Living Low Carb (22 page)

Authors: Jonny Bowden

The fish was dolphin.

You can, I’m sure, see the problem.

No one wanted to patronize an establishment that was so heartless as to serve up Flipper for the gastronomical whims of its customers.

Quite understandable.

Problem was: “dolphin”

isn’t

“Flipper.”

Dolphins were, and are, quite ordinary but tasty fish that look exactly like fish: they bear not even a passing resemblance to the bottle-nosed dolphins that delight us at Sea World and with whom they happen, by some weird taxonomical screwup, to share the same name. In fact, they aren’t even the same

species

(one being, of course, a fish, while the other is a mammal). Plus, the dolphin (fish) does not perform adorable tricks and does not appear to have much rapport with the average human being. (Some sources, in fact, refer to the dolphin fish as “dolphinfish,” to distinguish it from the mammal.)

But go tell that to the table for four in the back where the kid is crying and the parents are threatening to never come back to this restaurant, ever.

Waiters explained, probably as many times as they had to say, “Hi, I’m Jason and I’ll be your server for today,” that dolphin was not

dolphin

. Yes, they did in fact share the same name, but one was a

fish

and one was the lovable marine

mammal

, and the dish on the menu, sir, was not Flipper.

Didn’t matter.

No matter how many times this conversation was repeated in restaurants throughout the city, and probably throughout the country (though I can personally attest only to the number of times I heard it in New York City), it fell on deaf ears.

So restaurant owners did a smart thing.

They changed the name of the fish.

“Dolphin” now became known as “mahi-mahi,” which is the Hawaiian name for the dolphinfish.

End of problem.

Which brings us to ketosis.

Ketosis: Friend or Foe?

It is very difficult to read about—or write about—low-carbohydrate dieting without dealing with the term

ketosis

. If you’ve been around low-carb diets at all—if you’ve experimented with them, talked about them to your friends, read about them, read

warnings

about them—you’ve surely heard of ketosis. You’ve probably heard that it’s some kind of metabolic state that accompanies these diets and that you should avoid it—and those “high-protein” fad diets that produce it—at all costs. Several years ago, in a column at iVillage. com, I wrote the following, which is still true today:

Ketosis is so misunderstood and maligned that I really feel it’s worthwhile to go into it in some detail. For those of you who are new to this, ketosis is something that happens in the body when you eat very, very few carbohydrates. Since there’s very little sugar coming in, your body burns fat for fuel almost exclusively—this is called “being in ketosis.” Many popular diet programs have made use of this “metabolic advantage,” most famously the Atkins program, and dietitians (and doctors) have been screaming about how dangerous it is ever since, although they can never seem to tell us why. It’s been popular among dieters because, among other things, even the most metabolically resistant people usually lose weight on a ketogenic diet, and many people, after an initial adjustment from a sugar-burning to a fat-burning metabolism, feel great, with increased energy and a noticeable sense of well-being.

Atkins himself wrote rhapsodically of ketosis in the first and second editions of his

New Diet Revolution

, calling it “one of life’s charmed gifts…. As delightful as sex and sunshine, and it has fewer drawbacks than either of them.” It was Atkins who gave ketosis the nickname “the metabolic advantage.” (For more on the metabolic advantage, see

chapter 5

, page 85)

So how can something so harmless and benevolent (and so conducive to weight loss) be widely considered one of the most dangerous states the body can be in? (If you doubt that this is the prevailing opinion, try asking your mainstream doctor what he or she thinks of it. Or ask a dietitian.)

The reason is quite simple, actually. For the better part of thirty years, mainstream medicine, dietitians, and most of the critics of the low-carb diet have

completely confused two conditions

, as different from each other as the dolphin (fish) and the dolphin (Flipper). One of those conditions is ordinary, benign, dietary ketosis, of which we’re speaking here. The other is a life-threatening condition called

diabetic ketoacidosis

(more on this in a minute). Getting the mainstream to understand the difference has been harder than getting the kid at the table to understand that the restaurant really isn’t serving cooked Flipper.

Atkins, in the last edition of

New Diet Revolution,

pretty much gave up the thirty-year fight to get the medical establishment to understand the difference; he stopped using the term

ketosis.

He switched to the term

lipolysis

(fat breakdown). Only time will tell if the name change is as successful as the switch to mahi-mahi has been.

The Real Deal on Ketosis

So what is this thing called ketosis, and why should we care?

Note: I’m going to go into a little biochemistry here. I’ll try to make it painless, though I understand that, for many, the term

painless biochemistry

is an oxymoron. If you want to skip the next few paragraphs, believe me, I won’t be offended. If, however, you’d like to

skewer

the next person who tells you how dangerous your low-carb diet is because of ketosis, you might want to read the next few hundred words.

Your body has three main sources of fuel: carbohydrates (glucose), proteins (amino acids), and fats (fatty acids). These are broken down and combined in different ways—fats and carbs to produce energy or to be saved as fat; protein to build up tissues, bones, muscles, enzymes, and the like. Remember that the whole purpose of a low-carb diet is to make your metabolism more of a fat-burning machine than a sugar-burning machine. As Lyle McDonald, one of the best-known authorities on the ketogenic diet, says, “Ketosis is the end result of a shift in the insulin/glucagon ratio and indicates

an overall shift from a glucose- (sugar)-based metabolism to a fat-based metabolism

.” (Emphasis mine.) In other words, the whole idea is to get your body to switch fuels from primarily carbs, its preferred immediate source of energy, to primarily fat.

Carbs, or sugar, are the first source of energy used by the body, with fats providing the best

long-term

source of energy. Yet high levels of carbohydrate produce, for many people, higher levels than desirable of the hormone insulin, and fat cannot be “burned” or “released” to any significant degree in the presence of insulin. So for someone with a weight problem, high carb intake will provide all the fuel they need for living (and probably plenty for storage as fat in addition) and will raise insulin levels enough so that fat isn’t released or burned.

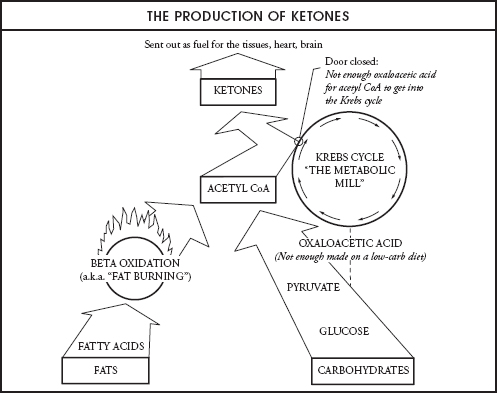

Normally, carbs are broken down into glucose, and then pyruvic acid, and then a substance called acetyl CoA. Fats are broken down into their component parts, fatty acids and glycerol, then

further

broken down (by a process called beta-oxidation) into two carbon fragments which

also

combine to make acetyl CoA (see illustration on page 104).

On a “normal,” high-carb diet, two things happen to the acetyl CoA. First, some of it gets broken down in the liver into ketone bodies. It’s important to remember that this is a

normal

part of metabolism. You are making ketone bodies right now while you sit there reading this book. The liver is

always

producing ketone bodies. As McDonald says, “Ketones should not be considered a toxic substance or a by-product of abnormal human metabolism. Rather, ketones are a normal physiological substance that plays many important roles in the human body.” (This, of course, did not stop Jane Brody of

The New York Times

—one of the biggest apologists for the highcarbohydrate/low-fat diet in America—from calling ketones “toxic compounds that can damage the brain” and “pollute the blood.”)

So the liver makes ketones—which are essentially by-products of fat metabolism (specifically the breakdown of acetyl CoA)—

all the time

.

What’s the

other

thing that happens to the acetyl CoA?

Well, on a diet with plenty of carbohydrates, the acetyl CoA combines with a by-product of

carbohydrate

metabolism called

oxaloacetic acid

. When acetyl CoA combines with oxaloacetic acid, it enters an energy-production cycle called the Krebs cycle. (This is what is meant by the old saying “Fat burns in a flame of carbohydrate.” Without the carbohydrate necessary to produce the oxaloacetic acid, the acetyl CoA cannot gain admission to this energy cycle and be burned.)

So those are the two pathways that acetyl CoA (which, you remember, is produced by

both

fat breakdown and carbohydrate breakdown) can take when there’s carbohydrate in the system.

But what happens when there isn’t?

What happens when you go on a very restricted carbohydrate diet and there is not enough carbohydrate (glucose) coming down the pike to produce the oxaloacetic acid necessary to take the acetyl CoA into the Krebs cycle? Well, the acetyl CoA

accumulates

in the liver. And the liver promptly breaks it down into ketones (also known as ketone bodies—if you really want to get technical, there are three of these ketone bodies, and their names are acetoacetate, beta-hydroxybutrate, and acetone; it’s the release of the acetone that gives you that “fruity” breath). The major determinant of whether the liver will produce a significant or negligible amount of ketone bodies is the amount of sugar (liver glycogen) that’s around. In a low-carb diet, there’s not a lot. So all of the acetyl CoA has to be broken down into ketones, and these ketones—products of

fat

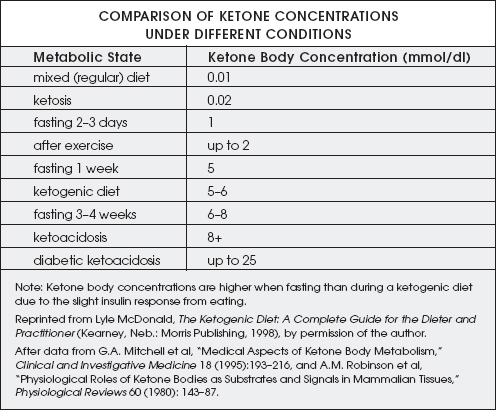

breakdown—are now being made in sufficient quantities that you can detect them in the urine. The “normal” level of ketones in the blood is about 0.1 mmol/dl; mild ketosis is 0.2 mmol/dl. Ketogenic diets typically produce between 5 and 7 mmol/dl (see chart above).

Please remember: these ketones are benign products of normal metabolism, and the fact that you can actually see their presence in the urine (by the use of ketone test strips) simply means that your body is breaking down fat for energy in measurable, significant amounts.

So, how did ketone bodies get such a bad rap?

There are two reasons.

Ketosis and Diabetic Ketoacidosis

To understand the primary reason ketones have been vilified, we have to look at the type 1 diabetic. As you may remember from earlier discussion, insulin is responsible for getting sugar

out of the bloodstream

and

into the cells

, thus keeping blood sugar (glucose) within a tightly controlled range. Insulin also keeps fat from being broken down, which is why it needs to be in balance with its sister hormone, glucagon. Glucagon is responsible for releasing fat into the bloodstream, where it can be broken down and used for energy. Insulin is responsible for

storing

it.

The type 1 diabetic cannot make insulin.

With no insulin, two things happen, neither of them good. One, blood sugar rises to very dangerous levels. Two, with no insulin to put the brakes on glucagon, fat is broken down and released into the bloodstream faster than it can possibly be used, and the production of ketone bodies is seriously ramped up. In addition, these ketones

cannot

be used by the body tissues like they can in normal dietary ketosis. This is because there’s tons of glucose around, which is the preferred fuel, so the ketones just keep accumulating at an alarming rate. This state is called

diabetic ketoacidosis

, and it is indeed very dangerous and life-threatening to an untreated type 1 diabetic. Remember, a ketogenic diet produces, on average, 5 to 7 mmol/dl of ketones, and does it in the presence of

normal to low

blood sugar. The untreated type 1 diabetic will produce ketones in the range of 25 mmol/dl (350 to 600 percent higher than normal!) and will do it in the presence of

extraordinarily high and dangerous

levels of blood sugar. There is absolutely no comparison between the two states. The person

without

uncontrolled type 1 diabetes has a number of normal feedback mechanisms that will always keep the ketones in a safe range, mechanisms that

do not exist

with the untreated type 1 diabetic. Diabetic ketoacidosis

cannot happen

when there is even a small amount of insulin around, as there

always

is in those not suffering from type 1 diabetes, even when the person is on a ketogenic diet.