Masters of Death (47 page)

Dirlewanger’s methods were ruthless and effective, MacLean writes:

During these anti-partisan operations, Dirlewanger frequently rounded up women and children who had been left behind in the partisan villages and marched them through minefields which protected guerrilla positions. Needless to say, this technique killed and maimed many innocent people. In another tactic, Dirlewanger would fly in a light observation aircraft over suspected Russian villages. If he received gunfire from in or near a village he would annotate the location on a map. Later, he would return in a ground action, set fire to the entire hamlet and kill all the inhabitants. On these punitive operations there were no prisoners.

A participant, Hans-Peter Klausch, described one such village burning in a postwar deposition:

During a march—and we had driven 200 km close to Smolensk—the villages were encircled. Nobody was allowed to leave or enter. The fields were searched and the people were sent back to the village. The next morning around six a.m. all these people—it was a larger village with approximately 2,500 people—children, women, the elderly were pushed into four or five barns. Then Dirlewanger appeared with ten men, officers, etc., and said: “Shoot them all immediately.” In front of the barn, he positioned four SD men with machine pistols. The barn was opened and Dirlewanger said, “Fire freely.” Then there was indiscriminate shooting into the crowd of humans with the machine pistols, without distinction whether children, women, etc., were hit. It was a most horrendous action. The [machine pistol] magazines were taken out, new ones were inserted. Then new aiming started. After that, the barn was closed again. The SD men removed straw from the roofs and set the barns on fire. This was the most horrible spectacle which I have ever seen in my life. The barns were burning brightly. Nobody could escape until the barns fell down. Meanwhile, Dirlewanger and his staff positioned themselves with the Russian rapid-fire guns about fifty meters away from the barn. Then from the barns some lightly wounded, some heavily wounded and others who had not yet been hit stormed out, burning all over their bodies. Now these bastards shot these people who tried to escape, with Dirlewanger in front, until there was nobody left. I have witnessed this example which I have described in at least four or five other cases. Each of these villages was leveled down to the ground.

Sonderkommando Dirlewanger may appear to have been busy conducting draconian antipartisan missions, but much of its assigned work in fact supplemented continued Einsatzgruppe B and Order Police

Aktionen

against Byelorussian Jews. The relative numbers of victims in its reports confirm that SK Dirlewanger was not much more than yet another of Himmler’s Final Solution murder crews.

In April 1942 the remaining Jews of Vinnitsa were assembled at the local stadium for a selection. Hitler would not occupy Werwolf until mid-July, but it was time to tidy up. Tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, builders and others with letter A work permits were directed to the left and returned to the micro-concentration camps adjacent to the factories where they worked; the rest—the elderly, women and children, perhaps five thousand people—were directed to the right. These were marched or trucked by the Ukrainian auxiliaries under German supervision to the commercial nursery north of town where ten thousand had been murdered seven months before. A long grave gaped open at the nursery with planks on which to descend to the killing floor and a smiling German officer to offer the ladies a hand down. A Ukrainian killer with a machine gun sat on the rim dangling his feet into the pit, smoking a cigarette.

But ten feet from the long killing pit the Germans had opened a smaller, square pit perhaps twelve feet long and wide. As they drove the groups of victims to the long pit, they demanded the victims’ children— leading the little ones, pulling the babies from their mothers’ arms, shouting, shoving, beating, mothers screaming—and clubbed and shot the children separately into the separate pit while making a

Sardinenpackung

of the adults. Ukrainian historian Faina Vinokurova was unable to explain why the Germans killed the children separately at Vinnitsa, but two reasons suggest themselves: to keep the

Sardinenpackung

tidy, lining up the bodies of the adults; and, since children in their mothers’ arms were often shielded from the bullets that killed their mothers, to make sure the little Jews were killed before the pits were covered. In the same spirit, men from the Einsatzkommando had visited the maternity hospital in Vinnitsa that morning. New Jewish mothers and Jewish women in labor had been carried away to the Pyatnychany Forest and shot. The men had packed newborn Jewish babies into two gunnysacks, like unwanted kittens, and thrown the sacks out the second-floor window.

Himmler established field headquarters up the road in Zhitomir to be near the Führer. Göring built a bunker of his own three miles from

Werwolf,

went about Vinnitsa in an open car and supported the local ballet.

One of the most painful questions of the Holocaust, raised first of all by the SS perpetrators themselves, has been: Why did the Jews not resist? The question, with its ugly implication that the victims deserve blame— as if they murdered themselves—has many answers. Many victims did not know what was intended for them until after they had been brought under armed guard. Able-bodied men were usually seized first, leaving women, children and the elderly more vulnerable. The path to the killing pit or the transport was a gauntlet bristling with armed men and vicious dogs, with machine guns positioned on the perimeter. Running away meant leaving family members behind. The shock of encountering the killing pits was paralyzing. Resistance is more difficult stripped naked. It was unusual for Jews to own weapons or to have experience using them. Jewish communities faced with Gentile hostility traditionally negotiated. Mass killing on the Nazi scale was incomprehensible.

The majority of these answers coalesce around the obvious truth that Jewish communities in eastern Europe were more civilized—that is, socialized more to civil methods of settling disputes, populated with fewer individuals who were personally violent—than the Germans who assaulted them. They were also more civilized than most of the Gentile societies in which they were embedded. Jews historically had not conducted pogroms against Poles, Latvians, Lithuanians, Byelorussians, Ukrainians; it had been the other way around. “Preventive attack, armed resistance, and revenge,” Raul Hilberg writes, “were almost completely absent in Jewish exilic history.” Hilberg implies that the tradition of civility in Jewish ghetto culture was a weakness. It was a tragedy when confronted with Nazism; even, as Hilberg calls it, a catastrophe; but historically it had been a strength. Civil society in the West evolved across seven centuries from violent medieval beginnings to the modern rule of law; the Jews of eastern and western Europe, evolving civility more rapidly than their neighbors, hardly deserve blame for falling victim to a feral collectivity dominated by violent criminals. To the contrary, their neighbors deserve blame for having stood by and allowed the Holocaust to happen in their midst, especially since Bulgaria and Denmark gave convincing demonstration that even minimal resistance to Nazi demands could save lives.

Fewer eastern European Jews evidently brutalized their children than did Gentiles, producing fewer adults prepared to use serious violence even defensively. In that sense, the Jewish civil tradition was pacifist. One significant sign of less violent methods of child-rearing is the infant mortality rate in comparable populations. In Latvia in 1931, the Jewish infant mortality rate was about half that of Germans living in Latvia and of native Latvians and a third that of Lithuanians, Poles and Russians living in Latvia, and it maintained that difference across the decade even as health conditions improved and all but the Lithuanian infant mortality rate declined.

But the most obvious indication that a difference in civility left Jewish communities unprepared to resist concerted violent assault is the belated development of armed resistance in the ghettos the SS had organized in the East. “During the catastrophe of 1933–45,” Hilberg confirms, “the instances of opposition were small and few. Above all, they were, whenever and wherever they occurred, actions of last (never first) resort.” Violence is not only criminal. Civilized societies authorize violent officials to wield carefully limited violence to protect their citizens against criminal and military assault. The program of violent socialization that Lonnie Athens identified in the backgrounds of violent criminals is also visited upon and available to victims of illegitimate violence. When social controls over violence fail, as they failed for the Eastern Jews during the Second World War, reverting to private violence may be the only way to survive. German violent domination of Jewish ghettos gradually brutalized the ghetto population, and Jewish violent resistance emerged, especially among the young. They staged revolts, most memorably in Warsaw in April and May 1943, or escaped the ghetto into the forests and fought as partisans. Tragically, their sacrifices came too late to save many lives.

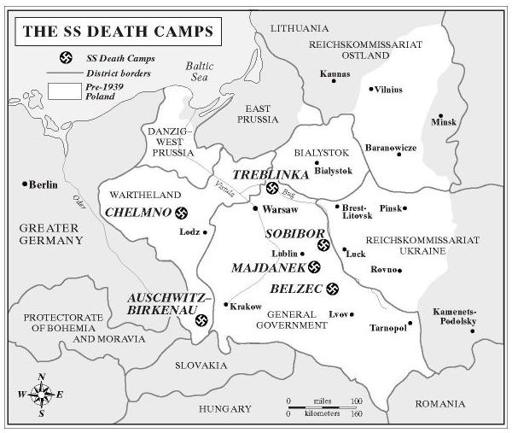

Routine extermination of Polish Jews began at Belzec on 17 March 1942; by the middle of June, when the transports were temporarily stopped to build new gas chambers, about ninety-three thousand people had been murdered there. In the late spring of 1942 the transports began moving again from the Third Reich to the East. Himmler met with Hitler on 16–17 April 1942, after which he traveled to occupied Poland and ordered the removal of Reich Jews from Lodz to Chelmno. Transports left Lodz beginning on 4 May 1942, and by the middle of May more than ten thousand people had been delivered to their death. The first Vienna transport to Minsk, to a killing site on a former collective farm east of Minsk at Maly Trostinets, left on 5 May 1942; seventeen more transports followed. Construction of the death camp at Sobibor, northeast of Lublin near the Bug River, began in March 1942, and routine operation followed beginning early in May; one hundred thousand victims were gassed there in the first two months.

At least one of the desk murderers was gone. On the morning of 27 May 1942 Heydrich had been returning to Prague from his nearby summer residence in his chauffeured Mercedes when four Czech patriots, two of them dropped in by parachute from England, ambushed him along a curve in the road and grenaded his car, driving fragments of leather, horsehair and steel springs from the back seat into his spleen. He chased his attackers and wounded one before he collapsed. Despite surgery and sulfonamide—an early antibiotic—he developed peritonitis and died of massive infection on 4 June 1942. His father had been a composer and music professor; Himmler told Lina Heydrich that in his delirium her husband had quoted a phrase from one of his father’s operas: “Yes, the world is but a barrel organ, which our Lord God turns himself, and each must dance to the tune.” SS-Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich’s benediction on the Blond Beast who organized the Final Solution might be the world’s: “Is the swine dead at last?”

After a state funeral in Berlin on 8 June 1942 with Hitler and Himmler prominently at hand, Himmler spoke to his Gruppenführers and department heads. “War is no matter of sentimentalities,” he told them, continuing a little later:

Even if it is so desperate—one can do no more than die. I have the conviction now—which we all have—that in the final analysis the others will die sooner than us. In the final analysis we have the thicker skull. We have the better blood, the stronger heart and the better nerves. Good, our comrade Heydrich, our friend Heydrich, is now dead, he lies under the sod. Now the whole SS—and I can assure you that if he lived he would say exactly the same—will march on with beating drums and helmets donned. And if another blow strikes us, we will march on. And if we have attacked ten times, will attack an eleventh time. So long as one man in any position, in a company, in a platoon remains who can crook a finger round a trigger, all is not lost.

He went on, a matter of sentimentalities, to evoke the future he was planning of settlements in the East, fussing over budgets but also alluding to the Final Solution:

If we do not make the bricks here, if we do not fill up our camps with slaves—in this context I say things very plainly and very clearly— with work-slaves to build our towns, our villages, our farmsteads without regard to any losses, then after a long war we will simply not have the money to furnish the settlements so that really Germanic people can live there and take root in the first generation.

I said the first great peace task is to overhaul the whole SS and police and to fuse them together. The second task is to fetch in and fuse the Germanic peoples with us. The third task is the settlement and migration of peoples in Europe which we are carrying out. The migration of the Jews will be dealt with for certain in a year: then none will wander again. Because now the slate must be made quite clean.

In mid-July 1942 Himmler ordered the “resettlement” of the entire Jewish population of the General Government—that is, their murder— by the end of the year. Treblinka, a death camp built northeast of Warsaw beginning in late May or early June 1942 with engine-generated carbon monoxide gas chambers, began receiving transports from the former Polish capital on 22 July; by the end of August two hundred thousand people had been gassed there, with tens of thousands more to follow.