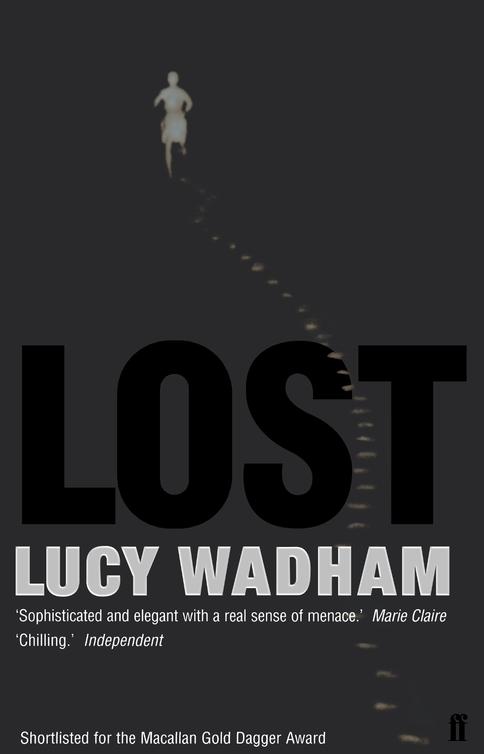

Lost

Authors: Lucy Wadham

Lucy Wadham

for

my

children,

Felix

and

Lily

- Title Page

- Dedication

-

- Prologue

- Chapter One

- Sunday

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Monday

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Tuesday

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- Chapter Twenty-Three

- Wednesday

- Chapter Twenty-Four

- Chapter Twenty-Five

- Chapter Twenty-Six

- Chapter Twenty-Seven

- Thursday

- Chapter Twenty-Eight

- Chapter Twenty-Nine

- Friday

- Chapter Thirty

- Chapter Thirty-One

- Chapter Thirty-Two

- Chapter Thirty-Three

- Chapter Thirty-Four

- Chapter Thirty-Five

- Chapter Thirty-Six

- Chapter Thirty-Seven

- Chapter Thirty-Eight

- Chapter Thirty-Nine

- Chapter Forty

- Epilogue

-

- About the Author

- Copyright

Mickey da Cruz sits, his great barrelled torso tipped forward, his elbows resting on his knees, his little hands clasped between his legs. Out of his good eye he watches the swing doors of the cafeteria letting people in and out like a valve, while his weak eye keeps sliding towards his temple, his own private stress signal: their plane is late.

A young woman in an Avis uniform walks up to the bar ahead of him, drops her bag at her feet and slides her arse on to the stool. Behind her, like a reprimand, comes a priest wearing a black soutane buttoned to the floor. Mickey thinks he sees the priest slowing at the space beside the woman, then passing on to settle two places further along.

Mickey leans back and takes his cigarettes from his pocket. He lifts the soft packet to his lips and pulls one out with his teeth: you never know, the Avis woman might have eyes in the back of her head. He can see from the way the priest is counting out the change for his coffee that he is a foreigner; probably Italian, like the two brothers waiting for him in the car park. But there are Italians and Italians, and Mickey knows that the Scatti brothers are the scum.

The plane comes in with a sound like wind in a tunnel and he drops his cigarette, stands up, and turns to look through the plate glass at the runway. People begin to move towards the windows to watch, the men holding their suit jackets over their shoulders. Mickey squeezes the tiny camera in his pocket. It has cost him his savings, but he believes that he will not regret the investment. With it he has the opportunity to show everyone how elaborate his mind can be. When they are still reeling he will be on his way out of here for ever.

Through the plate glass he hears the engines moan as they

slow and stop. He keeps his good eye on the door at the front of the plane. The stairs are long in coming and his anxiety grows as he watches the driver dicking around with his manoeuvre. At last the first passengers step out into the kerosene haze. His eye is aching from watching the stairs and then he spots her, on the ground, moving quickly on the outside of the crowd. Her shape is distorted for a moment by a fault in the plate glass in front of him or the heat rising from the tarmac, he is unsure which. He shifts and she is righted again. She is overtaking the other passengers making their way towards the terminal entrance beneath him. As she draws nearer, he can see the mass at her side is a bag with a coat draped over it. And there are her boys, behind and to either side of her, running to keep up. The elder seems to be wearing a pair of strange spectacles and the younger is clutching a piece of her dress.

Mickey pushes through the swing doors and runs down the stairs. He takes up his position in the blind spot to the left of the arrivals gate where the first passengers are coming through at a shuffle. The woman is tall and holds her chin up as if to drive the point home. Her arms are long and sinewy, not his idea of how a woman’s limbs should be. And here is the child, the heir, smaller than he had imagined, his yellow rucksack bouncing on his back with each step. The glasses are swimming goggles. Now the mother is passing him, so close he could reach out and touch her. He follows them to the arrivals hall. The woman’s hair sways in one dark block from side to side. She stands still and leans down to hear what her youngest son is saying, holding her hair away from her face. The boy reaches up and locks his hands around her neck, and she straightens, gathering him up, placing him on her hip and moving straight on in one movement so graceful he suddenly feels cold inside, as though a draught were blowing on his entrails.

As she waits for her luggage, the younger child still in her arms, he smokes another cigarette to settle himself. He notices

how she watches the other passengers waiting. She is watching the little flutter of aggression as the moment approaches to grab their possessions and haul them on to the trolley they have fought for. Her eldest is circling her in ever wider orbits. Mickey watches her mother’s radar blinking on and off. He can now feel the adrenaline running to his finger-ends and his heart is booming in his oversized thorax, his body in revolt as he sets himself against the wisdom of the island. He breathes the smoke in deeply. When at last he treads on his cigarette and follows her out into the hot afternoon, he knows he is ready.

They cross a strip of grass watered by sprinklers. The boys run back and forth through the hanging mist, but she does not wait for them and they tear themselves away and out again with her into the white sunlight that bounces off the road. Mickey turns and walks back to the car, keeping her in sight.

He sits in the driver’s seat, the Scattis in the back as if he is their chauffeur. The three of them wait with the windows up, the air-conditioning humming. They watch the mother in silence as she emerges from the Hertz cabin. She throws the two bags and the rucksack into the boot and her handbag in through the driver’s door. They can see her irritation as the elder boy fools around. When at last he climbs in she slams the door hard behind him.

She drives fast, hardly braking on the sharp turns that lead up into the mountains. Mickey opens the window to smoke and swears at her in admiration out of the corner of his mouth: ‘

Putain

,’ he says. ‘

La garce

.’

In the back the brothers sit side by side, each looking out of his own tinted window, in their dour, foreign silence.

As they drove past the playground at the entrance to the village of Santarosa, Sam pulled off his swimming goggles, twisting his head round to get a better look.

‘Sit down.’

His mother’s arm came up in front of him like a barrier. He glanced at her, then turned round again to look through the dust wake of the car at the deserted playground.

‘Sit down, Sam. Please.’

Dan was asleep in the back, his hair glued to his forehead with sweat. Sam picked a crisp off the seat and ate it.

‘I said please.’

He faced forward.

‘Can we go to the beach?’

She looked at him. Her eyes told him she was not in a good mood.

‘Sam. Not now.’

She glanced at Dan in the mirror.

‘How fast does a scorpion run? Does it go faster than a snake? Which is faster?’

‘I’ve no idea.’

‘Come on.’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Just say what you think.’

‘You want me to make up an answer? What’s the point?’

‘No, but just tell me what you think. The scorpion or the snake?’

‘The snake.’

‘Why?’

‘It’s bigger and it has more muscles. Look, we’re here.’

Sam raised himself on his hands and looked out at the

main square. There were three old people, a man and two women, sitting on the fountain. His mother always made him kiss the old people in the village, one by one, four times each. That made twelve. As they drove past he slid down in his seat.

His mother was trying to turn into the very narrow street that led up to the big house, but she was not managing. The car was too big to turn. He watched her changing gear, forward and back, forward and back, her silver bracelets clinking on her arm and her forehead worried as she looked in the mirror. He opened his window.

‘How much can you drink before you explode?’

‘Just be quiet.’ She changed gear and the engine made a grinding noise.

Sam turned, took another crisp from the back seat and heard the car scraping along the wall on his mother’s side.

‘You’ve scraped the car.’

She jerked the car back and then climbed out. Sam turned and looked at his brother’s sleeping face. He was dribbling out of the side of his mouth. Sam reached out and touched his red cheek.

‘Leave him!’ his mother hissed. She was at his window.

Then he remembered: ‘My fish!’

‘Oh, Sam. You didn’t bring it.’

He opened the door, pushed past her and ran to the boot.

‘Quick, Mummy.’

She opened the boot for him and he pulled out his rucksack. It was dripping.

‘I told you not to bring him.’

Sam dropped to his knees and unzipped the yellow rucksack. He felt inside and took out the Tupperware box, which had emptied of water, then tipped out the contents on to the road. His goldfish lay unnaturally straight among his plastic men. He picked up the fish and held it on his palm, feeling the softness of it and the coldness, and he looked at its open mouth, and his own throat dried up.

‘It’s all right, Sam. He’s not dead.’

She took the fish from him and was gone. He watched her disappear into the Hôtel Napoléon on the other side of the square. She was gone too long, and he sat there staring at his plastic men lying stupidly on the ground and tried not to cry. Then she was there, holding out a glass of water, and they looked into it at his fish lying on the rotating surface, dead as dead could be.