Living Low Carb (23 page)

Authors: Jonny Bowden

The second reason ketosis has gotten a bad rap is a reversal of a medical fact. Ketosis is one of the metabolic adaptations to starvation. When you’re starving, the body uses ketones for fuel. Starving is bad. Therefore, people who didn’t think about it very clearly reversed the order and assumed that since ketosis is (or, rather, can be) one of the

reactions

to something bad, ketosis

itself

must be bad. That’s like assuming that umbrellas cause rain. Ketosis in starvation is very, very different from ketosis in the ketogenic (high-fat or high-protein) diet. Why? In starvation, the body is

breaking down muscle

in the absence of dietary protein. In the low-carb diet, dietary protein is plentiful and prevents the loss of muscle that occurs with true starvation. The loss of body protein is actually what causes death from starvation. When you supply sufficient protein in the diet, this simply doesn’t happen.

Are Ketones Dangerous?

Hardly. They’re a perfectly good source of energy. Drs. Donald and Judith Voet, authors of a popular medical biochemistry textbook, say that ketones “serve as important metabolic fuels for many peripheral tissues, particularly heart and skeletal muscle.”

7

And a recent paper coauthored by a number of distinguished researchers, including one from Harvard Medical School, stated that ketones provide an efficient source of energy for the brain and that mild ketosis—the kind you achieve on a low-carb diet—could have a wide range of benefits for conditions ranging from Alzheimer’s to Parkinson’s.

8

A ketogenic diet should not be used by three groups of people: (1) uncontrolled type 1 diabetics (for the reasons outlined above); (2) pregnant or nursing women (not because higher levels of ketones in the blood are dangerous, but just because we don’t know for sure if they have any effect on the baby); and (3) people with existing kidney disease (see myth #5 for a full explanation of the connection between protein and kidneys).

If you are not in one of these three groups—type 1 diabetics, pregnant or nursing women, or people with existing kidney disease—the ketogenic diet is

perfectly and utterly safe

.

Let’s take a look at the science.

A recent study in the

Journal of Nutrition

looked at the effects of a sixweek ketogenic diet on risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

9

The study found

improvements

in triglycerides and insulin levels, plus a slight

increase

in HDL cholesterol (the “good” kind). Most importantly, the

type

of LDL (“bad” cholesterol) tended to change from the kind that’s dangerous (pattern B) to the kind that’s not (pattern A). Other studies have shown similar results.

10

K

ETONES FOR

A

LZHEIMER’S

?

In Alzheimer’s disease, some brain cells have difficulty metabolizing glucose, the primary source of energy for the brain. Deprived of fuel, some of these valuable neurons may die.

Ketones to the Rescue

Ketones are such good fuel for the brain that a Colorado biotech company called Accera is currently developing an oral liquid that helps the body produce more of them.

*

The drug—called Ketasyn—is currently in Phase II trials as a potential adjunct treatment for Alzheimer’s.

Ketones are a wonderful alternative fuel for the brain, which functions quite well on them after a brief period of adaptation. The patients enrolled in the Ketasyn trial showed significant improvement in memory and cognition.

*

http://www.drugresearcher.com/Emerging-targets/Brain-energy-boost-slows-Alzheimers

A recent study at the University of Cincinnati and Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati specifically looked at the effects of a very-lowcarbohydrate diet on cardiovascular risk factors in fifty-three obese but otherwise healthy women. The women were placed on either a very-lowcarbohydrate diet with unrestricted calories, or a low-fat diet that was calorierestricted. The low-carb group lost significantly more weight and, more importantly, more

body fat

than the low-fat group. (Interestingly, after the study, both groups of women wound up maintaining their weight loss on about the same number of calories—1,300.)

This last-mentioned study is particularly interesting for a couple of reasons. One, the low-carb group

was

in ketosis, but as the authors noted, the level of ketones wasn’t even close to that seen in starvation or diabetic ketoacidosis and presented no problems whatsoever. Two, the subjects on the very-low-carbohydrate diet experienced significantly more weight loss than the low-fat group

and

maintained great readings for blood chemistries and cardiovascular risk factors

while consuming more than 50% of their calories as fat and 20% as saturated fat

. Current standards for healthful eating include reducing total fat intake to less than 30% of total calories and decreasing saturated fat to less than 10%, which is supposed to both lower cholesterol and decrease the risk of obesity. These subjects accomplished the same thing while eating a heck of a lot more fat—and saturated fat—than the current standards,

plus

they lost more weight in the bargain. The authors wisely conclude that “this study provides a surprising challenge to prevailing dietary practice.”

11

Finally, ketogenic diets have been used as treatments for childhood epilepsy for more than seventy years. They are currently used at seventyeight centers in the United States alone, including Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, the UCLA School of Medicine, Children’s Hospital in Boston, the Montefiore Medical Center and Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York, and the Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, whose Web site states: “No patient has had serious complications.”

Do You Have to Be in Ketosis to Lose Weight on a Low-Carb Diet?

No. You don’t.

Ketosis is actually only a feature of some low-carb diets, and not even that many. It is stressed in Atkins; it is likely (but not mandatory) in Protein Power; it is a feature of the Lindora program and the GO-Diet. Many other low-carb programs don’t even mention it. The point is that it is not something to fear. Many nutrition experts—myself included—feel that you don’t have to be in ketosis to get the benefits of a low-carb diet. You can “flirt” with ketosis, be on the cusp of ketosis, but unless you are very metabolically resistant, you may be able to get the benefits of low-carb eating without ever worrying about your ketone levels.

Perhaps the most sober and rational summary of the ketogenic diet is given by Lyle McDonald, who wrote the definitive book on the subject and accumulated the greatest number of scientific references on ketosis ever seen in one place. He says: “After years of experimenting with the [ketogenic] diet myself, and getting feedback from hundreds and hundreds of people, about the best anyone can say is that the ketogenic diet is a diet that works very well for many but not for all.”

Amen.

BOTTOM LINE

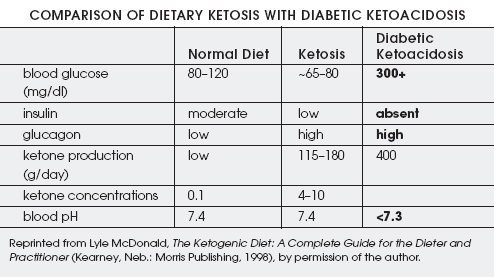

Dietary ketosis is not the same as diabetic ketoacidosis. The ketosis of a low-carb diet is not the same as ketosis in starvation. Many studies have demonstrated the safety of ketogenic diets, even for children

.

MYTH #4: Low-Carbohydrate Diets Cause Calcium Loss, Bone Loss, and/or Osteoporosis

This criticism of low-carb (or high-protein) diets is based on the fact that higher levels of protein result in higher levels of calcium in the urine, leading some people to the erroneous conclusion that protein causes bone loss. But a tremendous number of recent studies are showing something quite the opposite.

Want Strong Bones? Eat More Protein!

The Framingham Osteoporosis Study investigated protein consumption over a 4-year period among 615 elderly men and women with an average age of 75. The amount of protein eaten daily ranged from a low of 14 grams a day to a high of 175 grams. And guess what? The people who consumed

more

protein had

less

bone loss! Those who ate less protein had more bone loss, both at the femoral bone and at the spine. The study also found that “higher intake of animal protein

does not appear to affect the skeleton adversely

.”

12

(Emphasis mine.)

Calcium gets absorbed better on a higher-protein diet, even if there is somewhat more

urinary

calcium excretion. High-protein diets in two recent studies resulted in

significantly more

calcium absorption than the low-protein diets, which were associated with

decreased

absorption.

13

Interestingly, the actual “low-protein” diet that caused decreased calcium absorption in these studies had about the same amount of protein that the government recommends for adults! The authors concluded that this fact “raises new questions about the optimal amount of dietary protein required for normal calcium metabolism and bone health in young women.”

14

And a recent study in

Obesity Research

looked at a high-protein versus low-protein diet to determine whether the protein content of the diet impacted bone mineral density. It did.

Bone mineral loss was greater in the low-protein group

.

15

In other words, without enough protein, you just ain’t gonna build (and preserve) strong bones, and the definition of “enough protein” may turn out to be a lot more than we previously thought.

The Verdict on Protein: Not Guilty

So, how did protein get this bad reputation for causing calcium loss and osteoporosis? It partly stems from something in the body called the acid– base balance. All foods eventually digest and present themselves to the kidneys as either acid or alkaline (base). When there is too much acid, the body needs to buffer it, and calcium is one of the best buffering agents. Meats—along with many other foods, especially grains—are known to be acid-producing; hence the deduction that high-protein diets would cause a leaching of calcium from the bone in order to alkalize the acid content.

But here’s the thing: we now know that if you take in enough alkalinizing nutrients, this doesn’t happen. If you balance your high-protein foods with calcium (and potassium), you will not lose calcium from your bones! An interesting side note: you can take all the supplemental calcium you want; if you don’t get enough protein, it’s not going to make much difference to your bone health. The studies are very clear on this:

extra calcium is not enough to affect the skeleton when protein intake is low

.

16

In short, it doesn’t matter if there is a little more calcium in the urine as long as the body is holding on to more calcium than it’s losing (i.e., is in “positive” calcium balance). And it will do that when there’s plenty of protein plus calcium (and other minerals) in the diet.

BOTTOM LINE

Higher protein intakes do not cause bone loss or osteoporosis, especially in the presence of adequate mineral intakes. In fact, lower protein intakes are associated with more bone loss

.

MYTH #5: High-Protein Diets Cause Damage to the Kidneys

You will often hear from ill-informed sources that a high-protein diet damages the kidneys. Not so. Consider the following: everyone knows about step classes and aerobics. They are great calorie burners, get the blood and oxygen flowing, are good conditioners of the cardiovascular system, and, with certain variations, can even be good for muscle toning. So they’re a good thing, right?

Yes.

Except if you have a broken leg.

If you have a broken leg, or a sprained ankle, or shin splints, I’m going to suggest that you not take a step class until the injury heals. Under these special circumstances, the very weight-bearing that does so much good for the normal person is going to be more stress than you need during the healing phase. I’m going to tell you to stay off the leg, let it heal, and avoid putting additional stress on it at this time.

Does the fact that step class is not good for a person with a broken leg mean that the step class

led

to the broken leg?

No. And ketogenic diets do not—I repeat,

do not

—cause kidney disease. If your doctor says they do, politely ask him or her to show you the studies. (They don’t exist.) Ketogenic diets are, however,

not

a good thing if you have an

existing kidney disease,

much the way a step class is not a good thing if your leg is already broken.