Methods of Persuasion: How to Use Psychology to Influence Human Behavior (22 page)

Read Methods of Persuasion: How to Use Psychology to Influence Human Behavior Online

Authors: Nick Kolenda

Tags: #human behavior, #psychology, #marketing, #influence, #self help, #consumer behavior, #advertising, #persuasion

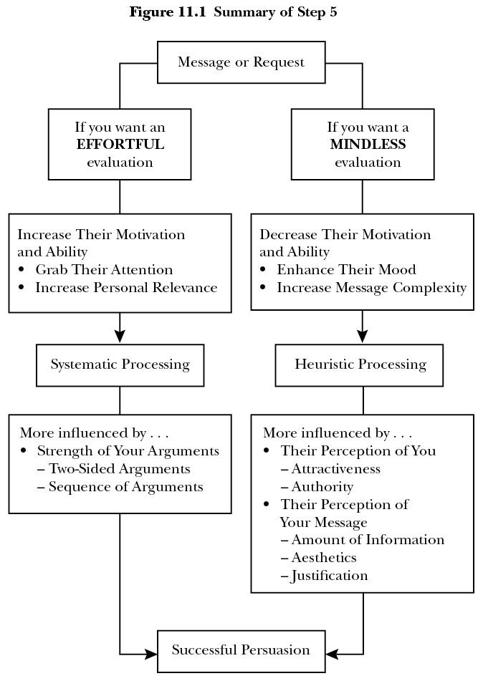

I realize that there was a lot of information in this step of METHODS, so I made a diagram to summarize this step. You can refer to Figure 11.1 on the following page.

REAL WORLD APPLICATION: HOW TO IMPRESS YOUR BOSS

As you prepare to leave work one day, your boss approaches your desk with a request: she asks you to prepare and deliver a PowerPoint presentation at 11:00 a.m. the following day. Although you’re dead tired, you prepare a few slides and then leave. You plan to finish the rest of the slides the following morning before you present it.

That night, you set your alarm clock for 5:00 a.m. so that you can wake up early to finish the presentation. However, to your dismay, your alarm clock fails to work, and you wake up the following morning at 10:00 a.m. You rush to get ready, but you arrive to work late at 10:30 a.m.

You would need at least two hours to prepare a quality presentation, but you only have a half hour available. In order to determine the best focus of your time for that half hour, you casually stop by your boss’s office to gauge her mood. To your surprise, she’s in a rather pleasant mood, and she asks you how the presentation is coming along. Despite the panicking thoughts inside your head, you give her a resounding, “It’s coming along great!”

Armed with the knowledge of her mood, you rush back to your desk and begin working hastily on the presentation. Because your boss’s mood is pleasant, and because you studied the concepts in this book, you realize that your boss will be less critical of the actual underlying arguments in the presentation (i.e., she’ll be relying heavily on heuristic processing). She’ll also be influenced by other factors that are irrelevant to the actual arguments, such as the aesthetics of the presentation. Therefore, rather than try to create stronger support for the information that you put in the presentation the evening before, you decide to focus on enhancing the aesthetics of the presentation. You spend the next 20 minutes enhancing the color scheme, layout, and overall appearance of the PowerPoint slides. You’re hoping that your boss’s pleasant mood will lead her to view your aesthetically pleasing presentation and assume that the underlying content is equally as strong.

The time is now 10:50 a.m., and you have 10 minutes remaining before you must guide your boss through the presentation. At this point, you spend those remaining 10 minutes brainstorming clever and articulate ways to phrase the information that you’ve already compiled. Due to her reliance on heuristic processing, you should be able to convince your boss that the underlying arguments are strong if you can deliver them in an expressive and confident manner.

Ten minutes pass, and you go to your boss’s office to guide her through the presentation. To your delight, your boss congratulates you on a stunning job, with additional compliments on the layout of the presentation. You end by letting your boss know that you’d be happy to investigate the topic further so that you can deliver a presentation with even stronger supporting evidence. She agrees, and you walk out of her office with a sigh of relief.

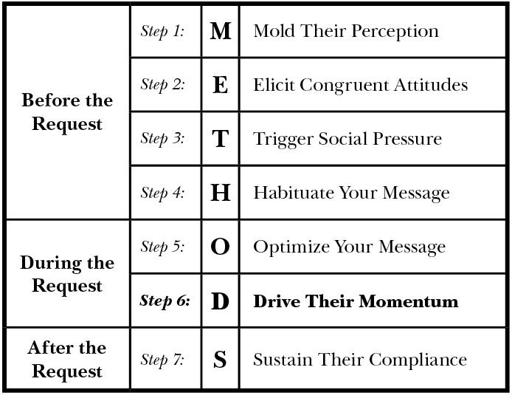

STEP 6

Drive Their Momentum

OVERVIEW: DRIVE THEIR MOMENTUM

Although you’ve now presented your request, you’re not done yet. Rather than throw your request on the table and pray that your target complies, why not use a few psychological tactics to spark some more motivation?

The chapters within this step will explain two powerful techniques to further drive your target’s momentum toward compliance. First, you’ll learn how to give your target proper incentives (it’s not as straightforward as it might seem). Second, you’ll learn how to harness the power of limitations and “psychological reactance” to exert even more pressure. After implementing these tactics, you should receive their compliance (but if not, the final step in METHODS will help you out).

CHAPTER 12

Provide Proper Incentives

I rarely watch TV, but one night I was flipping through the channels when I stumbled upon an episode of the

Big Bang Theory

, an episode where Sheldon, the eccentric braniac main character, was trying to influence the behavior of Penny, the female main character. Much like dog trainers reward their dogs with a treat after they perform a desired behavior, Sheldon offered Penny a chocolate each time that she performed a good deed (e.g., cleaned up his dirty dishes).

Although Sheldon’s “positive reinforcement” successfully changed Penny’s behavior throughout the course of the episode, could small rewards shape our behavior in real life? Though an amusing portrayal, that underlying psychological principle—

operant conditioning

—is actually very powerful. When used properly, rewards and incentives can nonconsciously guide people’s behavior toward your intended goal.

But what’s considered a “proper” incentive? As you’ll learn in this chapter, many people make a few surprising errors when they use incentives to reward and motivate people. This chapter will teach you how to avoid those common mistakes so that you can offer incentives that will be successful at driving your target’s momentum.

THE POWER OF REWARDS

It all started in the 1930s with B. F. Skinner, the most well-known behavioral psychologist. He created what came to be known as a “Skinner box,” a box that automatically rewarded a rat or pigeon each time they performed a desired behavior. After observing how those rewards caused his animals to express the corresponding behavior more often, he proposed his theory of operant conditioning to explain that behavior is guided by consequences; we tend to perform behavior that gets reinforced, and we tend to avoid behavior that gets punished (Skinner, 1938).

How powerful is reinforcement? One night, Skinner set the reward mechanism in several Skinner boxes to give pigeons a reward at predetermined time intervals. Even though the rewards were only based on time (i.e., not the pigeons’ behavior), the pigeons nevertheless attributed those rewards to whichever behavior they were exuding immediately before those rewards. As Skinner described, their misattribution led to some peculiar behavior:

One bird was conditioned to turn counter-clockwise about the cage, making two or three turns between reinforcements. Another repeatedly thrust its head into one of the upper corners of the cage. A third developed a “tossing” response, as if placing its head beneath an invisible bar and lifting it repeatedly. Two birds developed a pendulum motion of the head and body, in which the head was extended forward and swung from right to left with a sharp movement followed by a somewhat slower return. (Skinner, 1948)

You might find those behaviors somewhat amusing, but we’re not that different from pigeons. Many of us actually perform similar behavior without realizing it.

Do you ever wonder why superstitions are so powerful? Why do so many of us perform a lucky ritual each time that we perform a certain action? For example, you might dribble a basketball three times—no more, no less—every time you shoot a foul shot because you think it brings you good luck. Are you insane? Nope. You were simply guided by the same forces that guide pigeons.

You can start to see the connection when you consider how that basketball ritual might have emerged in the first place. Suppose that you just made a foul shot after bouncing the ball three times. You jokingly attribute your success to bouncing the ball three times, and in your half-joking manner, you decide to bounce the ball three times for your next shot. And . . .

Swish

. Whaddya know, you make your shot again.

From this point forward, you start to gain more belief in that ritual, and so you perform it more often. Now that you’re starting to develop the expectation that your ritual helps you make foul shots, you’re more likely to trigger a placebo effect and actually make your shots more often when you perform that ritual. More importantly, your belief in that ritual will now perpetuate because it will continuously be reinforced through your increasingly successful foul shots. Much like a pigeon will perform odd behavior because it misattributes a reward to that specific behavior, you’ll start to perform your arbitrary ritual more often because you will misattribute your successful shots to that ritual. See, we’re not so different from pigeons.

PERSUASION STRATEGY: PROVIDE PROPER INCENTIVES

This chapter breaks tradition by skipping the “why rewards are so powerful” section (the reason is explained in the final chapter). The rest of this chapter will focus on the practical applications of using incentives to reward and motivate your target.

First, offering any type of incentive will boost your persuasion, right? Wrong. Mounting research has disconfirmed the common dogma that all incentives lead to better performance. The main reason for that surprising discrepancy can be found in two types of motivation that result from different incentives:

- Intrinsic motivation

—Motivation that emerges from a genuine personal desire (i.e., people perform a task because they find it interesting or enjoyable) - Extrinsic motivation

—Motivation that emerges for external reasons (i.e., people perform a task to receive a corresponding reward)

Because intrinsic motivation is generally more effective, this section will explain the types of incentives that extract intrinsic motivation from your target.

Size of Incentive.

Common sense dictates that large incentives are more effective than small incentives. Intuitively, it makes sense; but that’s not necessarily the case. Extensive research shows that small incentives can be more effective than large incentives in certain situations.

Perhaps the most direct reason why large incentives can be ineffective is that they sometimes increase anxiety levels. When people in one study were given incentives to perform tasks that measured creativity, memory, and motor skills, their performance sharply decreased when the incentive was very large because it caused them to “choke under pressure” (Ariely et al., 2009).

Does that mean that all large incentives are bad? Not at all. When incentives aren’t so large as to increase anxiety levels, they

can

elicit higher levels of motivation and compliance. Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini (2000a) conducted an experiment that attracted considerable attention from academia because of their surprising finding. They gathered a group of high school students to travel from house to house collecting donations, and they offered the students one of three different incentives:

- Large incentive (10 percent of the total money that they collected)

- Small incentive (1 percent of the total money that they collected)

- No incentive (just the same good ol’ heartfelt speech about the importance of the donations)

Among those three incentives, which do you think elicited the most motivation from the students (in terms of the amount of money collected)?

Believe it or not, the students who received no incentive collected the most money (an average of NIS 239 collected). Students who received the large incentive were a close second (an average of NIS 219 collected), followed by the students who received the small incentive (a pathetic average of NIS 154). This surprising finding led the researchers to conclude that you should either “pay enough or don’t pay at all.”