Meditations on Middle-Earth (16 page)

Read Meditations on Middle-Earth Online

Authors: Karen Haber

Tags: #Fantasy Literature, #Irish, #Middle Earth (Imaginary Place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Welsh, #Fantasy Fiction, #History and Criticism, #General, #American, #Books & Reading, #Scottish, #European, #English, #Literary Criticism

TOLKIEN

AFTER ALL

THESE

YEARS

DOUGLAS A. ANDERSON

T

olkien has long been an enigma to the critics, but not so to general readers. Sales figures are imprecise, but it was recently estimated that Tolkien’s most popular work, The Lord of the Rings, has sold over fifty million copies worldwide in nearly thirty languages. And a number of polls in recent years have proclaimed The Lord of the Rings to be the book of the century. Personally, I find such polls and declarations to have little real meaning, but a simple truth does emerge that is undeniable, and that is that The Lord of the Rings is a novel much loved by a very large number of readers.

I first read

The Hobbit

and The Lord of the Rings in the summer of 1973, when I was thirteen years old. I was visiting my older sister, and pestering her in the usual ways in which younger brothers excel. I was also bored, and after looking over her bookcase and complaining that there was nothing to read, she stomped in from the kitchen, grabbed the Tolkien books from the bookshelf, and thrust them at me with a few staccato commands: “Here. Read these. You’ll like them. Now leave me alone.”

The books were those Ballantine paperback editions with the surreal Barbara Remington covers, showing a brightly colored landscape replete with emus, squiggly reptilian things, and trees with bulbous fruits. I looked at the books skeptically (as I still view those covers), but in my desperation I thought I’d try them. And I spent the next few days completely engrossed in those four books. Little did I then realize that I would spend the next thirty years studying those books, Tolkien’s life, and his other writings.

My interests that have developed from reading Tolkien have shifted in many ways over these years. At first, I delighted in details of his world of Middle-earth, in the depth of the invented history and in the hints of partially told stories in the appendices. In high school, I wrote a play based on

The Hobbit

, which I performed with a number of my friends. And around that time I also began to read much more widely, both in the literature that inspired Tolkien (from

Beowulf

, the

Eddas

and the Icelandic Sagas, to the prose romances of William Morris), and in the modern writers, who were themselves in turn inspired by Tolkien.

At college I studied more seriously the medieval literatures in which Tolkien had specialized, and I even attended a summer program in Oxford, where Tolkien had lived and taught for much of his life. Through college and in the years that have followed, I have pursued whatever threads of scholarship that have interested me, many inspired by Tolkien, others not. This kind of freedom in my studies (possible only outside a prescribed curriculum) has led me down an unpredictable trail of study in the realms of mythology, fairy stories, and children’s literature, followed by textual studies, bibliography, methods of printing, book production and publishing history, and many other areas beyond what is usually called literature and literary criticism.

I do not think my experience is atypical. Certainly it is not so among many of my Tolkienist friends and colleagues, for I believe that those of us who study Tolkien, and read his work very closely, find that his subtleties, his searching and penetrating intelligence, inspire our own interests to branch out in many unexpected directions. Of course, this observation is very much against the grain of the supposed truth that the critics of Tolkien have long proclaimed—that Tolkien fans read nothing but Tolkien, over and over.

To analyze the critical reception of Tolkien’s works, one must first explain how much the bibliography of Tolkien’s writings has greatly expanded since his death in 1973 at the age of eighty-one. During his lifetime, and for the moment excepting his academic work, Tolkien’s primary literary publications amounted to only a small shelf of books:

The Hobbit

(1937); his short tale

Farmer Giles of Ham

(1949); the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955); the slim verse collection

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

(1962); another slim volume, containing one story and an essay, entitled

Tree and Leaf

(1964); the short stand-alone fantasy story

Smith of Wootton Major

(1967); a song-cycle of Tolkien’s poems set to music by Donald Swann,

The Road Goes Ever On

(1967); and an American paperback omnibus of some of these items called

The Tolkien Reader

(1965). Of all these titles,

The Hobbit

and The Lord of the Rings stand out as the major works, in size as well as in popularity.

Since Tolkien’s death, an extraordinary amount of his previously unpublished writings have appeared, some finished, others unfinished. Very few writers have ever had their literary remains published to this extent, and presented with such exacting care as has been lavished upon these writings. Again temporarily excepting his academic work, since Tolkien’s death we have been privileged to read some additional completed works for children, including

Mr. Bliss

(1982), and

Roverandom

(1998), both of which were illustrated by the author. Another volume,

The Father Christmas Letters

(1976; an expanded edition, retitled

Letters from Father Christmas

, appeared in 1999), reproduces in facsimile the stories and drawings Tolkien, in the guise of Father Christmas, made for his own children each year as they were growing up. In these letters Tolkien ingeniously developed an imaginary history for Father Christmas and the other denizens of the North Pole.

Despite the charms that each of the above books possesses, they remain lesser works when compared with Tolkien’s greater achievement in his wide-ranging creation of Middle-earth; and it is in this latter area where Tolkien’s posthumous publications are really so remarkable. Most of these volumes have been edited by Tolkien’s third son, Christopher, who is almost uniquely qualified to oversee as literary executor the posthumous publication of his father’s various writings, having the same literary background as his father and having a lifelong devotion to his father’s writings. Christopher was a member of the original audience for whom

The Hobbit

was written, and he served as the first critic for his father as chapters of The Lord of the Rings were being written, some of which were sent serially to Christopher in South Africa where he was training to be a R.A.F. pilot during World War II. Christopher also followed his father academically, specializing in the same medieval languages and literatures. And like his father he taught these subjects at Oxford University.

The first major publication was

The Silmarillion

in 1977, an editorially constructed version of Tolkien’s “Silmarillion” legends. (Here I follow the convention in Tolkien scholarship in referring to the published volume in italics, as

The Silmarillion

, while the “Silmarillion” in quotations marks refers to the evolving legends more generally.) This was followed by a collection of

Unfinished Tales

in 1980. From 1983 through 1996, Tolkien fans were given a new collection of Middle-earth writings nearly every year, the sum total being twelve large volumes of Christopher Tolkien’s series on The History of Middle-earth. The resulting fourteen volumes—for one must include

Unfinished Tales

and

The Silmarillion

as part of the whole History—span nearly sixty years of Tolkien’s creative work on his invented world. These volumes contain a multitude of fascinating things—a few completed, though most are not—varying in form from stories, essays, and annals to grammars, maps, illustrations, and poems (short ones, as well as long narrative poems in rhyming couplets or in alliterative verse). These works will be discussed below, but for now, suffice it to say that these fourteen posthumously published volumes contain roughly four times the amount of writing that is to be found in

The Hobbit

and The Lord of the Rings. Admittedly there is duplication and repetition, as well as some overlapping of contents (particularly in the volumes of the History, which cover the writing of The Lord of the Rings); nevertheless the simple amount of material on Middle-earth that Tolkien produced in his lifetime is staggering.

A few additional posthumous publications are worth noting here.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien

(1981) is an enormously significant compilation in the field of Tolkien studies, for Tolkien’s letter-writing style is in itself very engaging, and the letters (often written to fans, answering specific questions about his writings) reveal many otherwise unknown details of Tolkien’s creation and his literary intentions. Taken together with Humphrey Carpenter’s

J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography

(1977), an authorized account for which Carpenter was given access to all of Tolkien’s papers, the

Letters

and the biography are the two best starting points for an understanding of Tolkien as a literary writer. To highlight just one additional book,

J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator

(1995), by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, shows another facet of Tolkien’s skills, collecting a large number of his own drawings and paintings, many of which depict scenes and landscapes of Middle-earth, thereby giving another, visual, means to appreciate Tolkien’s world.

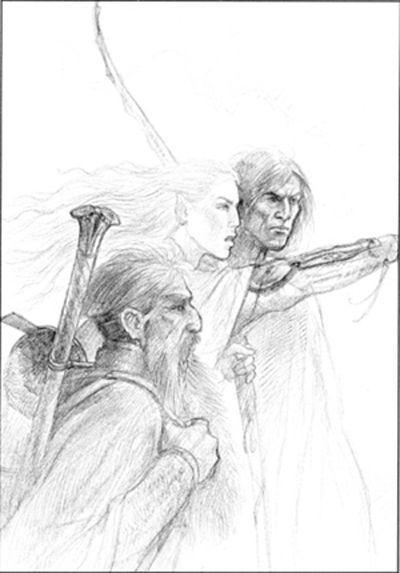

LEGOLAS, ARAGORN AND GIMLI

The Two Towers

Book 3, Chapter II: “The Riders of Rohan”

To turn finally to the critical response, from the very beginning Tolkien’s writings have evoked an initial reaction more emotional than intellectual. The reviews for

The Hobbit

at the time of its first publication are mostly pleasant, if occasionally a bit bewildered in trying to find a book to which to compare it. (In truth, none of the comparisons really work, for Tolkien was breaking new ground.)

Farmer Giles of Ham

, published twelve years after

The Hobbit

, didn’t garner much attention at all. But a few years later, with the publication of the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings, the polarization of response to Tolkien began in earnest. Though The Lord of the Rings is in fact a single novel, it was split up into three volumes for marketing reasons, as the publisher hoped that three volumes, priced competitively, would get three sets of reviews, while a much higher-priced single volume would be reviewed only once, and probably sell fewer copies. The publishing strategy worked.

Some very big names, including W. H. Auden, Naomi Mitchison, and C. S. Lewis (who was also Tolkien’s close friend), reviewed the books with high praise in high-profile periodicals, but others with equally big names did not like the books, and said so quite volubly. The single most notorious anti-Tolkien review is the one by Edmund Wilson entitled “Oo, Those Awful Ores!” that appeared in

The Nation

in April 1956. In it, Wilson claims to have read the whole novel out loud to his seven-year-old daughter (yet he curiously misspells the name of a major character as “Gandalph”) and calls The Lord of the Rings “essentially a children’s book—a children’s book that has somehow got out of hand, since, instead of directing it at the ‘juvenile’ market, the author has indulged himself in developing the fantasy for its own sake.” Herein lies the basic charge that most other detractors of Tolkien have leveled against him in the years following. The problem, for Wilson, is that the book is fantasy, and he thereby attempts to marginalize it by saying it is for children. A study of Wilson’s other critical writings shows that he had a marked dislike for almost any fantasy, although he did admit to liking the writings of James Branch Cabell, whose stories of Poictesme, a small imaginary kingdom of southern France, exhibit just the sort of risqué naughtiness and sexual innuendo that Wilson clearly expected to find in novels for “adults.”

The controversy about The Lord of the Rings raged again in the mid-1960s, after the books were published for the first time in paperback in the United States, and they reached the bestseller’s lists. But the basic argument against Tolkien remained mostly unchanged. The critic Harold Bloom has recently taken a slightly different tack in his dismissal of Tolkien, mistakenly confusing the widespread growth of Tolkien’s popularity in the 1960s with the idea that Tolkien’s works are thereafter to be considered as rooted in those times, culturally and historically. Bloom considers The Lord of the Rings to be what he calls (with capital letters) a “Period Piece”—presumably something that was once popular for some (to him) unfathomable reason, but was soon afterward forgotten. Bloom could not be more wrong.