Meditations on Middle-Earth (11 page)

Read Meditations on Middle-Earth Online

Authors: Karen Haber

Tags: #Fantasy Literature, #Irish, #Middle Earth (Imaginary Place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Welsh, #Fantasy Fiction, #History and Criticism, #General, #American, #Books & Reading, #Scottish, #European, #English, #Literary Criticism

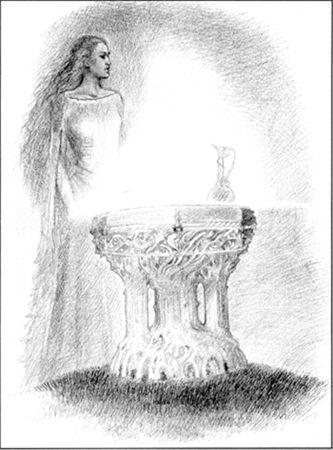

GALADRIEL

The Fellowship of the Ring

Chapter VII: “The Mirror of Galadriel”

I suppose the journey was a form of escapism. That was a terrible crime at my school. It’s a terrible crime in a prison; at least, it’s a terrible crime to a jailer. In the early sixties, the word had no positive meanings. But you can escape to as well

as from

. In my case, the escape was a truly Tolkien experience, as recorded in his

Tree and Leaf

. I started with a book, and that led me to a library, and that led me everywhere.

Do I still think, as I did then, that Tolkien was the greatest writer in the world? In the strict sense, no. You can think that at thirteen. If you still think it at fifty-three, something has gone wrong with your life. But sometimes things all come together at the right time in the right place—book, author, style, subject and reader. The moment was magic.

And I went on reading; and, since if you read enough books you overflow, I eventually became a writer.

One day I was doing a signing in a London bookshop and next in the queue was a lady in what, back in the eighties, was called a “power suit” despite its laughable lack of titanium armor and proton guns.

She handed over a book for signature. I asked her what her name was. She mumbled something. I asked again . . . after all, it was a noisy bookshop. There was another mumble, which I could not quite decipher. As I opened my mouth for the third attempt, she said, “It’s Galadriel, okay?”

I said: “Were you by any chance born in a cannabis plantation in Wales?” She smiled, grimly. “It was a camper van in Cornwall,” she said, “but you’ve got the right idea.”

It wasn’t Tolkien’s fault, but let us remember in fellowship and sympathy all the Bilboes out there.

A BAR AND

A QUEST

ROBIN HOBB

I

can’t write a scholarly essay about Tolkien. I’m not a scholar. Nor can I produce a carefully reasoned analysis of just how The Lord of the Rings changed not only fantasy but literature for my generation and generations to come. I am not only too close to it, I am at ground zero. I am a product of his impact. Like the rider in the rocket, I don’t know the mechanics of launching it or the thought that went into designing it. All I can tell you is that it carried me up to where I could see the stars, and nothing has looked quite the same since.

1965? I think that is right. Odd that I cannot put a more precise date to it. My family lived in a log house in a rural setting outside Fairbanks, Alaska. So I was about thirteen.

In the front yard of our log house, on stilt legs about fourteen feet tall, there was a small log cabin. In the dark cold of an Alaskan winter, in a good year, that cache was full of meat. Quarters of moose or caribou, frozen solid, leaned hooves-up against the walls. The hide was left on this grisly plenty to protect the meat from drying out. We had an electric freezer on the back porch as well, but the cache provided a space to store our hunting bounty until it could be cut into serving portions, wrapped in white paper and set into the plug-in freezer (which, often enough in the Fairbanks cold, was not plugged in for most of the winter!).

In summer, the cache served an entirely different purpose. It was mine. In a household rampant with seven siblings, not to mention their friends hanging out, it provided a small space of privacy for me. Bedrooms and living room had to be shared. No one except me wanted the cache. I could drag sleeping bags and cushions up there, and, for the summer at least, have my own room. With me went my books. Lots of books. Out of sight of both parents and siblings, I could hide from chores and the world at large, and read. One of the untrumpeted benefits of that Midnight Sun is that a flashlight is not necessary for late-night summer-reading. With plenty of Off! insect repellent and army-surplus mummy bag, my evening was complete.

This was the setting for not only my first reading of The Lord of the Rings, but for many repetitions of it. The sensory memories connected with those books are bumpy cottonwood logs under my back and glimpses of blue sky through the close-set logs of the cache’s roof.

I started with the Houghton Mifflin paperback with the pinky cover for

The Hobbit

, brought home from the rack at the drugstore. I went on to the Ace rip-offs for The Lord of the Rings. When I discovered that those who were courteous at least to living authors would not have bought the Ace editions, I saved rigorously and purchased all four books in Houghton Mifflin hardbacks. They cost me a whopping $5.95 each. It took me so long to acquire the whole set that the bindings did not match.

The Hobbit had

, of course, Tolkien’s own art on the cover. Two had jackets by Walter Lorraine, and the third had the darker art by Robert Quackenbush. But the covers didn’t much matter to me. It was the pages within that I needed to possess. The same hardback editions still sit on the shelves in my office. Their dust jackets are frayed and eroded. Opened, they lie flat, the stitching peeking out at me between the pages. Yet, opened to any page, the words still have the power to draw me in and pull me under, and, ultimately, to take me home.

I have lost track of how many times I have reread them over the years. Nor can I recall how many copies of The Lord of the Rings I have purchased over the years. They have been gifts for friends, both young and old; and there have been sets that went off to college with my children. The last time I reread

The Hobbit

was less than a month ago, as I shared it with my youngest daughter. I can recite the opening paragraph from memory, yet I never deliberately memorized it. Phrases and sensory images from the books float up into my mind at odd times: “fireweed seeding away into fluffy ashes,” winter apples that were “withered but sound,” or the smell of fresh mushrooms rising from a covered basket.

I suspect it is difficult for readers who have grown up in a time when

The Hobbit and

The Lord of the Rings are acknowledged as classics to understand the breathtaking impact they had on readers like myself. I simply had never read anything like it. I was an omnivorous reader, steeped in fairy tale books, the classics, mythology, mysteries, and adventure. In those days before I discovered Tolkien, I was devouring science fiction and pulp at the junkie rate of at least a paperback a day. It wasn’t that there was no good stuff out there. There was. I’d found Heinlein and Bradbury and Simak and Sturgeon and Leiber. All those encounters marked me. But Tolkien claimed me as no other writer ever had before.

His magic wrapped me and took me under, and when I came out of it, I was a different creature. Even as I sit here now, looking at a computer screen and trying to analyze why that is so, I am somewhat at a loss to explain it. Maybe it was the age I was, or the place I was in my development of reading taste. Maybe it was just the juxtaposition of Tolkien’s Middle-earth and the restless sixties. But perhaps magic doesn’t have to offer any explanation for why it worked. Perhaps it simply is.

Yet I think I can sieve out a bit of it. I had three distinct sensations at the end of The Lord of the Rings. One was the simple, unbelievable void of “It’s over. There’s no more of it to read.” The second was, “And I’ve never encountered anything like this. I’ll never find anything this good again.” The third was perhaps the most alarming: “In all my life, I will never write anything as good as this. He’s done it; he’s achieved it. Is there any point in my trying?”

Taking the third sensation first: Even in those days, I knew I was going to be a writer. I had been writing since I was in first grade, creating short stories almost as soon as I mastered sentences. By the time I finished junior high, I burned with the fixed ambition that I was going to write amazing books, someday. To discover that someone had already written the most amazing books that could possibly exist raised the bar to an almost impossible height for me.

Raising that bar was the most wonderful thing that anyone could have done for an ambitious young writer.

The fantasy I had read before that time simply didn’t take itself seriously. Before anyone sends me a list of a hundred serious fantasy books that existed before Tolkien wrote, let me concede that I completely accept all responsibility for my ignorance. I am sure there was important fantasy out there, and some of it had probably even made it to Fairbanks, Alaska. I’m simply saying that I hadn’t found it. Not until The Lord of the Rings.

Much of the fantasy I had read before Tolkien was unmistakably written “for children.” Some of it had that snide, winking-at-the-grown-up-in-the-room humor that some adults find amusing and children find irritating. (After all, if you think I’m that stupid, why are you writing for me?) Some was written with the kind of humor that becomes a barrier to the reader taking the character or story seriously. How can you care about the hero when his next contrived pratfall is probably less than a page away? Why commit to a character whom the writer has not invested in emotionally?

Much of what I read was sword-and-sorcery, rollicking adventurous stuff; fun, but written with a fine disregard for any morality regarding theft or mercenary murder. Serious, long-term relationships among the characters did not seem to exist. The happy ending was usually that the character managed to walk away unscathed and unchanged. Some of the fantasy I’d read was written in the simplistic “Once upon a time” format where the Prince and the Giant and the Glass Mountain are all capitalized, just to make sure the reader knows he is in the throes of a classic fairy tale. Even

The Hobbit

, much as I enjoyed it, was not devoid of some such condescension toward its characters.

Yet in

The Hobbit

I discovered elements that had never before shone so clearly for me. Setting was fully developed. True setting is far more than descriptive passages about birch trees in winter, or picturesque villages. Tolkien’s setting invoked a time and a place that was as familiar as home to me, yet unfolded the wonders and dangers of all that I had always suspected was just beyond the next hill. Here, too, were characters that rang as true as chimes, pompous Thorin and competent Balin, and Gandalf the wizard, subtle and quick to anger. I met them, and as the book progressed, I knew them. Tolkien allowed me to love them, without fear that on the next page I would discover the hollow cardboard or the contortion in the plot for the sake of a pun. Nor was the plot a linear thing, however the “There and Back Again” on the title page might imply it. It sprawled out in odd directions, touching older magics with the calm assumption that the reader would know they had always existed and always would. Magic rings and Mirk-wood were not issues that could be neatly cookie-cuttered to fit within the covers of this book. They extended beyond the edges of the page, and Tolkien made no apology for that. Like the maps in the hardbacks, his word unfolded larger than mere covers could encompass.

RIGENDELL

The Fellowship of the Ring