Made In America (17 page)

Authors: Bill Bryson

The Gettysburg address also marked a small but telling lexical transition. Before the Civil War people generally spoke of

the Union,

with its implied emphasis on the voluntariness of the American confederation. In his first inaugural address Lincoln used

Union

twenty times, and

nation

not at all. By the time of the Gettysburg address, the position was reversed. The address contains five mentions of

nation

and not one of

union.

We have come to take for granted the directness and accessibility of Lincoln's prose, but we should remember that this was an age of ludicrously inflated diction, not only among politicians, orators and literary aesthetes, but even in newspapers. As Cmiel notes, no nineteenth-century journalist with any self-respect would write that a house had burned down, but must instead say that âa great conflagration consumed the edifice'. Nor would he be content with a sentiment as unexpressive as âa crowd came to see' but instead would write âa vast concourse was assembled to witness'.

33

In an era when no speaker would use two words when eight would do, or dream of using the same word twice in the same week, Lincoln revelled in simplicity and repetition. William Seward, his Secretary of State, drafted Lincoln's first inaugural address. It was a masterpiece of the times. Lincoln pruned it and made it timeless. Where Seward wrote: âWe are not, we must not be, aliens or enemies, but fellow-countrymen and brethren,' Lincoln changed it to âWe are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.â

34

Such succinctness and repetition were not just novel, but daring.

His speeches were constantly marked by a distinctive rhythm â what Garry Wills calls âpreliminary eddyings that yield to lapidary monosyllables', as in âThe world will little

note, nor long remember, what we say here' and âWe shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.â

35

Always there was a directness about his words that stood in marked contrast to the lofty circumlocutions of the East and marked him as a product of the frontier. âWith malice towards none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right ... let us strive ... to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations' from Lincoln's second inaugural address may not seem on the face of it to have a great deal in common with Davy Crockett's âlike a chain lightning agin a pine log', but in fact it has precisely the same directness and simplicity of purpose, if phrased with somewhat more thoughtful elegance.

American English had at last found a voice to go with its flag and anthem and national symbol in the shape of Uncle Sam. At the same time it had found something else even more gratifying and more certain to guarantee its prospects in the world. It had found wealth â wealth beyond the dreams of other nations. And for that story we must embark on another chapter.

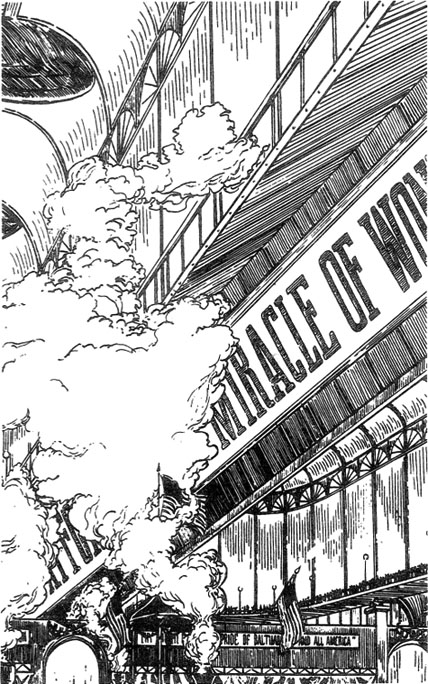

Dame Railway and Her Choo-Choo Court, Cincinnati Ironmongery Fair, 1852

We're in the Money: The Age of Invention

On the morning of 2 July 1881 President James Garfield, accompanied by his Secretary of State, James G. Blaine, was passing through the central railway station in Washington, DC, to spend the Fourth of July holiday on the New Jersey shore with his family. His wife had only recently recovered from a nearly fatal bout of malaria and he was naturally anxious to be with her. In those days there was no Secret Service protection for the President. On occasions such as this the President was quite literally a public figure. Anyone could approach him, and one man did â a quietly deranged lawyer named Charles Guiteau, who walked up to the President and calmly shot him twice with a .44-calibre revolver, then stepped aside and awaited arrest. Despite a notable absence of qualifications Guiteau had long pestered the President to make him chief consul in Paris.

The nation waited breathlessly for news of the President's recovery. Newspapers all over the country posted frequent, not to say strikingly candid, bulletins outside their main offices. âThe President was somewhat restless and vomited several times during the early part of the night. Nutritious enemata were successfully employed to sustain him,' read a typical one on the façade of the

New York Herald

office.

1

As the President slipped in and out of consciousness, the

greatest minds in the country were brought to his bedside in the hope that someone could offer something more positively beneficial than rectal sustenance. Alexander Graham Bell, at the peak of his fame, devised a makeshift metal-detector, which he called an âinduction balance' and which employed his recently invented telephone as a listening aid. The intention was to locate the bullets lodged in the President's frame, but to Bell's considerable consternation, it appeared to show bullets practically everywhere in the President's body. Not until much later was it realized that the device had been reading the bed springs.

The summer of 1881 was one of the sultriest for years in the nation's capital. To provide some relief for the stricken President, a corps of naval engineers who specialized in ventilating mine shafts was summoned to the White House and instructed to build a cooling device. They rigged up a large iron box filled with ice, salt and water, and a series of terry-cloth filters which were saturated by the melting ice. A fan drew in warm air from outside, which was cooled as it passed over the damp terry-cloth and cleansed by charcoal filters, and was propelled onwards into the President's bedroom. The device was not terribly efficient â in fifty-eight days it consumed a quarter of a million tons of ice â but it worked up to a point. It cooled the President's room to a more or less tolerable 81 °F, and stands in history as the world's first air-conditioner.

2

Nothing, alas, could revive the sinking President, and on the evening of 19 September, two and a half months after he had been shot, he quietly passed away.

The shooting of President Garfield was significant in two ways. First, it proved once and for all the folly of the spoils system, a term inspired by the famous utterance of New York politician William E. Marcy sixty years earlier: âTo the victor belong the spoils.â

3

Under the spoils system it fell to a newly elected President to appoint hundreds of officials, from rural

postmasters and lighthouse keepers to ambassadors. It was a handy way to reward political loyalty, but it was a tediously time-consuming process for a new President and â as Charles Guiteau conclusively demonstrated â it bred dissatisfaction among disappointed aspirants. Two years later Congress abolished the practice. But the shooting of the President â or more precisely the response to the shooting â was significant in another way. It underlined the distinctively American belief that almost any problem, whether it be finding a bullet buried in soft tissue or cooling the bedroom of a dying Chief Executive, could be solved with the judicious application of a little know-how.

Know-how,

dating from 1857, is a quintessentially American term and something of a leitmotif for the nineteenth century. Thanks to it, and some other not insignificant factors like an abundance of natural resources and a steady supply of cheap immigrant labour, America was by 1881 well on its way to completing a remarkable transformation from an agrarian society on the periphery of world events to an economic colossus. In the thirty years that lay either side of Garfield's death America enjoyed a period of growth unlike that seen anywhere in history. In almost every area of economic activity, America rose like a giant, producing quantities of raw materials and finished products that dwarfed the output of other countries â sometimes dwarfed the output of all other countries put together. Between 1850 and 1900, American coal production rose from 14 million tons to over 100 million, steel output went from barely 1 million tons to over 25 million, paper production increased ninefold, pig-iron production sevenfold, cotton-seed oil by a factor of fourteen, copper wire by a factor of almost twenty. In 1850 America's 23 million people had a cumulative wealth of $7.1 billion. Fifty years later, the population had tripled to 76 million, but the wealth had increased thirteen-fold to $94.3 billion.

4

In 1894 America displaced Britain as

the world's leading manufacturer. By 1914 it was the world's leading producer of coal, natural gas, oil, copper, iron ore and silver, and its factories were producing more goods than those of Britain, Germany and France together. Within thirty years of Garfield's death, one-fourth of all the world's wealth was in American hands.

For the average American, progress was not, in the words of Henry Steele Commager, âa philosophical idea but a commonplace of experience ... Nothing in all history had ever succeeded like America, and every American knew it.â

5

In no other country could the common person enjoy such an intoxicating possibility of accumulating wealth. An obsession with money â and more specifically with the making of money â had long been evident in the national speech. As early as the eighteenth century, Benjamin Franklin was reminding his readers that âtime is money' and foreign visitors were remarking on the distinctly American expression âto net a cool thousand',

6

and on the custom of defining a person as being âworth so-and-so many dollars'. Long before Henry Clay thought up the term in 1832, America was the land of the âself-made man'.

7

At about the same time people began referring to the shapers of the American economy as âbusinessmen'. The word had existed in English since at least 1670, but previously it had suggested only someone engaged in public affairs.

8

In the sense of a person concerned with the serious matter of creating wealth it is an Americanism dating from 1830. As the century progressed people could be

well-fixed

(1822),

well-to-do

(1825),

in the dimes

(1843),

in clover

(1847),

heeled

(1867;

well-heeled

didn't come until the twentieth century), a

high roller

(1881), or a

money-bag

(1896, and made into the plural

money-bags

early in this century). As early as the 1850s they could hope to

strike it rich

and by the 1880s they could dream of

living the life of Riley

(from a popular song of the period, âIs That Mr Reilly?', in which the hero speculates on what he would do with a fortune).

9

Not everyone liked this new thrusting America. In 1844 Philip Hone, a mayor of New York and a noted social critic, wrote âOh, for the good old days', the first use of the phrase.

10

But most people, then as now, wanted nothing more than to get their hands on âthe almighty dollar', an expression coined by Washington Irving in 1836 in an article in the

Knickerbocker Magazine

.

11

A great many of them did. As early as the mid-1820s, Americans were talking admiringly of

millionaires,

a term borrowed from the British who had in turn taken it from the French, and by 1850 were supplementing the word with a more aggressive version of their own devising:

multimillionaires.

12

An American lucky enough to

get in on the ground floor

(1872) with an arresting invention or a timely investment might reasonably hope to become a millionaire himself. In 1840 the country had no more than twenty millionaires. By 1915 there were 40,000.

13

The new class of

tycoons

(from the Japanese

taikun,

'military commander', and first applied to business leaders in the 1870s) enjoyed a concentration of money and power that is almost unimaginable now. In 1891 John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil controlled 70 per cent of the world market for oil. J. P. Morgan's House of Morgan and its associate companies in 1912 were worth more âthan the assessed value of all the property in the 22 states and territories west of the Mississippi'.

14

With great wealth came the luxury of eccentricity. James Hill of the Great Northern Railroad reportedly fired an employee because the man's name was Spittles. The servants at J. P. Morgan's London residence nightly prepared dinner, turned down the bed and laid out nightclothes for their master even when he was known beyond doubt to be three thousand miles away in New York. The industrialist John M. Longyear, disturbed by the opening of a railroad line past his Michigan residence, had the entire estate packed up â sixty-room house, hedges, trees, shrubs, fountains, the

works â and re-erected in Brookline, Massachusetts.

15

James Gordon Bennett, a newspaper baron, liked to announce his arrival in a restaurant by yanking the tablecloths from all the tables he passed. He would then hand the manager a wad of cash with which to compensate his victims for their lost meals and spattered attire. Though long forgotten in his native land, Bennett and his exploits â invariably involving prodigious drinking before and lavish restitution after â were once world famous, and indeed his name lives on in England in the cry âGordon Bennett!', usually uttered by someone who has just been drenched by a clumsy waiter or otherwise exposed to some exasperating indignity.