LOSING CONTROL (21 page)

Authors: Stephen D. King

There are significant problems with this approach.

Smuggling and other cross-border criminal activities will rise.

The domestic suppliers may not receive the higher global price for their endeavours, reducing their incentive to produce more food.

And other countries can easily retaliate.

Nevertheless, as with energy supplies, the producers of food – particularly basics such as grain – may increasingly have the upper hand.

That’s good news for major emerging-market rice exporters such as Thailand, India, Vietnam, Pakistan and China but not quite so encouraging for major rice importers such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Nigeria and Bangladesh.

15

Could the food-producing nations unleash their own brand of state capitalism on the food-consuming nations?

With climate change, might food wars also develop into water wars?

And could this provide the opportunity for Western powers to adopt a ‘divide and rule’ strategy towards the emerging world?

With the US willing to share its nuclear technologies with the Arab Gulf States (which are not short of energy) and India (to provide a counterweight to China), one can envisage the development of series

of regional ‘Cold Wars’ sponsored by the West in a bid to maintain the status quo.

State capitalism is on the rise because sleeping giants are awakening.

Those sleeping giants have hitherto been unable to make a major claim on the world’s raw materials because they have been too poor, too disconnected or too dogmatically attached to a defunct political philosophy.

Yet all this is now changing.

Russia has its gas, China and India have their cheap labour and Brazil has its commodities.

They increasingly have incentives to strike deals with each other.

They hope, after all, to continue to grow rapidly in the years ahead.

They know that energy and food may be increasingly in short supply as the Malthusian calculus threatens to catch up with earlier productivity gains.

And they also know that the economic success of the developed world over the last few hundred years depended not just on the triumph of the market but also on the protection of infant industries, the exploitation of virgin lands and the willingness to use military intervention to safeguard economic interests.

The British East India Company paved the way for all that followed.

We’re not really seeing the rise of state capitalism but, instead, its return.

And, as it returns, so the developed world’s hold on the levers of economic power is slipping away year by year.

RUNNING OUT OF WORKERS

DEMOGRAPHIC DYNAMICS

The developed world is running out of workers.

Most of the emerging world is not in the same position, at least not yet.

The baby boomers who flooded Western and Japanese labour markets in the 1970s and 1980s are now heading into retirement.

They’re expecting someone, somewhere, to look after them.

People in the developed world are about to become economically dependent on workers in the emerging world.

We’ve been here before, of course.

As I argued in Chapter 2, Europe and its offshoots in the Americas and Australia would never have made so much progress over the last five hundred years without the use of an ‘emerging’ labour supply.

This, however, was a world of slavery and indentured servitude which, one hopes, will not be making a comeback any time soon.

1

The developed world finds itself, once again, relying on the efforts of other, poorer, people.

This time, coercion of individual workers is

unacceptable (or, at the very least, is hidden from view).

If people in the developed world are to live happily in their retirements, they will have to stake a credible claim on the world’s scarce resources through market mechanisms or through the power of their nation states to influence regimes elsewhere.

Population numbers ebb and flow through three main biological influences: the fertility rate (the number of children per woman), the infant mortality rate and adult life expectancy.

2

Population ‘explosions’ typically occur when there is a decline in infant mortality and a rise in adult life expectancy and only a lagged reduction in fertility.

Infant mortality rates in the UK dropped significantly from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, helped by public-health programmes such as the Vaccination Act of 1871.

Life expectancy for British males rose from around forty in the mid-nineteenth century to about fifty by the time of Queen Victoria’s death in 1901.

Fertility rates adjusted much more slowly.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, a typical Englishwoman would have five children.

Queen Victoria herself managed nine (she might have had more had Prince Albert not succumbed to typhoid fever in 1861).

Over the following fifty years, the fertility rate declined only modestly.

With the arrival of Edwardian England, the typical woman of childbearing age was still giving birth to four children.

Only by the middle of the twentieth century had the fertility rate dropped to around two, a number recognizable today.

Shortly afterwards, there was a temporary boost back up to about 2.7 as post-war baby boomers popped out, apparently in response to a surge in optimism in the 1950s and early 1960s.

3

According to the 1801 census, the population of England at the beginning of the nineteenth century stood at 8.3 million.

By 1851, the population had risen to 16.8 million, before doubling again to 30.5

million in 1901, a rise of 267 per cent in a single century, implying an average annual growth rate of 1.3 per cent.

A hundred years later, in 2001, the population of England had risen to 49.1 million, a further 61 per cent increase at an annual rate of increase of 0.5 per cent.

Population growth slowed in the twentieth century primarily because of a more sustained fall in the fertility rate: life expectancy continued to rise and infant mortality rates carried on dropping.

England’s experience in the nineteenth century was matched by countries in East Asia in the second half of the twentieth century, although the transformation in China, Japan and Korea was much quicker.

From the 1950s through to the end of the 1960s, the East Asian fertility rate averaged around five.

Life expectancy, however, rose rapidly, from a remarkably low forty-three in the early 1950s to sixty-four in the early 1970s and around seventy-five in the early years of the twenty-first century.

Linked to this was an extraordinary reduction in infant mortality rates: infant deaths per 1,000 live births dropped from 182 in the early 1950s to below 60 by the beginning of the 1970s and around 20 at the beginning of the new millennium, all of which was linked to improved sanitation and water supplies and much better medical treatment, including the widespread use of antibiotics (indeed, this is a positive example of the technology replication I discussed at the end of Chapter 1).

Even though the fertility rate has dropped rapidly since the 1970s – partly a reflection of China’s one-child policy and the much wider use of contraception across the region as a whole – the decline has not been fast enough to prevent a population explosion.

In the early 1950s, East Asia had a population of fewer than 700 million.

Half a century later, the population had more than doubled.

These numbers, although impressive, say little about the

economic

consequences of demographic change.

Ever since Thomas Malthus

first wrote his

Essay on the Principle of Population

, there has been a heated debate over whether changes in population size are bad for welfare (the Malthusian subsistence argument), good for welfare (what might be termed the human ingenuity argument) or entirely neutral for welfare (the income per capita rather than total income argument).

Yet each of these positions misses the main economic point.

Demographic change is significant because age structures change.

In any one country, it’s possible to experience both a demographic dividend and a demographic deficit.

The dividend occurs when the population of working age is large in relation to the population of non-working age.

Those of non-working age include children, teenagers and the elderly.

The arithmetic is straightforward.

If there are lots of ‘producers’ but not many ‘dependants’, the burden on the producers is relatively light.

If, on the other hand, there are not many producers but plenty of dependants, the burden on the producers is rather heavy.

Population explosions can, therefore, be good news for an economy because, at some point, the proportion of those in work will rise in relation to those doing other things.

In these circumstances, it’s relatively easy for those in work to support those at either end of the age spectrum.

Such was the case in the UK in the nineteenth century and in East Asia over the last fifty years.

High rates of economic growth per capita were partly led by productivity, but also supported by the demographic dividend.

The demographic dividend is like a surfer’s wave.

The wave lifts the surfer high up, it provides a moment of excitement in the surfer’s life but, eventually, it fades away.

Demographic dividends don’t occur quite so frequently as the surfer’s wave but they have a similar effect: they temporarily raise the growth rate of an economy.

Unlike surfers’ waves, though, they can persist for many decades.

If handled well, they can help create a virtuous economic circle.

Improved healthcare for infants increases their chances of survival and, as a

result, women choose to have fewer babies.

Families can invest in their children’s education, knowing the investment is worthwhile.

As women become better educated, and are more knowledgeable about contraception, they can spend more time working and less time having children.

The opportunity cost of childbirth rises, thereby placing downward pressure on the fertility rate.

The size of the workforce increases because of both the increased number of infants surviving to adulthood and the higher participation of women in the workforce.

With an expanded workforce, the volume of savings increases, allowing funds to be channelled to investment projects, which lift incomes even further.

And, with a more educated workforce, human ingenuity can lift productivity, allowing more outputs for given inputs of raw materials.

Like a surfer, it’s not always easy to jump onto these demographic waves.

Sub-Saharan Africa has by far the greatest struggles.

Improved medical provision has significantly reduced the rate of infant mortality, but prospects in adulthood remain poor – too many wars, too many diseases for those of working age (most obviously AIDS and malaria) and too little protection of property rights.

What is the point of investing in education if the educated die early?

For many years, Latin American nations also struggled.

Some attribute their misfortunes to the prevalence of military

juntas

and dictators and, thus, the absence of democracy; but there is no shortage of non-democratic regimes in Asia, many of which have delivered rapidly rising living standards.

A more likely explanation, in my view, is that Latin American economies had major problems with property rights, inflation and openness, thereby reducing incentives both to save and to trade.

4

For the developed world, the problem is not so much the inability to jump onto a demographic wave but, instead, working out what to do when it’s time to jump off.

No longer are these nations benefiting from a demographic dividend.

Instead, their leaders should be worrying about a demographic deficit.

The quandary is best expressed through the use of ‘dependency ratios’, defined as the ratio of the sum of the population aged between zero and fourteen (below working age) and that aged sixty-five and above (retirees) to the population aged between fifteen and sixty-four.

While the demographic dividend is at work, the dependency ratio declines.

As the wave crests, the ratio begins to rise, signalling the threat of a demographic deficit.

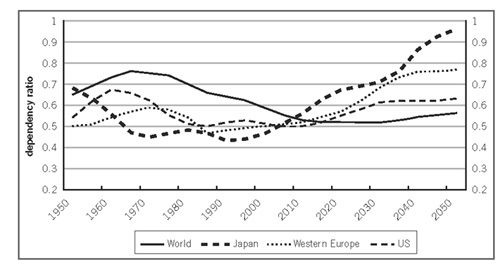

Figure

8.1

shows movements in dependency ratios for nations and regions within the developed world compared with the global average.

From the 1970s through to the early 1990s, the developed world was riding the demographic wave.

Dependency ratios fell rapidly.

The baby boomers, ensconced in nurseries and schools in the 1950s and 1960s, entered the workforce, swelling the numbers employed.

Those same boomers are now approaching the end of their working lives with the result that dependency ratios are now rising.

Meanwhile, fertility rates in some countries – notably Japan, Germany and Italy – are now so low that populations are in the process of shrinking.

By the middle of the twenty-first century, according to the United Nations’ ‘medium variant’ calculations, Italy’s population will have declined by 3 million, Germany’s by 10 million and Japan’s by 26 million.

Given that the population of the world as a whole is expected to rise by 3 billion over the same period, this is a remarkable shift in demographic fortunes.

Figure 8.1:

The Western world is approaching old age…

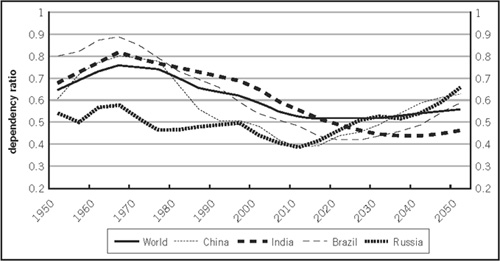

Figure 8.2

… but the emerging world is only in middle age

Source: United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision

Admittedly, populations in the emerging world are also, on average, getting older.

Figure

8.2

shows dependency ratios for some of the largest emerging economies in the world.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when life expectancy was low and fertility rates high, dependency ratios were elevated because there were lots of children and not so many workers.

That pattern changed in the 1970s and 1980s when dependency ratios began to decline: youths, in plentiful supply, entered the workforce and contraception became increasingly prevalent, lowering fertility rates.

Populations in the emerging world will eventually age.

The United Nations currently estimates that dependency ratios will rise first in Russia and China, from around 2020, with others following suit over the following thirty years.

These increases present major challenges – China, famously, will be the first

country to grow old before it grows rich – but they do not alter the underlying fact that the ageing process in the developed world is much more advanced – in fact, thirty years earlier – than in most other countries.

5