Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (13 page)

Read Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book Online

Authors: Walker Percy

Tags: #Humor, #Essays, #Semiotics

(a)

Self as Immanent. The self sees itself as an immanent being in the world, existing in a mode of being often conceived on the model of organism-in-an-environment as a consequence of the powerful credentials of science and technology.

Such immanence is a continuum. At one end: the compliant role-player and consumer and holder of a meaningless job, the anonymous “one”—German

man

—in a mass society, whether a backfence gossip

*

or an Archie Bunker beer-drinking TV-watcher.

At the other end: the “autonomous self,” who is savvy to all the techniques of society and appropriates them according to his or her discriminating tastes, whether it be learning “parenting skills,” consciousness-raising, consumer advocacy, political activism liberal or conservative, saving whales, TM, TA, ACLU, New Right, square-dancing, creative cooking, moving out to country, moving back to central city, etc.

The self is still problematical to itself, but it solves its predicament of placement vis-à-vis the world either by a passive consumership or by a discriminating transaction with the world and with informed interactions with other selves.

(b)

Self as Transcendent. In a post-religious age, the only transcendence open to the self is self-transcendence,

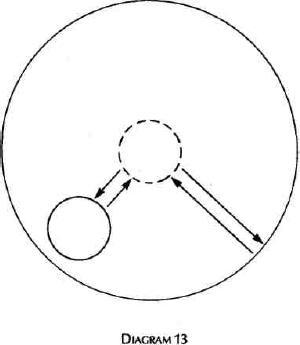

The Immanent Self feeling somewhat Problematical and therefore staking everything on Interactions with other Selves and with the World

Interactions with other selves: more or less successful; that is, at one pole, exploitative, manipulative, etc.; at other pole, caring, creative, imaginative, venturesome, etc.

Interaction with world: more or less successful; that is, at one pole, passive consumership of TV, food, drugs, etc.; at other pole, discriminating consumership of do-it-yourself hobbies, participatory sports, gourmet cooking, off-beaten-track travel to Katmandu, etc.

that is, the transcending of the world by the self. The available modes of transcendence in such an age are science and art.

(i)

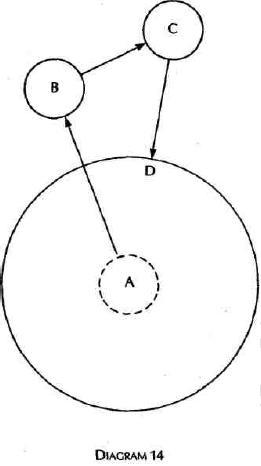

Transcendence by Science. The scientist is the prince and sovereign of the age. His transcendence of the world is genuine. That is to say, he stands in a posture of objectivity over against the world, a world which he sees as a series of specimens or exemplars, and interactions, energy exchanges, secondary causes—in a word: dyadic events. (See

diagram 14

The problematical self, like the young Einstein who couldn’t stand the dreariness of everyday life, discovers science and transcends the world. In orbit, he enters an elect community of other scientists, however small, to whom he can address sentences about the world.

The scientist, though transcendent and “in orbit” around the ordinary world, has minimal problems with reentry. That is to say, he is able to maintain a more or less stable orbit so that in ordinary intercourse he is generally seen as no more than “absentminded,” like Einstein, who thought for twenty years about his general theory, and von Frisch, who pondered bee communication for forty years.

Reentry problems become noticeable in less inspired scientists. The divorced wife of an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory accused her husband of “angelism-bestialism.” He was so absorbed in his work, the search for the quasar with the greatest red shift, that when he came home to his pleasant subdivision house, he seemed to take his pleasure like a god descending from Olympus into the world of mortals, ate heartily, had frequent intercourse with his wife, watched TV, read Mickey Spillane, and said not a word to wife or children.

But at the peak periods of scientific transcendence, he, the scientist, becomes the secular saint of the age: Einstein is still referred to as a benign deity.

With the waning of transcendence, reentry problems increase. One manifestation, which always amazes laymen, is the jealousy and lack of scruple of scientists. Their anxiety to receive credit often seems more appropriate to used-car salesmen than to a transcending community.

Other examples of reentry failures: the general fatuity of scientists in political matters, their naïveté and credulity before tricksters. The magician Randi says that scientists are easier to fool—e.g., by Uri Geller—than are children.

More distressing consequences occur when the zeal and excitement of a scientific community runs counter to the interests of the world community, e.g., when scientists at Los Alamos did not oppose the bomb drop over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The joys of science and the joys of life as a human are not necessarily convergent. As Freeman Dyson put it, the “sin” of the scientists at Los Alamos was not that they made the bomb but that they enjoyed it so much.

How the Problematical Self can Escape its Predicament by Science

AB = The problematical self, finding itself in a disappointing world and in all manner of difficult relationships, escapes by joining the scientific community, either by becoming a scientist or by understanding science.

BC = The transcending community of scientists.

CD = From the perspective of BC, the world can now be seen by A triumphantly as a dyadic system.

(ii)

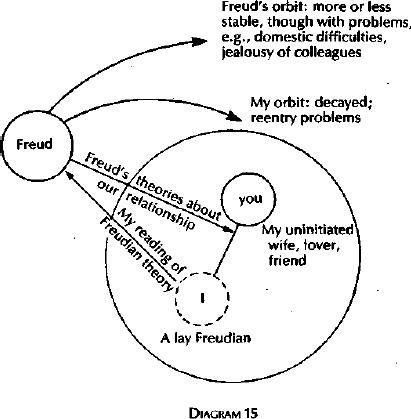

Decayed Orbits of Transcendence. The layman can in some cases participate in the transcendent community of science, but often at a price.

Consider a familiar example, the lay Freudian, that is, the avid reader and disciple of Freud who does, to a degree, share in the excitement of Freud’s insights but whose excitement all too often derives not from a shared discovery but from the sense of election to an elite from which vantage point one can play a one-upmanship game with ordinary folk: “What you say is not really what you mean. What you really mean, whether you know it or not, is—”

Their impoverishment is to be located in both an inflation of theory and a devaluation of the world theorized about. They out-Freud Freud without the scruples of Freud.

Yet they, the lay scientists, those who perceive themselves in the community of scientists and at some remove from the ordinary world, may be better off than those who live immanent lives, beneficiaries of science and technology, but with only a glimmering of the scientists, the glimmering that there are scientists and that “they” know about every sector of the world, including one’s very self. “They” not only know about the Cosmos, they know about me, my aches and pains, my brain functions, even my neuroses. A remarkable feature of the secondhand knowledge of scientific transcendence is the attribution of omniscience to “them.” “They” know.

The Decayed Orbit of the Lay Freudian

or, How it is one thing to be Freud and to spend a life inducing a remarkable theory from the endlessly complex manifold of human phenomena and, How it is something else to read some Freud, master a few principles, return to the ordinary world and human relationships with the sense that you alone are privy to the hidden mechanisms of these relationships. Such reentries can be disastrous for both parties, Freudian and non-Freudian.

They are expected to know. Example: a recent Donahue Show in which paraplegics discussed their troubles. The message: rage at doctors. “They” could cure us if they wanted to, took the time, did their research. The powers attributed to

them,

the scientists—powers which they, the scientists, never claimed—are as magical as those of the old gods.

The layman, dazzled by the extraordinary accomplishments of science and technology, nevertheless gives away too much to science. Where the genuine scientist is generally amazed at the meagerness of knowledge in his own field, the layman is apt to assign omniscience as what he takes to be a property of scientific transcendence.

(iii)

Transcendence by Art. If the scientist is the prince of the post-religious age, lord and sovereign of the Cosmos itself through his transcendence of it, the artist is the suffering servant of the age, who, through his own transcendence and his naming of the predicaments of the self, becomes rescuer and savior not merely to his fellow artists but to his fellow sufferers. Like the scientists, he transcends in his use of signs. Unlike the scientists, he speaks not merely to a small community of fellow artists but to the world of men who understand him.

It is no accident that, for the past hundred years or so, the artist (poet, novelist, painter, dramatist) has registered a dissent from the modern proposition that, with the advance of science and technology, man’s lot will improve in direct proportion. The alienation of the artist puzzles many, both the scientists and technologists who are happy and busy and their lay beneficiaries who are happy in the immanence of consumption. Most Danes and Japanese don’t appear to be alienated—though there are those who say that their obliviousness of their own immanence is the worst alienation of all. To most of the happy von Frisches and Rutherfords and to the contented denizens of Silicon Valley, the dark views of modern life held by most serious novelists since Tolstoy, most poets since Tennyson, most painters since Millet, most dramatists since Schiller, have seemed neurotic indulgences. It is possible, however, that the artist is both thin-skinned and prophetic and, like the canary lowered into the mine shaft to test the air, has caught a whiff of something lethal. Indeed, as this dreadful century wears on, even the most immanent Dane and the most proficient IBM computer-engineer is beginning to sense that all is not well, that the self can be as desperately stranded in the transcendence of theory as in the immanence of consumption.

The artist, caught in the predicament of the self, is at once more vulnerable to the predicament of self than the nonartist and at the same time privileged to escape it by the transcendence of his art. He serves others who share his predicament by naming it.

The difference between Einstein and Kafka, both sons of middle-class middle-European families, both of whom found life in the ordinary world intolerably dreary:

Einstein escaped the world by science, that is, by transcending not only the world but the Cosmos itself.

Kafka also escaped his predicament—occasionally—not by science but by art, that is, by

seeing

and naming what had heretofore been unspeakable, the predicament of the self in the modern world.

The salvation of art derives in the best of modern times from a celebration of the triumph of the autonomous self—as in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—and in the worst of times from naming the unspeakable: the strange and feckless movements of the self trying to escape itself.

Exhilaration comes from naming the unnameable and hearing it named.

If Kafka’s

Metamorphosis

is presently a more accurate account of the self than Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, it is the more exhilarating for being so.

The naming of the predicament of the self by art is its reversal. Hence the salvific effect of art. Through art, the predicament of self becomes not only speakable but laughable. Helen Keller and any two-year-old and Kafka’s friends laughed when the unnameable was named. Kafka and his friends laughed when he read his stories to them.