LOSING CONTROL (16 page)

Authors: Stephen D. King

This scenario is no more than a description of likely events based on simple microeconomic theory.

It fits, however, with the historical record.

Ultimately, globalization has always been associated with a tension between winners and losers, whether the process of globalization has been market-led or otherwise.

The Roman Empire had plenty of winners, but the vast number of slaves brought in to build cities and power ships would not count themselves among that happy throng.

The Silk Road, sustained by China’s Tang dynasty and then by the Mongols under Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan, proved to be a most effective trading route for silk, spices, Arabic horses and religion (Buddhism found its way from India to China along the Silk Road).

It was also a murderous road, with the ruling Mongols

and a growing numbers of opportunistic bandits happy to indulge in death and destruction in pursuit of material gains (if the Mongols didn’t kill you off, the bubonic plague served the same purpose).

And, as we saw in Chapter 2, globalization under the British Empire was hardly good news for all concerned.

It was no great surprise, then, that the end of the nineteenth century marked a huge increase in nationalism.

The Industrial Revolution delivered huge amounts of economic progress, but only a fool would argue that everyone benefited.

Nationalism, in part, was a protest against an empire that had unfairly kept the benefits of economic progress residing with a privileged minority.

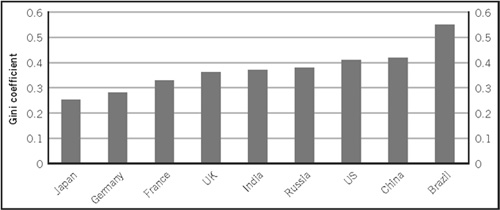

According to the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, the US and China have roughly equivalent income distributions, as measured by Gini coefficients.

(The Gini coefficient is typically expressed as a ratio between 0 and 1, where 0 represents a precisely

equal income distribution and a figure of 1 implies that one person has made off with all the income.

It’s no great surprise that countries ruled by despots tend to have very high Gini coefficients.) By Western European or Japanese standards, both the US and China are very unequal societies.

This is an intriguing result given that the US is regarded as the arch-capitalist economy whereas China still, publicly, hangs on to its communist credentials.

Figure 6.1:

Gini coefficients

Source: World Development Indicators 2009, World Bank

There are three key problems with this data, at least for the purposes of my argument.

First, there may be no statistical consistency across countries, leading to an apples and pears problem.

Second, the source years for the data vary enormously, from 1993 in Japan to 2007 in Brazil.

Third, because the World Bank offers no consistent time series, it’s difficult to work out how globalization may have affected income inequality over time.

Nevertheless, other sources are very much consistent with the idea that both the US and China have seen big increases in income inequality in recent decades.

The US Census Bureau calculates that, between 1967 and 2007, the Gini coefficient for American household income rose from 0.397 to 0.463.

The share of household income delivered to the highest quintile rose over the same period from around 43 per cent to 50 per cent.

Meanwhile, the ratio between the richest 5 per cent of households and the poorest 10 per cent jumped from 11.7 to 14.6.

Chinese data are far more difficult to obtain and offer nothing like the wealth of information provided by the US statisticians.

However, a paper by Ximing Wu and Jeffrey M.

Perloff published in 2004 provided the first consistent set of estimates of China’s Gini coefficient.

4

Their numbers suggest the coefficient rose from 0.31 in 1985 to 0.415 in 2001 (the corresponding figures for the US were 0.419 and 0.466).

While the evidence is consistent with my globalization narrative, consistency alone proves nothing.

In the US, there are plenty of competing – and complementary – explanations for widening income

inequality.

One obvious explanation for the limited progress of those at the bottom of the income distribution is that many of those in that segment may be immigrants: while they may be low paid by American standards, they might still be doing well compared with those who ‘stayed at home’.

Moreover, as with my Romanian cab driver’s offspring, second-generation immigrants might be able to leap up the income ladder.

That, after all, is part of the American dream.

The problem with this explanation, however, is not just that some household segments in the US have remained very poor but, also, that a huge proportion of the benefits of economic growth have gone to segments that already were very rich.

The big story in the US in recent decades has been the failure of the vast majority of people to benefit from sustained economic growth.

Overall income levels may have risen, but very few have become significantly better off.

The very rich have become fabulously rich.

This looks like a rent-seeking story.

Is there a connection with China or, indeed, the emerging economies more generally?

There are plenty of nationally based explanations for the widening income gap.

One of the more popular is the impact of education on income distribution over time.

The idea is that, just like any other investment, investment in education will produce higher returns.

Thus those who receive better or more education will tend, over a number of years, to earn more income than those who chose to leave school or college earlier.

Given that the numbers in tertiary education in the US increased dramatically in the decades following the Second Wold War, this human capital theory points directly to a rise in income inequality.

5

To take a simple example, imagine identical twins, one of whom goes to college while the other decides to head into the big wide

world.

Clearly, the former takes a pay cut in the short term, both through salary foregone and payment of college fees.

For the sake of simplicity, I’ll ignore this loss and assume that, on leaving college, the student commands a starting salary identical to her sister of, say, $10,000.

Now imagine that the salary of the college graduate rises at 5 per cent per year while that of the school leaver rises at 2 per cent per year.

Ten years later, the college graduate is earning well over $16,000 while the school leaver is languishing on a little over $12,000.

Another ten years go by and the college graduate is enjoying an income of over $26,000 while the school leaver is stuck under $15,000.

Ten years further on and, by the time middle age makes its mark, the college graduate is on $43,000 while her sister brings home just $18,000.

If we repeat that experiment at the national level, if the proportion of college graduates in the workforce rises over time, and if their incomes typically grow more quickly because they have the right kinds of skills, it’s more than likely that income inequality will increase.

It is merely a long-term consequence of market forces rewarding those who have the appropriate skills.

On this argument, globalization is largely irrelevant.

While it might be true that college graduates can look forward to higher returns, that’s not the whole story.

A paper by Frank Levy and Peter Temin demonstrates that the vast majority of Americans, whether or not they’ve received a college education, have seen their incomes rise much more slowly than the rate of productivity growth.

6

In other words, although output has been rising, most people in the US have received only very modest benefits.

The authors note, ‘In the quarter century between 1980 and 2005, business sector productivity increased by 71 per cent.

Over the same quarter century, median

weekly earnings of full-time workers rose from $613 to $705, a gain of only 14 per cent (figures in 2000 dollars).’

They also attempt to gauge the extent to which the ‘skills’ of graduates in relation to high-school leavers may have led to growing income inequality.

In their words, ‘For all groups of men – both BA’s and high school graduates – the median worker’s compensation grows roughly in line with productivity until some date between 1970 and 1980.

After that date (which varies by group) the median worker’s compensation lags increasingly behind productivity growth.’

The truth is that, while the US economy has shown impressive growth in recent decades, certainly when compared with some of its main industrial rivals like Germany and Japan, most Americans – educated or not – have experienced only modest benefits.

This is a totally different experience from the 1950s and 1960s, when the benefits of productivity growth were spread much more evenly.

Levy and Temin argue that the primary reason behind the shift in income distribution is the demise of institutions created during the Great Depression that were designed to spread the benefits of prosperity more widely.

These included unions, centralized bargaining frameworks for businesses, workers and government and a protected minimum wage, all of which were dismantled as the economic failures of the 1970s gave way to the laissez-faire Washington Consensus of the 1980s and beyond.

Perhaps not surprisingly, others have disputed these claims.

For example, Stephen N.

Kaplan and Joshua Rauh suggest that institutional arrangements played only a minor role in the huge income gains for those in the top echelons of the earnings spectrum.

7

They also dismiss so-called trade-based theories, which argue that higher incomes accrue to those who can exploit comparative advantage while lower incomes come to those in the wrong industries at the wrong time (‘it seems difficult for trade [theories] to explain the increase in the top end of venture capital investors, private equity

investors and, particularly, lawyers and professional athletes’).

For them, the key explanations are (i) so-called superstar theories (there is only one Jack Nicholson and only a handful of truly successful hedge fund superstars); (ii) greater scale, particularly on Wall Street, where the amount of capital traders can play with is much greater than in the past; and (iii) technological advances that allow traders and the like to make more informed bets and allow David Beckham to be admired all over the world.

8

I struggle with these ‘domestic’ conclusions for three reasons.

First, as already noted, the rise in income inequality in the US has been matched by a similar rise in China.

There are good reasons, in my view, to make a connection.

While there are numerous reasons for rising income inequality in China (according to Wu and Perloff, inequality is on the rise within both rural and urban areas), the most obvious reason is the growth of urban populations (where incomes are higher) at the expense of rural populations (where incomes are still mediaeval).

The growth in urban populations, in part, reflects the investment that has poured into the coastal regions of China in recent decades.

As we saw in Chapter 3, some of that investment has been the direct result of the decisions made by multinationals to relocate to China.

Other investment has stemmed from the ability of Chinese firms to make inroads into the Japanese

keiretsu

system since the 1990s.

Additionally, there has been a sizeable increase in the number of Chinese students benefiting from tertiary education.

According to the World Bank, the percentage of Chinese students enrolling into tertiary education rose from a mere 6 per cent of school leavers in 1999 to 22 per cent in 2006.

These numbers are still tiny compared with percentages seen elsewhere: in the US, for example, the

equivalent figure is 82 per cent while, for the UK, it’s 59 per cent.

However, given that China’s population is four times the size of America’s and twenty times the size of the UK’s, the increase that has taken place in just a handful of years is remarkable.

Through investment in both physical and human capital, the rapid urbanization of China appears to have global implications that are poorly captured in the largely domestically driven explanations of growing inequality elsewhere in the world.