Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (12 page)

Read Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book Online

Authors: Walker Percy

Tags: #Humor, #Essays, #Semiotics

Slimy

does not sound slimy to a German speaker.

IX

Signs undergo an evolution, or rather a devolution.

*

At first, the signifier serves as the discovery vehicle through which the signified is known, e.g., Helen Keller discovering water through

water

—or any two-year-old learning the name of a new object—Peirce’s example:

B

OY:

What is that?

F

ATHER:

That is a balloon.

Note that when a child hears a new name, he will repeat it; his lips will move silently while he frowns and muses as he considers

how

this round inflated object can be fitted into this peculiar utterance,

balloon.

Next, the signifier becomes transformed by the signified: the signifier

balloon

becomes informed by the distention, the stretched-rubber, light, uptending, squinch-sound-against-fingers signified.

Next, there is a hardening and closure of the signifier, so that in the end the signified becomes encased in a simulacrum like a mummy in a mummy case.

F

IRST BIRD WATCHER:

What is that?

S

ECOND BIRD WATCHER:

That is only a sparrow.

A devaluation has occurred. The bird itself has disappeared into the sarcophagus of its sign. The unique living creature is assigned to its class of signs, a second-class mummy in the basement collection of mummy cases.

But a recovery is possible. The signified can be recovered from the ossified signifier, sparrow from

sparrow.

A sparrow can be recovered under conditions of catastrophe.

The German soldier in

All Quiet on the Western Front

could see an ordinary butterfly as a creature of immense beauty and value in the trenches of the Somme.

A poet can wrench signifier out of context and exhibit it in all its queerness and splendor.

*

Cézanne recovered apples from the commonplace sign,

apples.

Scientists recover the inexhaustible mystery of the signified from the mundane closed-off simulacrum of the world-sign.

One sees a line of ants crossing the sidewalk and sees it as—

ants crossing the sidewalk.

Fabre saw ants crossing the sidewalk and stopped to wonder where they came from, where they were going, how they knew how to get there, and why. Then, like von Frisch and his bees, he discovered there is no end to the mystery of ants.

X

Consciousness:

Conscious

from

conscio,

I know with.

Consciousness is that act of attention to something under the auspices of its sign, an act which is social in its origin. What Descartes did not know: no such isolated individual as he described can be conscious.

It is no etymological accident that the prefix

con-

is part of the word, since the origin of consciousness is the initiation of the sign-user into the world of signs by a sign-giver.

It is also not an accident that grammatical usage requires that

conscious

and

consciousness

are generally followed by

of.

One is always conscious

of

something.

It is also the case that one is always conscious

of

something

as

something—its sign.

If a hunter is conscious of an animal in the field, it is part of the act of consciousness to

place

it—as a rabbit, fox, deer. The signing process tends to configure segments of the Cosmos under the auspices of a sign, often mistakenly. It is often possible to

see

a certain pattern of light and shadow

as

a rabbit, ears, and all. The hunter coming closer may say with surprise: “I thought it was a rabbit.”

Deer hunters, who are increasingly shooting each other more often than deer, invariably report: “But I

saw

a deer!”

XI

If the sign-user first enters into an Edenic state by virtue of his discovery and constitution of the world by signs, like Helen Keller or any normal two-year-old, and if aboriginal sign-use is a joyful concelebration of the world through an utterance in which the ancient environment of the Cosmos is transformed and beheld in common through the magic prism of the sign, it is also, semiotically speaking, an Eden which harbors its own semiotic snake in the grass.

The fateful flaw of human semiotics is this: that of all the objects in the entire Cosmos which the sign-user can apprehend through the conjoining of signifier and signified (word uttered and thing beheld), there is one which forever escapes his comprehension—and that is the sign-user himself.

Semiotically, the self is literally unspeakable to itself. One cannot speak or hear a word which signifies oneself, as one can speak or hear a word signifying anything else, e.g.,

apple, Canada, 7-Up.

The self of the sign-user can never be grasped, because, once the self locates itself at the dead center of its world, there is no signified to which a signifier can be joined to make a sign. The self has no sign of itself. No signifier applies. All signifiers apply equally.

You are

Ralph

to me and I am

Walker

to you, but you are not

Ralph

to you and I am not

Walker

to me. (Have you ever wondered why the Ralphs you know look as if they ought to be called Ralph and not Robert?)

For me, certain signifiers fit you, and not others. For me, all signifiers fit me, one as well as another. I am rascal, hero, craven, brave, treacherous, loyal, at once the secret hero and asshole of the Cosmos.

You are not a sign in your world. Unlike the other signifiers in your world which form more or less stable units with the perceived world-things they signify, the signifier of yourself is mobile, freed up, and operating on a sliding semiotic scale from –α to α.

The signified of the self is semiotically loose and caroms around the Cosmos like an unguided missile.

From the moment the signifying self turned inward and became conscious of itself, trouble began as the sparks flew up.

No one knows how such a state of affairs came to pass, except through the wisdom (or folly) of religion and myth.

*

But, semiotically speaking, it is possible to describe the consequences.

As a consequence of the unprecedented appearance of the triad in the Cosmos, there appeared for the first time in fifteen billion years (as far as we know) a creature which is ashamed of itself and which seeks cover in myriad disguises.

One semioticist defined the subject of his study as the only organism which tells lies.

The exile from Eden is, semiotically, the banishment of the self-conscious self from its own world of signs.

The banquet is still there, but it is Banquo in attendance.

The self perceives itself as naked. Every self is ashamed of itself.

The semiotic history of this creature thereafter could be written in terms of the successive attempts, both heroic and absurd, of the signifying creature to escape its nakedness and to find a permanent semiotic habiliment for itself—often by identifying itself with other creatures in its world.

Among Alaskan Indians, this practice is called totemism. In the Western world, it is called role-modeling.

The question must arise: What is the nature of the catastrophe of the self? Is the catastrophe nothing more or less than the breakthrough itself, the sudden emergence of the triadic organism into a dyadic world? And is the predicament of the self the price of naming and knowing? Or is the catastrophe a subsequent event, a bad move in the exercise of its freedom by the sign-user? Is it a turning from the concelebration of the world to a solitary absorption with self?

It is fruitful to speculate on the possible nature of other intelligences (ETIs) in the Cosmos, if they exist.

Presumably, they too have achieved the triadic breakthrough. Might they not have achieved the world of signs without succumbing to the terrible penalty? Might there not exist preternatural intelligences who do not necessarily share the shadow-life of the earth-self?

Much of current speculation about the nature of ETIs— what level of technology have you achieved?, etc.—is misguided. The first question an earthling should ask of an ETI is not: What is the level of your science? but rather: Did it also happen to you? Do you have a self? If so, how do you handle it? Did you suffer a catastrophe?

XII

As soon as the self becomes self-conscious—that is, aware of its own unique unformulability in its world of signs—from that moment forward, it cannot escape the predicament of its placement in the world.

An organism exists in its environment in only one mode, that of an open system responding to those segments of its environment to which it is genetically programmed to respond or to which it has learned to respond.

But a self must be

placed

in a world. It cannot

not

be placed. If it chooses by default not to be placed, then its placement is that of not choosing to be placed.

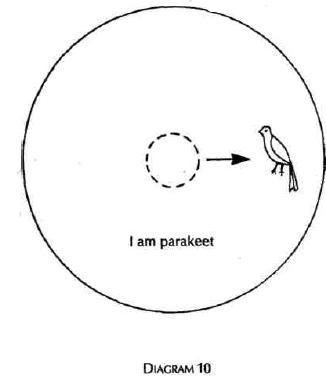

Some Traditional Modes of Self-Placement:

(a)

Totemistic.

The self, here drawn as a dotted circle because it is problematical to itself, finds its identity in one or another of the resplendent signs of its world, especially those possessed of those qualities most admired by the self: animals, trees, clouds, thunder, sky, falcon.

Q

UESTION:

What are you?

A

LEUT INDIAN:

I am bear.

Q

UESTION:

What are you?

M

OVIE ACTRESS:

I’m a Leo.

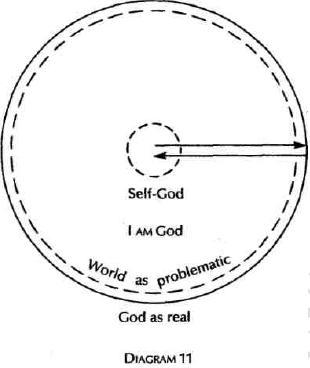

(b)

Eastern Pantheistic. The self is identified with God, the God which is everywhere in the world, including one’s self, yet behind the illusory appearances of world-signs. Therefore, God is to be found in the true depths of the self.

Both the world and the self are problematical. The self becomes itself by identifying with God, who is found both in one’s self and behind the

maya

of the world.

Who are you?

I am

Atman,

which is to say God in myself, but also

Brahman,

the God of the Cosmos.

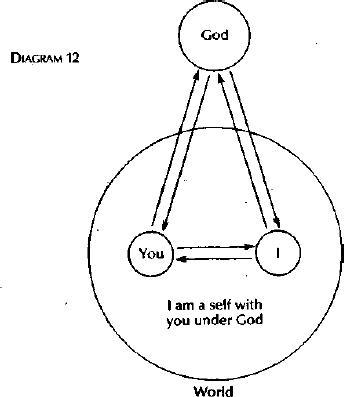

(c)

Theistic-historical (Judaism, Christianity, Islam). The self becomes itself by recognizing God as a spirit, creator of the Cosmos and therefore of one’s self as a creature, a wounded creature but a creature nonetheless, who shares with a community of like creatures the belief that God transcends the entire Cosmos and has actually entered human history—or will enter it—in order to redeem man from the catastrophe which has overtaken his self.

XIII

In a post-religious technological society, these traditional resources of the self are no longer available, leaving in general only the two options: self conceived as immanent, consumer of the techniques, goods, and services of society; or as transcendent, a member of the transcending community of science and art.