Making a Point (2 page)

Authors: David Crystal

2

⦠was diversity

Diverse punctuation practice is inevitable when there are several ways of marking the same thing. Inserting spaces is one way of separating words, but there are others. Here's a selection:

thisisnotanexampleofwordseparation

this is an example of word separation

this.is.an.example.of.word.separation

this+is+an+example+of+word+separation

thiSiSaNexamplEoFworDseparatioN

ThisIsAnExampleOfWordSeparation

this-is-an-example-of-word-separation

The last two are ways around the domain-name problem mentioned at the end of the previous chapter. If we can't use spaces to make it easier to read the words in an Internet address, then we can use hyphens or the curiously but aptly named âcamel case' (as in the two examples showing a mix of upper-case and lower-case letters).

In Anglo-Saxon times, we see a similar diversity, reflecting an earlier variability that was present among the writers of ancient Rome. People experimented with word division.

Some inscriptions have the words separated by a circle (as with the Undley bracteate) or a raised dot. Some use small crosses. Gradually we see spaces coming in, but often in a very irregular way, with some words spaced and others not â what is sometimes called an âaerated' script. Even in the eleventh century, less than half the inscriptions in England had all the words separated.

The slow arrival of word division in inscriptions isn't so surprising when we consider their character. The texts that identify jewels, boxes, statues, buildings, swords, and so on are typically short and often predictable. If people know their church is called âSt Ambrose', then they will read its name (if they are able to read) regardless of how it is spaced. Nobody would interpret STAMBROSE as STAM + BROSE. Also, the physical environment makes punctuation unnecessary. If the aim of a full stop is to tell readers that a sentence has come to an end, then the boundary of a physical object will do that just as well. It's no different today. We don't need a full stop at the end of a sign saying WAY OUT. The right-hand edge of the sign is enough to show us that the message is finished.

If they are able to read ⦠In Anglo-Saxon times, most people couldn't. Only a tiny elite of monks, scribes, and other professionals knew how to write; so there was no popular expectation that inscriptions should be easy to read. Nor was there any peer-group pressure among inscribers. In a monastery, there would be a scribal tradition to be followed and a strict hierarchy, with junior scribes copying the manuscript practices of their seniors. By contrast, the sculptor or goldsmith producing an inscription would be someone working alone, with no guidance other than his own sense of tradition and aesthetic taste. Divergent punctuation practices were an inevitable result.

We see a similar diversity when we read the earliest

surviving Anglo-Saxon manuscripts â the meagre collection of glossaries, charters, wills, name-lists, poems, riddles, and religious texts from the seventh and eighth centuries that give us our first real sense of what Old English was like. Manuscripts, of course, are very different from inscriptions, as they contain sentences of varying complexity extending over several pages. They can also be revised and corrected, either by the original scribe or by later readers. But these early texts have one thing in common: unlike the inscriptions, they all display word-spaces.

By the seventh century in England, word-spacing had become standard practice, reflecting a radical change that had taken place in reading habits. Silent reading was now the norm. Written texts were being seen not as aids to reading aloud, but as self-contained entities, to be used as a separate source of information and reflection from whatever could be gained from listening and speaking. It is the beginning of a view of language, widely recognized today, in which writing and speech are seen as distinct mediums of expression, with different communicative aims and using different processes of composition. And this view is apparent in the efforts scribes made to make the task of reading easier, with the role of spacing and other methods of punctuation becoming increasingly appreciated.

In some cases, the nature of the genre made word-spacing inevitable. The earliest English manuscripts are alphabetical glossaries containing lists of Latin words with their English equivalents â essential aids for the many monks who were having to learn Latin as a foreign language. But imagine a glossary with no word-spaces! The different entries would run into each other and the whole thing would become unusable. Bilingual glossaries â as modern bilingual dictionaries â need good layout for readers to find their way about.

Word-spaces are inevitable, also, when glossing a continuous text. There's a copy of the Book of Psalms dating from around 825, known as the Vespasian Psalter. It's in Latin, with the words spaced, but someone has added word-by-word English translations â over 30,000 of them â above the Latin words in the space between the lines. Each gloss is easily visible, at a distance from its neighbours. Once again, the layout dictates the spacing.

What happens in genres where the text is a series of sentences, rather than a series of isolated words? Here too we see word-spacing, but the situation is more complex. Very often, some spaces are larger than others, probably reflecting a scribe's sense of the way words relate in meaning to each other. A major sense-break might have a larger space. Words that belong closely together might have a small one. It's difficult to show this in modern print, where word-spaces tend to be the same width, but scribes often seemed to think like this:

we bought a cup of tea in the cafe

The âlittle' words, such as prepositions, pronouns, and the definite article, are felt to âbelong' to the following content words. Indeed, so close is this sense of binding that many scribes echo earlier practice and show them with no separation at all. Here's a transcription of two lines from one of Ãlfric's sermons, dated around 990.

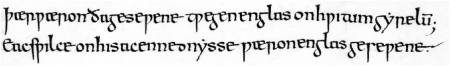

þærwæronðagesewene twegenenglas onhwitumg

relū;

þær wæron ða gesewene twegen englas on hwitum g

relū;

âthere were then seen two angels in white garments'

Eacswilc onhisacennedn

sse wæronenglasgesewene'.

Eacswilc on his acennedn

sse wæron englas gesewene'.

âsimilarly at his birth were angels seen'

Lines from the manuscript of Ãlfric's sermon âIn ascensione domini', British Library, Royal MS 7 C.xii, f.105r. The handwriting is Anglo-Saxon minuscule in its square phase

, c

.990

.

The word-strings, separated by spaces, reflect the grammatical structure and units of sense within the sentence. And a careful examination of the original text shows an even more subtle feature. Normally the letter

e

is written much as we do today, as in the first two

e

's in

acennedn sse

sse

; but when the

e

appears before the space, its middle stroke is elongated, acting as a bridge between the two word-strings. It's an early kind of letter-joining, or

ligature

.

The Ãlfric sermon is quite late, for an Anglo-Saxon text, but its use of word-strings and variable word-spaces is typical of the time, and the practice continues until the very end of the Old English period. The extract also shows the presence of other forms of punctuation (which I'll discuss in the next chapter). Taken together, even in just two lines of text it's possible to sense that there has been a major change in orthographic behaviour compared with the unspaced, punctuationless writing seen in the English inscriptions and in traditional Latin.

The origins of the change are not simply to do with the development of new habits of reading. They are bound up with the emergence of Christianity in the West, and the influential views of writers such as St Augustine. Book 3 of his (Latin) work

On Christian Doctrine

, published at the end of the fourth century AD, is entitled: âOn interpretation required by the ambiguity of signs', and in its second chapter we are

given a ârule for removing ambiguity by attending to punctuation'. Augustine gives a series of Latin examples where the placing of a punctuation mark in an unpunctuated text makes all the difference between two meanings. The examples are of the kind used today when people want to draw attention to the importance of punctuation, as in the now infamous example of the panda who

eats, shoots and leaves

vs

eats shoots and leaves

. But for Augustine, this is no joke, as the location of a mark can distinguish important points of theological interpretation, and in the worst case can make all the difference between orthodoxy and heresy.