Love at Goon Park (22 page)

Authors: Deborah Blum

“He said, âGet rid of it. You've got to know when to quit.'”

And again, that was it. “He never held it against me and he was rightâyou do have to know when to quit. If you cling to errors, you never learn the right way. It was a very difficult lesson. I was embarrassed and ashamed. But he didn't see it that way. It was that it was over. It was a hard lesson and an important one and I've held onto it.” Rosenblum went on to a heralded career at the State University of New York, directing a behavioral primate laboratory in Brooklyn, and exploring the social development of children.

“Harry never punished you for trying,” Rosenblum continues. “He was at his best, most sympathetic, when you were down. He

never turned his back on people who screwed up.” Harry would even rescue people. Another graduate student, Kenneth Schiltz, had been unable to survive the statistics gauntlet of the psychology department. When Schiltz dropped out, Harry almost immediately gave him a lab job. As many students remember, including Rosenblum, Kenny Schiltz took over the nurturing and the handholding duties at the lab. It might have been difficult to wring overt praise from Harry, but Ken Schiltz loved to tell people that they were doing well. “This lovely man, a defunct ex-grad student of Harry's, stayed with him for years, acting as a drinking companion, a sort of lab manager, researcher, and older brother to the grad students,” Rosenblum says.

never turned his back on people who screwed up.” Harry would even rescue people. Another graduate student, Kenneth Schiltz, had been unable to survive the statistics gauntlet of the psychology department. When Schiltz dropped out, Harry almost immediately gave him a lab job. As many students remember, including Rosenblum, Kenny Schiltz took over the nurturing and the handholding duties at the lab. It might have been difficult to wring overt praise from Harry, but Ken Schiltz loved to tell people that they were doing well. “This lovely man, a defunct ex-grad student of Harry's, stayed with him for years, acting as a drinking companion, a sort of lab manager, researcher, and older brother to the grad students,” Rosenblum says.

And brother is a good word for the relationship because, for Harry, the lab was family. Because it was often his first family, he came to expect his students to see it that way, too. If grad students had children, they often brought them to the lab. Many have memories of babies bundled into blankets and sleeping in offices or the break room. “The first year I was there, I said I can't be at a meeting, I'm going home for Thanksgiving. And Harry just looked at me and said, âYou're going to have to give all that up,'” recalls Lorna Smith Benjamin, now at the University of Utah.

Harry was at his laboratory so much that people started to wonder whether he ever went home. “I mean this kindly; Harry had idiosyncrasies,” said Richard Wolf, a professor of physiology at the University of Wisconsin medical school at the time. Wolf collaborated with Harry on several projects. “Harry believed that you had to be at the lab seven days a week. One Monday morning he came by my lab, and said, âI didn't see you yesterday.'”

Harry took pride in being the man who was always there. He could even be competitive about putting in more time than anyone else. Gene “Jim” Sackett, one of Harry's most valued postdoctoral researchers, used to set his alarm so that he would be the first one at the building. “Harry and I vied for who would open the primate lab. We were both early birds. I would sometimes come in at 5 or 5:30

A.M., and he would come in at 5 or 5:30 A.M., and it would be almost a game, without talking about it, who's going to open the door; because whoever got there first opened the door.”

A.M., and he would come in at 5 or 5:30 A.M., and it would be almost a game, without talking about it, who's going to open the door; because whoever got there first opened the door.”

“You're there at night, he's there at night,” Gluck once wrote in a testimonial to his former professor.

He'd roam the halls at night leaving love poetry on graduate students' desks, checking doors, looking for someone to talk to. He'd invite any comers for a cup of the jet black coffee smoking in the urn by the surgery prep room. He'd invite you in to read a manuscript, where inserted sentences meandered like ant trails around margins and corners. If you couldn't keep up, if he lost interest, he'd just put his head down on his desk, pillowed by his crossed hands.

Questions raced across the mind. Was he asleep? Did I say something that stupid? Do I go on talking? Should I poke him gently to see that he is all right? After a while, you got used to Harry's head going down. It was a message. It meant I'm done with thisâgo back to work.

If that didn't work, he could be even more direct. He'd stick his head into the student break room and interrupt a card game, with a single question. “Making headway?” his tone just sarcastic enough to empty the room. “Do you have an office?” he snapped to one student, who nodded dumbly. “Then go use it.”

Mostly, though, Harry Harlow would just be there, talking to students, the coffee cooling at his elbow and the cigarettes, burning, unnoticed between his fingers, smoke coiling like dreams, the ash glowing redder and redder as it neared his skin. His grad students used to stare, mesmerized, at the imminent collision of hot ash and bare fingers. As with his unfashionable and battered car, his forgotten hats and scarves, he was simply more interested in the conversation or the idea than whatever was in his hand at the moment. Helen LeRoy once tracked Harry down at a scientific meeting by following a trail of partially smoked and smoldering cigarettes. At least he always

dropped them into ashtrays and wastebaskets. One morning, he did that at the lab and the basket burst into flames. LeRoy simply poured her coffee into the fire and put it out. Harry was so busy talking that he never noticed the blaze.

dropped them into ashtrays and wastebaskets. One morning, he did that at the lab and the basket burst into flames. LeRoy simply poured her coffee into the fire and put it out. Harry was so busy talking that he never noticed the blaze.

He seemed to exist on coffee, smoke, and alcohol. He was drinking more than ever by now, not just when he went home but with friends, with students, at local bars and professional meetings. Often, he brought a bottle of liquorâbourbon or scotchâto stock his hotel rooms when he traveled. Of course, in academic psychology, in those days, liquor flowed the way wine does today, only more so. “People don't party now the way they used to,” says William Verplanck, the former Hullian scholar, sadly. “Until the early 1960s, the professional meetings were awash with alcohol. Now if there's a meeting of psychologists, there's a room reserved where people go up to a cash bar.” His voice crackles with disgust and regret for lost times.

“During the thirties, forties, fifties, a university would have a hotel room where people would gather and bring their own bottles or steal somebody else's. There'd be lots of people sitting on the floor in the hall drinking, and talking, and occasionally going back in. Everyone spent some time loaded. Now it's so bloody formal, it's like a meeting of CPAs. We drink less and we communicate less.” Plenty of old colleagues share Verplanck's sense of leaving behind a more exciting time in psychology. “One of my friends insists that it's a waste to die with all your organs intact,” says an old friend of Harry Harlow's, his voice also rich with nostalgia. “We're all so cautious now about what we say and think and do. It used to be a lot more interestingâand more fun. It was a spicier time.”

Harry's habits suited that time of smoke and drink and rapid-fire conversation perfectly. In some ways, he surpassed it. Alcohol was becoming an integral part of his life. He even wrote odes to it:

Clover club's a nice girl / Vodka is a shrew / Corn whiskey is the old love / Scotch whiskey is the new.

When he was burned out at the lab, he liked to take an early evening walk down to a nearby tavern. “You knew you'd arrived when Harry asked you to go for a walk,” Zimmermann

said. “Harry'd come in, pick someone out, and say, âLet's go for a walk.' You'd usually go for a beer, sit down, and sometimes he'd talk and sometimes he'd never say a word. I remember I got there in July and September was my first walk. That was a thrill. We went to this bar, and ordered a beer, and he said, âGot a dollar?'”

Clover club's a nice girl / Vodka is a shrew / Corn whiskey is the old love / Scotch whiskey is the new.

When he was burned out at the lab, he liked to take an early evening walk down to a nearby tavern. “You knew you'd arrived when Harry asked you to go for a walk,” Zimmermann

said. “Harry'd come in, pick someone out, and say, âLet's go for a walk.' You'd usually go for a beer, sit down, and sometimes he'd talk and sometimes he'd never say a word. I remember I got there in July and September was my first walk. That was a thrill. We went to this bar, and ordered a beer, and he said, âGot a dollar?'”

It still makes Zimmermann laugh.

“He called me Jim, which surprised me because he mostly called people by their last names,” recalls Jim Sackett, now a professor of psychology at the University of Washington in Seattle. Sackett occasionally worried that Harry Harlow would just burn up on alcohol fumes and psychology dreams. “He'd say, âJim, let's go to the corner.' So we'd go the bar on the corner. By the time we'd left, he'd had three, four drinks. I'd had one. And I'd drive him home and think, âGod, he's gonna die, he's just out of it. He's gonna be dead.' The next morning he'd be there at 5 A.M. He'd be there and he'd be writing.”

And it was during those hyperactive, free-form, sleep-deprived, alcohol-inspired days that Harry Harlow first started thinking about the nature of love. That he got there at all can seem improbable. You could make a case that this was the least likely laboratory to take on the cause of love, this outpost of Wisconsin psychology where work came first and family last. You could argue that Harry would be the most unlikely of champions, a man whose world turned on monkeys and primate labs and graduate students arguing their theories over coffee and cards and nights at the corner bar. He was a father who left the house before his children were awake, a man trailing a failed marriage behind him. He was sarcastic, edgy, and completely opposed to sentiment.

You could also make the case that Harry Harlow was absolutely perfect for the jobâa man objective enough about love to see it as the stuff of science. A psychologist who still allowed for all the possibilities. He was a scientist with a love of the creative, a professor willing to give his students every chance to let their ideas take flight; a man who still wrote poetry in the night, who supported young

researchers who didn't agree with him. He was a man who could laugh at his own mistakes. The hard times had helped make him a psychologist who didn't worry about fitting in or making the right impression. They hadn't stopped him from being a dreamer, though, or a lover of lost causes or a man who could look at a lab full of burly, quarrelsome rhesus macaques and start thinking about the importance of mothers and the needs of children.

researchers who didn't agree with him. He was a man who could laugh at his own mistakes. The hard times had helped make him a psychologist who didn't worry about fitting in or making the right impression. They hadn't stopped him from being a dreamer, though, or a lover of lost causes or a man who could look at a lab full of burly, quarrelsome rhesus macaques and start thinking about the importance of mothers and the needs of children.

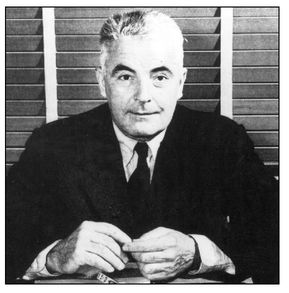

Psychologist B.F. Skinner of Harvard University, perhaps the most famous advocate of conditioned behavior in both animals and humans.

Photo courtesy of the Archives of the History of American Psychology

Photo courtesy of the Archives of the History of American Psychology

John B. Watson, shortly after the publication of his best-selling book,

The Psychological Care of the Child and Infant

, which warned parents not to treat their children with obvious affection.

Photo courtesy of the Archives of the History of American Psychology

The Psychological Care of the Child and Infant

, which warned parents not to treat their children with obvious affection.

Photo courtesy of the Archives of the History of American Psychology

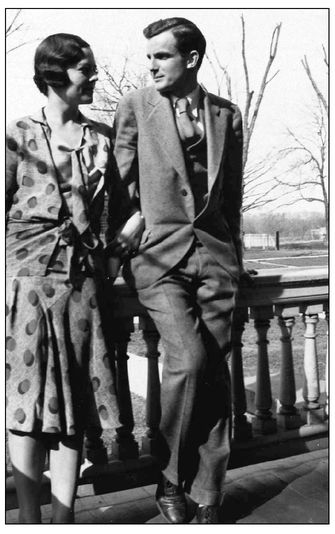

Clara Mears and Harry Harlow in 1931, in the happy year before their first marriage to each other.

Photo courtesy of Robert Israel

Photo courtesy of Robert Israel

Other books

Mr. Unlucky by BA Tortuga

The Kings Man by Rowena Cory Daniells

Brainrush 05 - Everlast 02: Ephemeral by Bard, Richard

IGMS Issue 50 by IGMS

Gerda Malaperis by Claude Piron

Moving Day by Meg Cabot

The Seraphina Donavan Collection: Contemporary by Donavan, Seraphina

Chimes from a Deeper Sea by M P Ericson

One Hundred & Thirty-Six Scars (The Devil's Own, #1) by Jones, Amo