up my window and sat bewildered in the front seat, noting the sounds of the neighborhood, breathing the tropical night air. A hum of conversation filled the air, yet no one could be seen. It was darkâvery dark.

Then I noticed the open-air porches above me on the second story of each home. The orange glow of a lit cigar slowly swayed in a silent and languid arc.

In his rocking chair an old man bided time, as most Cubans are apt to do in these difficult times of “austerity.” Then I realized the night air was filled with dozens of these tiny orange, swaying, arcing embers. The embracing aroma of Cuban tobacco deliciously filled the evening. Laughing, crying, teasing, joking and serious conversation seemed to gently abide in every household visible and invisible.

We walked through a gate and into a secretly lit, small but comfortable home to have one of my first beer tastings in Cuba. But as I left those moments behind, I knew I would never forget them. They so typified my impressions of today's Cuba: mysterious, intriguing, friendly, incredibly complex and a country constantly on the verge of anxiety.

I was 13 years old in 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis. I can recall listening to my younger brother's six-transistor Sony pocket radio (a new invention at the time) in the darkness of our bedroom, wondering if the world were about to end. That was my first and lasting memory of Cuba. Now, with this educational and journalistic trip hosted by the Cuban government I was on my way, in search of the lost beers of Cuba. I knew that beer was being brewed in Cuba, but little else. In my pre-trip research through commercial literature and in conversations with international brewing colleagues, I was surprised to discover that there was virtually no outside knowledge of the Cuban beer market and brewing industry. Curious, I wanted to find out what very few knew. Months of preparation and attempts at organizing this trip proved mostly futile, but as I was determined I went unconfirmed, assuming the most but expecting the least. Through a series of personal and diplomatic contacts I was unofficially told that the Cuban government and the Minister of Food would officially host me as a journalist. Embarkation day arrived with nothing certain, except my determination.

I boarded an airliner in the tropical heat. I certainly could have used a beer, but only rum was offered. Cool air cascaded from overhead vents into the cabin. As it collided with the humid air, a cold, moist cloud mystically layered the aisle a foot deep. I was in the clouds before we took off. I must admit to a few fleeting moments of panicâ“Where am I going? Where am I? Am I crazy?” These were real-time thoughts. My heart pounded with the anxiety of the unknown as we headed toward Havana. The clouds swirled both inside and outside the cabin at takeoff. I was on my uncertain way. But as I always realize, anxiety is a very highly overrated experience. Forgive me; I did not have a homebrew with me.

Approaching legendary Havana, I looked down with some trepidation. From high above and among the billowy clouds we glided past dozens of base

ball diamonds and deep blue swimming pools languishing in the stillness below. “There has to be beer down there somewhereâ¦there just has to,” I thought to myself. And with beer there are always fine people.

As I disembarked the plane I was met on the tarmac by a translator and the Ministerio de la Industria Alimenticia (Minister of Food). My bags, passport, visa and transport were being cared for through the diplomatic lounge as I was offered a rum mojita and introduced to the possibilities for the next few days: the breweries of Havana and the surrounding area, a flight to the eastern post-revolutionary city and brewery of Holguin, a road trip to Cerveceria Camagüey and a return by air to Havana for an opportunity to give a presentation to the marketing, operations and brewery managers of Havana.

Given several options, I chose to make the most of my visit and accepted an offer by my Cuban government hosts of a full itinerary. From this point on, for five days and six nights I immersed myself in the culture and leisure of Cuba. But beer is my business, and I was working overtime.

What little I had read and heard about Cuba before the trip proved to be quite inaccurate. I must admit that I developed a great admiration for the people of Cuba after seeing and touring the existing facilities, listening to the government's assessment of existing conditions and future efforts, freely roaming the streets and seeing and talking with the local people. Yet both during and after my visit, Cuba remained an enigma. What was really going on there? The issues were complex. The opinions were passionate. I left no

more certain about Cuba's beer culture and brewing industry, though I know that it truly exists and remains to be explored. Discovering the soul takes time.

Soon I began to shatter the myths of my imagination, but not without a flood of long-forgotten memories of people, places, cars, food and feelings of what it was like for me, growing up in the 1950s and early 1960s. In a time warp, the cars, the music, the spectacularly beautiful art deco Spanish-American architecture of the 1950s are still much intact. But sadly, there is more crumbling and disrepair. Old Havana is the historic port of the early 1500s as well as a favorite haunt of Ernest Hemingway. I enjoyed a daiquiri where it was invented and a mojito (rum, lime, sugar, ice and mint) at the bar where it was first concocted. Although I was not visiting Cuba as a tourist, my hosts easily found cold beer for my enjoyment. The quality was variable but mostly acceptable.

Cuba's potential for economic development is quite staggering. In 1959 more than 2 million American tourists came to Cuba, many for gambling and an experience of decadence. After the revolution, the government nationalized all industry and property. Gambling fled and later emerged in Las Vegas. Many Cuban businesses and individuals lost fortunes; many who left still hate the existing regime, vowing someday to return and recover their lost property. But this will be difficult for the brewing companies, for at this point

there is little left to recover but the earth on which these fading breweries barely exist.

Havana brewers

On the road, one of every 10 or 15 cars is a 1951â1954 Chevy, Oldsmobile, Plymouth, Packard, Cadillac, Ford or Pontiac. They are truly a breathtaking sight to behold and one of the real and unique tourist “resources” in Cuba. Cubans have kept them running for 40 years with haywire and bubblegum. Carburetors are reconstructed from tin cans if necessary. It would be a crime to see them sold and leave the island to languish in the garage of a car collector. In Cuba these are real cars used by real people. They certainly are proud. Though they have little, it doesn't show in their physical appearance. They are a determined and hard-working people. And they make things work, inside or outside the system. The same is true of the brewing industry. They have developed some incredibly creative ways to remain operational.

During my visit the streets were spotlessly cleanâthere was no trash to discard.

Stagnation has characterized the brewing industry for the past 35 years. The state “owns” and manages all seven brewing factories. Similar products are produced by more than one brewery and often under different formulations. The lack of capital and materials has drastically affected the manufacture and quality of the products. Almost all of the beer is brewed with 50 percent sugar, few bottles are labeled (labels are in scarce supply) and work

ing equipment is continually being cannibalized to provide spare parts for downsized operations.

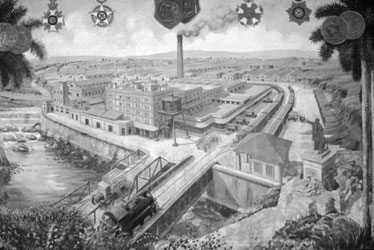

Early 20th-century Havana brewery

Miraculously, the brewers of Cuba continue to brew beer with equipment that by industry standards would be virtually unacceptable elsewhere. But I noted one exception at the post-revolution brewery in Holguin, which was fitted with East German brewery equipment and a canning line. The spirit of the brewers and operations people was inquisitive and searching for many answers during my visits, tours and seminars. Their persistence produced the best product possible under difficult circumstances and was a testament to the league of brewers everywhere and the tenacity of the Cuban people.

Cuba's brewing heritage is proudly evident in the spectacularly grandiose outdoor tropical beer garden at Havana's Tropical Brewery and on display at the brewery museum. There, in a corner of the museum, remain likely the only artifacts of Cuba's best-kept beer secrets: bottles and labels of past Vienna lagers, bock beer, Munich dark and crystal (malt) lagers. They are there as a quiet testament, day and night, year after year, hardly noted by the inside world and noted not at all by the outside world. Seeing is feeling, and one knows immediately that Cuba had a rich brewing heritage in years past. What were these beers? I can only imagine. My hosts knew little about these lagers, yet hinted that there may still be some old-timers on the island with long memories.

Yes, there is beer in Cuba. Tropical, Polar, Tinima, Mayabe, Modelo and Hatuey light lagers can be found easily with American dollars and with difficulty otherwise. They are brewed with pride by brewers who know very little about the international brewing community. Their desire for quality and improvement qualifies them for acceptance into this community.

VIENNA-STYLE OURO DE HABANERA (HAVANA GOLD)

I imagine a great beer and have thirsted for something other than a characterless light lager. I dreamed: What if I were asked to brew a beer for a Cuban microbrewery? What might it be? This is my answer: a German-influenced full-malt-flavored golden lager with added corn to freshen up the body and increase drinkability. Hop flavor and character are essential. This recipe can be found in About the Recipes.

The brewery personnel were eager to learn of the beer industry beyond their borders. They noted that my visit to Cuba was the very first contact Cubans had had with the American brewing industry in 35 years.

I am fascinated by the possibility that someday once again bock, Vienna-and Munich-style lagers could be reintroduced to a land where beer is no stranger. But for now, if you yearn for a Cuban lager you would be more satisfied wistfully enjoying rum poured over ice, crushed mint leaves, lime juice and sugar.