LoveStar (4 page)

Authors: Andri Snaer Magnason

Tags: #novel, #Fiction, #sci-fi, #dystopian, #Andri Snær Magnason, #Seven Stories Press

HONEY

When Indridi and Sigrid's life was sweet as honey, they woke in the morning sunshine as if glued together with it. Not intoxicating Chicago honey but pure, golden, sugary royal honey. Palm clasped to palm, bodies pressed together, and legs so entwined that it was hard to see which foot belonged to which body.

“Honey,” murmured Indridi and removed his tongue from Sigrid's mouth to say good morning, but she pouted and sucked his tongue back between her lips, hugging him closer and clamping her thighs around him. They lay like this for a good half hour, and although he was inside her, they weren't exactly having sex. It was more an extension of their embrace, a question of maximum unity and surface contact. The feeling that they were not only one soul but also one and the same body.

Although they found it almost impossible to tear themselves apart, they crawled together into the living room, more like an eight-footed spider than a cartwheel on its spokes, and when their mouths parted at last she let fall a word. Just one tiny word and then the dam burst because the word precipitated a chain reaction in their brains. The words flowed in and out of them like a cycle. Biologists would have said that they were nourished by the word-synthesis that streamed through them, round and round. They lay on the floor for a good while, talking and giggling and fooling around because together they were as complete and true as a circle.

They were not nourished by words alone but also by silence. When they fell silent the silence was so rich and the feeling so resonant with meaning and understanding that when one of them broke it with a word or sentence it was frequently to add to what the other had just been thinking.

Of course, Indridi and Sigrid had to work like other people and after they made love on the kitchen floor while they were waiting for the kettle to boil, Indridi managed to use the last of his strength to free himself from the honey-glue and Sigrid slipped into a jumper and panties. With a combined effort they were able to get dressed and part their lips long enough to eat breakfast, though without completely ceasing to touch. Then they gazed long and deep into one another's eyes to say a reluctant: “Bye, see you at lunchtime.”

But love had not had its final word. They left the house together and Indridi stood on the street corner, staring after Sigrid as she walked backward along the pavement toward the geriatric unit down the road. Indridi used hand signals to let her know if she was steering into flowerbeds or bushes. When she reached the junction she stopped and blew Indridi a kiss before taking the big step: out of sight. It was as if a cloud had covered the sun. Their hearts beat lonely and forlorn in their dark rib-casings and they missed each other so inexpressibly much that they just had to ring:

“Where are you?” asked Indridi.

“I'm here around the corner.”

“Do you miss me?”

“Yes, I miss you.”

“Shall we take a peep?”

“Yes, let's peep one more time.”

They retraced their steps, peeped around the corner, and waved to one another. Sometimes they couldn't stop themselves from running back together and letting a few beautiful words flow from lips into ears where they turned into a thrilling, tingling electric current that undulated like the Northern Lights over the dark surface of their brains. Indridi held her around the waist and they gazed into each other's eyes.

“I missed you,” he said.

“It's so hard to part,” said Sigrid, looking apprehensively at the geriatric unit down the road.

“See you at lunchtime,” said Indridi.

“Bye,” said Sigrid. After the good-byes they stood speechless for ten more minutes, neither able to take the first step, until at last they said “one, two, go” and ran straight to work without looking over their shoulders; they were both late.

At lunchtime Indridi and Sigrid would sometimes cycle down to the harbor and sit in a café on the docks. Above them towered the Statue of Liberty, a one-thousand-foot-tall statue of Leif Eriksson straddling the harbor entrance with moles under his stone feet. It was LoveStar who donated the giant Viking hero to the nation, the largest statue of liberty in the world, which bore a suspicious resemblance to LoveStar himself. The statue stared out at the restless sea, eternal flames of liberty burning in his eyes to guide the snow-white cruise ships as they sailed to land like capelin-laden trawlers. When the gangway was extended, a thousand impatient, love-craving customers poured from the ship and hastened as fast as they could go north to the ever-green Oxnadalur valley where sheep bleated, foxes yapped, love was proven, and LOVESTAR twinkled behind its cloud.

On fine days trucks would stream back down south with piles of lovers cuddled up in soft hay, then dockworkers would strap the couples into harnesses and they'd dangle over the harbor like eight-footed horses before being lowered into the ship's hold. Indridi and Sigrid had half an hour to word-synthesize. In their eyes glowed happiness itself, bright as LOVESTAR.

Indridi and Sigrid's love had grown in the five or so years that they had been together, and their love was not just a little seed in their hearts but had put down roots and tentacles all over their bodies, right into the extremities of their limbs, making their fingertips as sensitive as clitorises. When Indridi and Sigrid held hands they stroked their middle fingers together, causing a strangely thrilling sensation to spread through their bodies and calling forth a mysterious smile upon their lips.

Many people regarded Indridi and Sigrid's love as an obstacle; Sigrid's mother went so far as to call it a handicap. Indridi and Sigrid had, for example, both given up being cordless modern employees. They had made many attempts to enjoy the free, flexible working hoursâat home, at the summer house, or on a romantic beachâbut it never worked out in the long run. If no one insisted that they be at a given place at a given time, they got nothing done and were tempted to steal a kiss or caress, which ended often enough with them lying cuddled up and satiated in bed.

So Sigrid gave up her career as a cordless construction engineer and got a job at a geriatric unit where she tended to old people before they were sent north to LoveDeath. Her mother, who had grander ambitions for her daughter, regarded the job as beneath her dignity and talents.

“Did Indridi push you into this meat processing?”

“Don't call it meat processing, Mom.”

“But you're not a free person!”

“Freedom doesn't suit us, Mom,” said Sigrid, smirking at the thought. “We don't get anything done.”

“Does Indridi have to be glued to you the whole time?”

“It's me too, Mom,” said Sigrid. “He's not the only one who wants to stick together.”

Indridi had sacrificed his career as a cordless web designer and got a job tending and cultivating the grounds around the Puffin Factory. They took quite a drop in wages, but Indridi and Sigrid had no regrets. According to

REGRET

it was just as well they had got together, otherwise Indridi would have been killed outright in a car accident while Sigrid would have ended up an addict and drowned during a swimming-pool party.

While Indridi and Sigrid sailed through their days on a pink cloud, Sigrid's mother saw nothing but a black shadow looming over them.

“Sigrid dear, I've booked you an appointment with a specialist.”

“Oh?”

“You're so young and innocent. It'll be such a shock for you when you break up.”

“You needn't worry about me,” said Sigrid archly. “We're never going to break up.”

“Statistics, Sigrid dear,” said her mother, shaking her head. “You can't beat statistics.”

Indridi and Sigrid weren't about to let any statistics overshadow their love. Those who were interested could let their eyes wander and follow their lives in their cozy apartment at: Hraunbær90(3fm).is. A healthy and cordless modern person had nothing to hide (and nowhere to hide). If someone crushed or swore at the recording butterflies that flitted everywhere, people would ask: “What's he got to hide, anyway?” and rumors would begin to circulate.

Indridi and Sigrid lived in an endless apartment block, which wound around the old Coke factory that had been converted into the Puffin Factory. It not only bred puffins for the LoveStar theme park in Oxnadalur but also honey-scented roses. When Indridi opened the window in the morning the house was filled with the fragrance of roses and honey, and “Eat me! Eat me!” sounded from the Puffin Factory across the road and echoed all round the neighborhood.

The Puffin Factory was a gigantic space. The puffins not only had to be on show in the LoveStar theme park up in Oxnadalur, they also had to be conspicuous in the countryside on the way there. Trucks packed with puffins went out daily to distribute them on hillocks along Highway One. They could hardly be bothered to move and so were easy prey for predators, but that did not matter too much as the production cost of each puffin was small compared to the pleasure they afforded passersby.

The Puffin Factory was built following the unprecedented popularity of romantic movies based on Jonas Hallgrimsson's life, which LoveStar had produced at the opening of the Oxnadalur theme park. These were pretty powerful films. People who came to the country afterward had high expectations of being inspired or enthralled and often experienced severe disappointment. According to surveys there were two things that principally got on people's nerves. Firstly, LOVESTAR could not always be seen twinkling over the peaks of LavaRock and, secondly, the birds people saw from the bus window were nothing to write home about. When guides pointed to a puffin and said: “That's a puffin, the bird from the romantic poems, the bird from the romantic movies,” some grumpy voice would always call out from the back of the bus: “

Das ist nicht der Vogel in dem Gedicht. Drichf thef of in fluc!

That ain't the bird I came to see!” And without fail the whole group would chorus the final verse uttered by the poet when his true love had been crushed by an avalanche, the love star had fallen, and the poet had thrown himself in despair from LavaRock:

O, black bird with the rainbow beak

Wings of love and feathers sleek,

So beautiful like babies' hands

Best of birds in all the lands

O, Puffin, sing your song to me

A dream of summer it may be

O, Puffin, will you fly with me?

Will you bring my love to me?

Even as the poet recited this verse, the puffin was flying to him through the snowstorm with a message from his true love in its beak: she had not died in the avalanche but lay trapped in a farmhouse. But just before the puffin reached him, the poet threw himself off LavaRock, and his lover starved to death in the snow.

In the movies about the poet, Wings under the LoveStar and The Boy from Deep Dale, CGI was used to recreate the puffin as it should have looked in the poet's time. The audience gasped with delight as the puffin hurtled through the storm and wept when it fluttered around the poet with the letter as he fell, and even the hardest-hearted were reduced to tears by its mournful song when the poet was crushed on the rocks.

The locals found it desperately humiliating when tourists asked repeatedly: “Oh, is that a guillemot?” Ornithologists (sponsored by a tourist authority interest group) opined that the puffin had repeatedly mated with guillemots or even razorbills or some other such lowly bird. There had been sightings, and photos were published in the papers. And of course there was no way of knowing what the puffins got up to in their overwintering grounds.

It was seen as a symbolic and patriotic act when LoveStar bought up the Coke factory and converted it into a puffin factory. The Puffin Factory scientists worked tirelessly for four years on improvements to the puffin until it would meet the approval of the most exacting tourists. The puffin was as big as a turkey (in fact it was 73 percent turkey, but that was confidential), a strutting and magnificent bird with a rainbow-colored beak. It was utterly delicious, laid brown-splotched eggs, and sang: “Eat me, eat me!”

Every day Indridi walked round the Puffin Factory grounds with a wheelbarrow and rake. He planted cinquefoil and forget-me-nots along the paths, combed out the heather, laid paving stones, and watered the cotton grass in the wetland. He pruned trees, pulled up chickweed, and cut the grass with a scythe. In late summer he picked crowberries and blueberries, took them home, and stirred them into Sigrid's skyr.

On sunny days the inhabitants of the neighborhood strolled through the factory grounds, lay down in the heather, looked up at the clouds, and listened to the song: “Eat me! Eat me!” It was all thanks to LoveStar's ideas and vision.

Indridi and Sigrid's lives had been a dance on honeyed roses for over five years. But suddenly everything had gone to the dogs, and Indridi didn't know whether Sigrid would be waiting for him when he got home. It was a long time since they had stroked their middle fingers together, and it was with heavy steps that he plodded up the stairs. His heart pounded in his chest as he opened the door and called:

“Sigrid? Are you home?”

LOVEDEATH

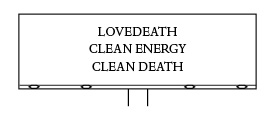

LoveDeath was inextricably linked to love in Indridi and Sigrid's minds. On starlit winter evenings they often drove up to the Blafjoll ski resort just before closing time. When the floodlighting on the slopes was switched off, the most distant stars twinkled. They made themselves comfortable on a mountaintop not far from an iced-over hut half-buried in a snowdrift. On the roof was a billboard:

Indridi and Sigrid stared up into the darkness in silence or amid whispers, listening to their breathing and watching the steam rise from their lips as if from hot springs which sometimes gushed forth. Indridi and Sigrid gushed a lot about life and love as they lay on their backs up in the mountains, watching the twinkling stars and the yellow dome of light in the distance that eternally shielded the city dwellers from darkness and stars.

“There's Orion,” said Indridi.

“There's Capricorn,” said Sigrid.

“Where?” asked Indridi.

“Just below LoveStar,” said Sigrid, pointing to the star that twinkled brightest of all in the sky.

At regular intervals they saw shooting stars. “Someone's just died,” they whispered, watching the flash streak and burn up in the atmosphere, and they were quite right. If they looked it up in the morning paper, they would be able to see who had died and read the obituaries by their loved ones.

When the solar wind was favorable, the Northern Lights would appear, first as thin as an oily film, then dancing and fluttering as if someone had drawn a blue-green brain scan in the sky. The Northern Lights never lasted long. LoveDeath needed the energy. As soon as the lights appeared, there was a bumping and stirring in the hut, a light went on and an old man clambered out. He wore a fur coat and had a big mustache.

“Einar's awake,” whispered Sigrid.

Einar said nothing as a rule. The snow crunched as he walked over to a mast, which stood on the mountaintop, and filled an orange balloon with helium. On it stood written in clear letters:

LOVEDEATH

CLEAN ENERGY

CLEAN DEATH

He tied the balloon to an endless roll of copper wire fastened to the mast, which was in turn connected to a power line that ran directly north to LoveDeath.

“Don't get in the way,” grunted Einar, taking out a knife and cutting the cord that held the balloon.

The wire rattled off the drum at high speed and the balloon shot up into the black night. The Northern Lights had magnified in the meantime. They were like a greeny-white glacial torrent roaring over black sand, while the balloon resembled a float on a line. The old man was fishing, but before Indridi and Sigrid could wonder about the fish, the balloon had reached the right height, the wire grounded the Northern Lights, and a blazing electric river was sucked down the copper wire like a whirlpool down a drain. The mast stood blue as a welding torch in the darkness and the power lines hummed and crackled as the energy surged north along them to LoveDeath. Einar went back into the hut and turned out the light.

Indridi and Sigrid were left behind and watched the balloon glowing like a lightbulb or extra moon with a vortex spiralling around it. They listened to the hum as the energy streamed to earth and watched the odd flash of lightning dart around the wire. Indridi began to think about the float and river again. The old man had emptied the river like the bull in the folktale, while the stars lay like goldfish on the black riverbed. All around they saw balloons popping up from the mountaintops. LoveStar twinkled brighter than ever behind its cloud and a star fell.

“Someone just died,” they both thought as one. Sigrid's eyes brimmed with tears, as it wasn't long since her great-grandmother, Kristoline, had gone the way of all flesh with LoveDeath.

When Kristoline died she was not simply lowered into a cold grave to rot away. Kristoline had been saving up for LoveDeath for a whole decade. Once all sign of life had vanished from the screen, they closed her eyes, and Indridi comforted Sigrid while the old woman was taken by lift down to a branch of LoveDeath in the hospital basement. A woman in a black flight-attendant uniform dressed Kristoline in a silver costume and put her in the black refrigeration unit outside.

The daily yield of the dead was collected from the city at 5:30 pm, and a transport truck thundered north with the bodies, turning left just before the theme park at a road sign that read:

The truck drove into a tunnel at the foot of the mountain and came to a stop in a white-scoured dome. In the middle stood an angled rocket with the words “LoveDeath” printed along its side. The rocket struck an odd note in the polished surroundings, looking fairly battered after countless launches and rough landings on land and sea. The doors of the craft stood open and Kristoline was rolled inside on a conveyor belt along with all the other individuals that the country had yielded that day, in addition to a large crop of Faroe Islanders, Danes, and Norwegians, who had already been loaded on board.

Indridi, Sigrid, and her family took their seats in a gallery on the fifty-seventh floor of the LoveDeath wing of the LoveStar theme park. There was a spectacular view through the glass wall over the glacier, the airships, and the launchpads lined up along the mountain peaks on the western side of the valley. Children ran and bounced cheerfully round the gallery after an exciting day in the company of Larry LoveDeath, a remorselessly cheery bunny in a space suit. A day spent with him helped them gloss over the shock of death. In fact it was so successful that there were few things children found more exciting than LoveDeath: “Great-grandma! When are you going to LoveDeath?” Sigrid's little cousin had asked Kristoline relentlessly in recent years. “My friend's lucky. She's met Larry LoveDeath four times.”

Straggling from the shopping mall with their half-liter bottles of Coke, the teenagers slumped sulkily in the corner, played computer games on their lenses, or hung out on chat lines while their mothers scolded: “Your grandmother is making her grand exit, Magnus dear, will you please pay attention!”

The men got themselves beers at the bar before the big moment arrived and all eyes were fixed on the window. In the bowels of the mountain to the west of the valley the iron doors closed. The hydrogen rocket fuel ignited, and the earth shook as it lifted slowly off the peak before shooting up into the sky on a vast column of fire and smoke. Grieving yet captivated, the crowd watched the rocket swiftly disappearing through the stratosphere and ionosphere until nothing could be seen but a tiny bright light like a daystar. When the light vanished it was clear that old Kristoline had gone beyond the earth's atmosphere. There she and all the other bodies were released into the silent black void where they floated weightless for a single orbit of the earth, but that was not the main event. The magic lay in what came afterward.

The following evening all of Kristoline's descendants drove to the top of Mt. Esja, parked their cars, switched off their headlights, and gazed up into the clear September sky. Sigrid's father scraped frost off the circular view indicator, turned it to synchronize with the time, and peered at the constellation map with his flashlight. Then he looked up and pointed.

“She should appear high up in Ursa Major at eighteen minutes past eleven.”

They all seated themselves on hillocks or rocks or lay on their backs in the soft carpet of moss. Sigrid blew her nose and Indridi put his arms round her. At 11:18 pm Sigrid's great-grandmother began her fall to earth. At that precise moment, at pre-booked coordinates in heaven, gravity exerted its pull and she fell according to Newton's law with accelerating speed, until a long, shining streak of white fire was etched in the silent darkness between the stars. “Shooting star!” whispered the children, and they made a wish. Everything was so poignantly lovely that their eyes filled with tears; death was so symbolic and beautiful. “Life is like a flash in the night,” and the darkness that received death was not empty darkness. It was an infinite black space full of stars, and people were cheered because this was her last and greatest wish: to burn up under the heavenly plough, to fall like a blazing streak against the full moon, to shoot like an arrow from Sagittarius's bow.

As Sigrid's great-grandmother was 70 percent water, it wasn't really possible to say that she had burned to ash. She evaporated. The star became a cloud, and Kristoline was reunited with her fallen husband who was also a cloud, and with all the other millions who had become clouds and rain, which waters the grass and flowers. Bone particles and cell debris fell as an excellent fertilizer for the earth's vegetation. Those who were not used to looking up at the night sky felt dizzy when they saw its unutterable depths and beauty. The mere fact that Kristoline's death united the family and gave them this time up on this mountain under this sky filled them with gratitude:

“Thanks for being born and dying before me and showing me how beautiful the world is and how fragile and short life is. I will never forget you, little great-grandma cloud. I'll take care of my little life and be diligent about saving so I can have myself launched to you when I die.”

Parents pointed up at the sky for the children and said: “Now great-grandma has gone to heaven. She's in the clouds with great-grandpa. If you look at the clouds you might see grandpa's beard or false teeth. If you ask nicely perhaps grandma will make a whale-shape for you, unless they've flown to Africa to make a whale for the children there. You remember how keen they always were on Africa. Tomorrow you must lie on your back and see whether your great-grandma in heaven has made a shape out of the clouds for you.”

It was LoveStar who got the idea for LoveDeath, or rather: the idea got him. The idea wouldn't leave him alone until he had fully realized it. The idea prevented him from sleeping, took away his appetite for food and sex, and pumped him up with chemicals that filled him with so much energy that it had to be born into the world. And although at first some people found the idea for LoveDeath far-fetched, it was actually very simple. The technology already existed: there were thousands of rockets lying around in the old superpower territories, just waiting to be put into service for LoveDeath. And it was no more difficult to launch a rocket in a gale-force blizzard up in Oxnadalur than it was to land a jumbo jet at Keflavik airport in the same conditions. It was all a question of money and marketing, possessing the energy to produce cheap hydrogen, and launching enough rich and famous people to attract the public's attention and create a mood. It was a question of the right man getting the idea. LoveStar did not actually need to know much himself. He had long given up working with his original field of study: the navigation skills and brain functioning of Arctic terns, butterflies, and bees. He didn't need to be an expert in hydrogen, launchpads, astronomy, solar winds, or cloud-drift. This knowledge could be bought. All he needed was the idea, a clear aim, funding, and the power of persuasion to drive a team of people to one goal. He didn't need advice or expensive opinion polls; he felt instinctively what would work and made it work.

The salesmen from LoveDeath's Mood Division sat oozing sympathy at the deathbeds of movie heroes and rock stars. They darkened the wards, turned on their laptops, and projected impressive interactive publicity films.

“LoveDeath will be a brilliant publicity coup for you; it's still so new that the launch will make international headlines. We'll make sure that a clip from your music video will be played during the evening news and, if you're lucky, a greatest hits

CD

will be released all over the world.”

“It was only one song, I only had one hit,” sighed the aged star on his deathbed.

“It'll be re-released. The record sales alone will pay for LoveDeath in a week. You'll make a killing from this. Your name will be immortal. It'll live on among the stars.”

At LoveDeath things were worded the right way and put in the right context. LoveDeath made death cleaner, grander, more glamorous, and simpler. It saved on land area. There was no grave to neglect, no guilt about weeds, no headstone to buy later. No stench, no horror or grinning skulls.