Mac Hacks (4 page)

. Get to Know Your User Account

Permissions are crucial to the functioning of OS X, and a basic

understanding of them will make your hacking forays not only more fruitful

but also less fearful.

You likely know that OS X is based on Unix, an operating system

invented in Bell Labs that has been around since 1969. In 1969 the idea of

a personal computer was pretty far fetched—computers were hugely expensive

and computer time was very valuable. Because of that, Unix was designed to

be a multiuser system. As such, it needed a method for deciding just what

each user can do with the machine. (It would be bad if one student could

erase another student’s work or, the other extreme, a setup where only one

superuser could make any changes at all.) Permissions allow users to

change what they need to change while protecting others who use the same

machine from accidental data deletion.

When

you first set up OS X, you provided a name, OS X suggested

a short name which you may or may not have chosen to use, and you were off

to the races. “No big deal,” you might think, “this is just routine

housekeeping when setting up a new machine.” Actually, this step

is

kind of a big deal—the first account you set up in

OS X is, by default, an administrator account.

OS

offers three main types of accounts: Administrator,

Standard, and Managed with Parental Controls. (There are other types

listed in the Users & Groups preference pane, but the ones listed

above are your best bets for everyday use.) Administrators have a lot of

power in OS X—they can make global changes that impact

everyone

who uses that computer—so logging in as an

administrator for day-to-day use isn’t the best idea; with that much power

over the entire system, you can cause serious harm to your account and

others’. It’s much better to log in as a standard user for day-to-day

tasks while reserving the administrator account for those times you need

to, well, administrate. Standard

users can make changes that impact their own accounts, and

Managed users can only do what the administrator

specifically allows. The Standard account is the sweet spot because you

get to control the stuff you need to control, but you can’t mess up anyone

else’s work or the machine.

The most obvious objection to switching to a standard user account

is that you’re already using one account and you don’t want to re-create

everything for your new account. That’s a valid objection—but one we can

work around.

A

standard user on OS X has plenty of control over their

information and preferences. Preferences for each user are stored in

each user’s Home folder’s Library. The Library is what makes your Mac

feel like it’s yours. You might want to directly tweak the files in your

Library, but if you go poking around in your Home folder, you won’t see

anything that looks like it might be storing your preferences and the

like. That’s because those things are stored in the Library folder and,

starting in OS X Lion, Apple made that folder invisible.

This can be frustrating for longtime Mac users who are used to

messing around in that folder. For example, an app is giving you a ton

of problems, you might want to jump to the Library folder and delete

your preferences for that program, which can sometimes make the app more

responsive (the preferences will be regenerated).

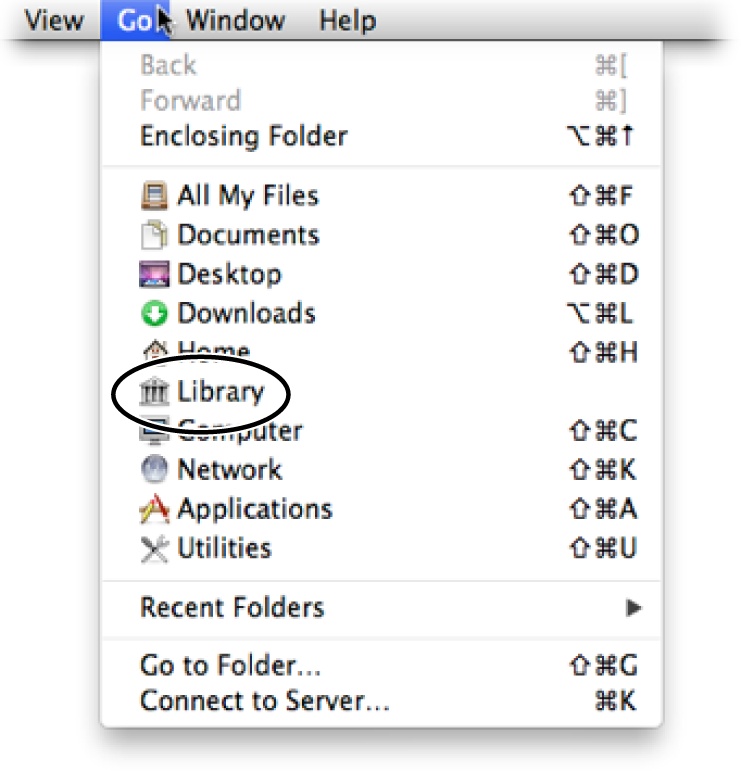

Fortunately, Apple gives you a simple way to access your Library

folder. In the Finder’s menu bar, open the Go menu and then press the

Option key. Voilà—a Library option appears in the menu (

Figure 1-8

)!

way to find your Library folder, but it’s probably the easiest.

Account

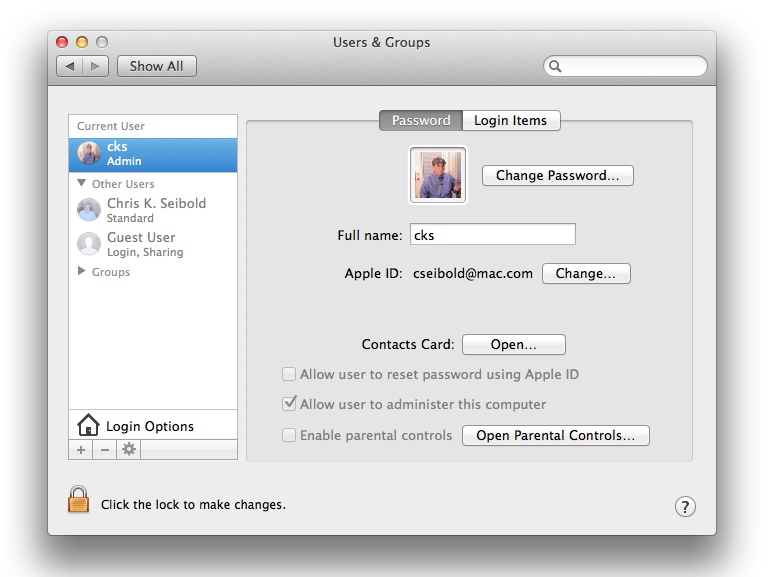

Fire

up System Preferences and head to Users & Groups.

You’ll see a list of users on the left side of the pane with the current

user at the very top. Immediately under each user’s name is a label that

indicates what kind of user they are (

Figure 1-9

).

the Login Items tab if you want programs to start automatically when

you log in.

If you only have one administrator account, you can’t really

change your account status because your Mac has to have at least one

admin-level user. In that case, the first step is to add another

administrator user. Click the lock icon in the pane’s lower-left corner

and then type in your administrator password in the window that appears.

Once the pane is unlocked, you can add a new account. Click the + button

above the lock icon and a new window will appear (

Figure 1-10

).

Fill

out the fields and pick a good password (click the key

icon if you want Password Assistant to help you pick a secure one);

write yourself a meaningful hint and click Create User. You now have

two

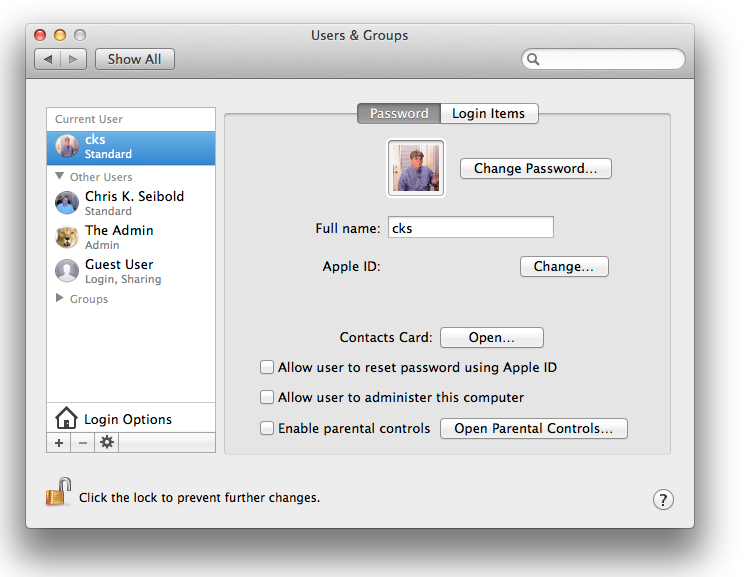

administrator accounts. Now you’re ready to

make your original admin account into a standard account: click your

original account in the list on the right side of the preference pane,

and then uncheck the box that says “Allow user to administer this

computer” (

Figure 1-11

).

That’s it—you’ve turned your overly powerful administrator account into

a safe-to-use-daily standard account! (Well, after you restart your

machine, anyway.) In

Figure 1-11

, a former

administrator account has become a standard account.

You might be experiencing some regret at this point. What about

all the power you gave up? How will you get things done when you need to

be an administrator to accomplish something? Will you have to log out

and log back in? Don’t fret: everything will be almost exactly the same.

You’ll still have all the same powers, you’ll just have to occasionally

enter the admin username and password you just created instead of the

password associated with your now-standard account—a small price to pay

for increased

security.

day-to-day use; instead, you’ll use it on those special occasions when

you want to boss your computer around for a bit.

sleep soundly at night.

Now

you know the safe way to do things when it comes to user

accounts, but that method might not be to your liking. You might be one

of those folks who wants to control

everything

—you’re so certain of your abilities that

you don’t want to stumble along using a standard account to safeguard

other users’ data or the integrity of your machine. If you’re one of

those people, the root account may be for you.

Warning: Enabling a root account is a bad idea—a

really

bad idea.

Don’t do

it

. You can accomplish anything you want to by just being

an administrator user or authenticating when you’re trying to do

something potentially damaging. But if you

still

insist on being lord of the realm, this section explains what to

do.

You’ve been warned, but if you want to go ahead and enable the

root account anyway, the process is simple. Open the Users & Groups

preference pane, click the lock icon and enter your admin credentials,

and then click Login Options. In the pane’s list of settings, click the

Join button. Doing so will display a pane where you can enter a server

for your Mac to look at. You don’t need to worry about which server to

choose. Just click the Open Directory Utility button and marvel at the

Directory Utility window (

Figure 1-12

).

for bad acronyms? Nope. Even though this window might not make any

sense at all in light of what you’re trying to do, this is exactly

where you want to be.

You are about to become the supreme overlord of your Mac. First,

unlock the pane by clicking the lock icon and authenticating. Next, head

to the top of your screen, click Edit, and then select Enable Root User,

You’ll see some fields you can use to create a password for the newly

enabled root user. Enter the password and bang—you’ve got a root user

for your Mac!

To log in as the root user, log out or switch users. You’ll see an

option on the Login screen named Others. Choose this option and then

type inrootfor the login name

and the password you created for that account.

Once you’re logged in as the root user, you can do anything you

want. You can look at any file on your machine (even other people’s)

delete any directory, delete any file, or completely ruin the system on

a whim. Logging in as root isn’t

necessarily

dangerous if you’re very careful with what you do while you’re logged

in, but a moment’s lapse of attention and you can do serious

damage.

Note: If

you don’t administer the Mac you use, you might be

worried that the administrator could log in as root and see all your

personal files. That’s certainly possible. The way to prevent that is

to move your home directory to a portable media you can physically

control (see

[Hack #35]

) or

encrypt the data using FileVault 2 (

[Hack #34]

).