Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece (42 page)

Read Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece Online

Authors: Donald Kagan,Gregory F. Viggiano

Often the shield was covered by a very thin bronze sheathing (

chalkōma

), which afforded extra protection against the wood splintering, and helped dissipate the force of blows over a larger area.

12

Even in its current state, the Bomarzo shield offers an excellent example of both the thinness of the bronze facing and the remarkable concavity of hoplite shields: “The bronze cover, which is about 0.5 mm thick, forms a shallow bowl about 10 cm deep and between 81.5 cm and 82 cm in diameter, including a rim which projects about 4.5 cm from the wall of the bowl all round.”

13

Nevertheless, many vase images of hoplite shields suggest that shield concavity was frequently even more pronounced. The inner surface of the shield was usually padded with a glued-on layer of leather, which was likely mounted in order to decrease wear and tear

on the wooden core, and to prevent the wood snagging or pinching the bearer’s arm. By Henry Blyth’s estimate, however, the leather layer inside the Bomarzo shield is too thin to have afforded any real protection from penetration, and is therefore chiefly decorative.

14

The bronze shield facing was apparently optional, but whether the shield had one or not, the shield rim (

itys

) was invariably reinforced with a bronze band to protect the vulnerable edges. The

itys

was thin enough to be wrapped around the shield edge itself, and there is at least one case of an

itys

covering the shield rim halfway.

15

This reinforcement was indispensable on any hoplite shield, and the reason is obvious: if the edge were insufficiently protected, it would be very vulnerable in combat. The joints of the laths would be open to blows, especially lateral sword cuts, which could separate the laths from each other and thus cause the shield to disintegrate.

Emil Kunze and Hans Schleif ‘s listings of the numerous hoplite shields dedicated at the sanctuary in Olympia show diameters between extremes of 80 cm and 100 cm (most between 90 and 100 cm); and the famous Spartan shield captured at Pylos in 425, somewhat bent out of shape, measures 95 × 83 cm. Interestingly, Rieth mentions a shield that is in other respects similar to the one examined, but which measures no less than 125 cm in diameter.

16

The large diameter gave the shield a considerable surface area: between 6,362 and 7,853 cm

2

, according as the diameter was 90 or 100 cm.

17

That hoplite shields were of a considerable size seems also to be borne out by a passage in Arrian’s

Anabasis

. Here, the garrison of Miletos, consisting of Milesians and mercenaries, panicked and abandoned their positions when the city was stormed by Alexander’s invading Macedonian troops in 334:

Then some of the Milesians and the mercenaries, attacked on all sides by the Macedonians, threw themselves into the sea. On their own inverted shields, they then paddled across to a small, nameless island near the city. Others boarded small vessels and hurried to get past the Macedonian triremes but were caught by them at the harbour entrance. The majority, however, perished in the city itself.

18

The word

aspis

in itself of course does not necessarily betoken a

hoplite

shield; but the fact that the shields are inverted (ὑπτίων) for the purpose of flotation seems to corroborate this. If these were hoplite shields, they naturally had a wooden core; but what provided the buoyancy in this case was rather the principle of displacement. It is reasonable to assume that the soldiers in this case, as so often, had discarded most of their weapons and equipment, and so weighed considerably less. However, when Alexander turned his attention to the three hundred survivors after taking Miletos itself, he realized that they were ready to fight to the death (διακινδυνέυειν), a fact that prompted him to spare their lives. This seems to indicate that they may after all have kept their offensive weapons as well. Whether the soldiers kept their weapons or not, we should probably estimate that each shield-boat in this situation had to keep some 60–70 kg afloat on average.

19

If these events actually took place as described by Arrian, a considerable displacement (and, consequently, shield surface area) was therefore necessary. Let us look

at the physics involved. The density of the shield in question is extremely difficult to ascertain, since the amount of metal in addition to the wood is unknown, but it may be assumed that the overall density is less than 1. The density of saltwater is slightly higher than that of freshwater: a 5 percent saltwater solution has a density of 1.034, which is probably not too different from seawater. It is difficult to say with any exactitude without precise knowledge of the concentration of salt, however, so water density will not be factored in. At any rate, the actual buoyancy would not have been less than the result of the calculation. Apart from the shield’s own buoyancy, the amount of air contained within the shield produces a buoyancy equal to the amount of water it displaces without the shield edges submerging. Therefore, if the shield contains 10 l of air, it can displace 10 l of water, weighing 10 kg, before becoming submerged and sinking.

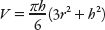

Now, the volume of the relevant geometrical figure, a spherical cap, is determined as follows:

, in which

r

is the radius of the base of the cap and

h

is the height (or depth) of the cap. This yields, for shields of the following dimensions, the volumes shown in

table 8-1

.

Apart from the shield’s own buoyancy and the possibly increased density of the seawater in question, the shield will float approximately the same amount in kg as the amount of liters of air contained. It may be seen, moreover, that small changes in height and radius yield rather greater volumes. It is reasonable to surmise that the hoplites in question had jettisoned anything but perhaps their spears and swords; and assuming an average body weight between 62 and 65 kg for an adult male,

20

it is apparent that the dimensions of the Bomarzo shield are insufficient for it to float a man. It is also evident, however, that the carrying capacity greatly increases with slight increments in dimensions; and on this assumption it does not seem unrealistic for the Milesian garrison to have paddled to safety on their shields.

21

Blyth, in his assessment of the Bomarzo shield, estimates the total weight of all its components at 6.2 kg.

22

Of this, the weight of grips, straps, and fittings is assessed at some 0.7 kg, the rest consisting of the wooden core and the bronze sheathing. The weight of the original wood and bronze can of course be no more than an educated guess, because the materials have decayed considerably over the centuries; but considering that the average hoplite shield had a diameter of 90 cm, rather than only 82 cm as in this case, the combined weight of bronze and wood would have been closer to 6.75 kg. Rieth, in his examination of the Bomarzo shield, reckons with a very pronounced decay of the wooden components and consequently a rather greater mass in the original shield. If we follow Rieth’s assessments, then, we arrive at a shield even heavier than any derived from Blyth’s estimates, weighing as much as 7 or 8 kg. And this still only allows for one layer of wood in the construction of the shield core.

23

That this weight is probably closer to the norm is brought out by the fact that the shriveled remains

alone

of the Basle hoplite shield, as examined by David Cahn, weigh as much as 2.95 kg—or nearly half of the estimated full weight of a “new” and intact Bomarzo shield by Blyth’s estimates.

24

TABLE 8-1

| Shield radius | Height | Volume |

| 45 cm | 10 cm | 32.3 l |

| 45 cm | 20 cm | 67.9 l |

| 50 cm | 20 cm | 82.7 l |

| 45 cm | 25 cm | 87.7 l |

| 50 cm | 25 cm | 106.3 l |

Using the Hoplite Shield

It seems a straightforward enough assumption that the shape and sheer size of such shields would have had consequences for the men bearing them in combat, but the worst problem with the hoplite shield would no doubt have been the considerable weight. On closer inspection, the sources also seem to bear this out.

It is interesting, for example, that merely being ordered to stand still while holding the shield (τὴν ἀσπίδα ἔχων) was considered a sufficient disciplinary punishment in the Spartan army,

25

which was not otherwise known for being particularly squeamish when it came to maintaining discipline by means of corporeal punishment.

26

The element of physical ordeal in this type of punishment has been downplayed,

27

apparently because Xenophon, in whose

Hellenika

the punishment is mentioned, adds “[which] is regarded by distinguished Spartans as a great disgrace,” almost by way of an afterthought.

28

There can be no doubt that

kēlis

certainly does mean “blemish” or “disgrace”;

29

but its mention here does not mean that the disgrace visited upon military miscreants was not intended to be a harsh physical punishment as well. This interpretation is in fact borne out by a comparison with Plutarch’s

Aristeides

, where the Spartan king Pausanias’ harsh treatment of recalcitrant Spartan allies is discussed: “The commanders of the allies always met with angry harshness at the hands of Pausanias, and the common men he punished with lashings, or by compelling them to stand all day long with an iron anchor on their shoulders.”

30

Now, if the punishment that involved standing while holding a shield was merely symbolic (a symbolic value which, one suspects, may not have been immediately appreciable to outsiders), then this case—similar in all respects except for the object actually held—becomes baffiingly pointless. The point was hardly lost, however, on those unfortunate allies who fell afoul of Pausanias and were forced to stand around holding iron anchors all day—even if they were otherwise unaware that this was a particularly shameful brand of dishonor in the Spartan army. The substitute punishment of flogging emphasizes this to an even greater degree: Plutarch evidently sees the anchor punishment as completely parallel to the floggings, the physical nature of which can hardly be denied. Standing τὴν ἀσπίδα ἔχων may very well have been humiliating

or dishonorable for the offender (if he was a Spartan, at least), but it is evident that it was also a grueling physical ordeal. Xenophon’s remark that it was a

kēlis

for the Spartans should be seen in this light: the physical harshness of such a punishment was obvious to any contemporary reader; that it was also considered disgraceful in Sparta was what needed an explanatory remark.

31

An amusing passage in Xenophon’s

Anabasis

points to the same conclusion. During Xenophon’s learning period as commander of the Greek rearguard on the retreat from Artaxerxes’ pursuing Persians, a detachment of hoplites commanded by Xenophon (himself on horseback) “race” Persian troops for possession of a hill commanding the only way forward. One of the hoplites, a certain Soteridas of Sikyon, reacts unfavorably to the

strategos

’ ill-timed pep talk: “It’s not fair, Xenophon! You are sitting on your horse while I’m wearing myself completely out with carrying this shield.”

32

Xenophon, tacitly acknowledging his leadership blunder, jumps down, takes Soteridas’ shield from him, and tries to keep up. He is soon completely exhausted, since he’s also wearing a heavy cavalry

thōrax

; and the other hoplites therefore bully Soteridas to take back his shield. Whether the anecdote is true or not, it must have been acceptable to contemporary readers, so the vignette demonstrates the hoplite shield’s very real problem of sheer weight.

The

Hellenika

and

Anabasis

passages afford a glimpse of how the burden of the hoplite shield was perceived, despite the fact that—or perhaps precisely

because

—the question of weight in either statement is treated in a rather offhand fashion, as is natural with allusions to everyday experiences. Yet other essential characteristics of the shield would also have contributed to making it difficult to use in actual combat. The ungainly shape and the sheer size of the shield made a significant contribution to a quite exceptional awkwardness in handling. As we saw above, the shield’s mass was spread fairly evenly over a surface area of approximately 6,400 cm

2

at a minimum, but could easily reach an area of as much as 7,800 cm

2

. Now, the greater its surface area, the more inertia and thus difficulty in handling any physical object; and one that is the size of a small bridge table is thoroughly unwieldy, no matter how it is held.