Live Long, Die Short (10 page)

Read Live Long, Die Short Online

Authors: Roger Landry

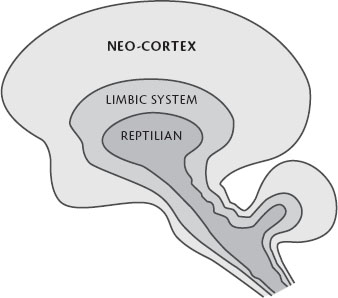

Fear of change is firmly rooted in our brain and isn’t likely to disappear in the near future. We have a three-part brain. The most basic part we share with lower life forms and is called our “reptilian brain.” The most sophisticated part distinguishes us from all other species and is called the “cerebral cortex” or “neocortex.” It is here that all very high-order functions exist, and it’s because of this that you are reading this at all. The middle brain, called

the “midbrain” (or “paleomammalian brain”), we share with other mammals. This is control central for temperature regulation, emotion, and the famous fight-or-flight mechanism. So, when our ancestors came up over a hill and confronted a lion, this area of the brain, specifically the amygdala, jumped into action and released neurotransmitters that revved up our bodies to either

fight

the lion (a questionable decision) or run like hell—take to

flight

from the beast. The amygdala is fear central. When it fires, everything we need to fight or run is activated—and activated big-time. All body functions that aren’t needed to deal with the situation are slowed down, ignored, or inactivated. It is efficient. It is effective. It is perfect.

Compared to today, not too much happened in our ancestors’ world, and when it did, there was a good chance that survival itself was at stake. So when change came, it grabbed our ancestors’ attention. In fact, it more often than not caused them to fear the change. So the amygdala was called into action and, as programmed, revved up all the fight-or-flight systems and shut down other bodily functions, like digestion, urination, and thinking. After all, confronting a lion was not a good time to rid ourselves of waste, or think about how you’re going to get away. It was all automatic. Threat (change) caused fear, and fear caused everything to shut down except

what was needed to fight or run. It’s that simple, and this response remains with us today. So what about the part we

can

do something about?

Change, Dr. Maurer tells us, especially the big bites of change we all characteristically take on, triggers this same instinctual fear. We are wired that way. It may be masked as anxiety, uncertainty, or a zealot-like attempt to change, but it is, in the end, fear. So if we hit our brains with a New Year’s resolution to lose twenty-five pounds, or to be nicer to our spouse, or to learn Italian, we are causing our amygdala to act as if a lion were in our house. Just when we need purposeful thinking, creativity, a rational reason why we should change, and a plan for targeted, purposeful action, our brains essentially shut down because of fear. It is fear that causes us to fail, not succeed. Fear that grabs us precisely when we need a clear mind to develop a plan to change, when we need a reason to change, and when we need higher purpose to suppress our more basic instincts. This fear makes us fearful idiots precisely when we need all of our higher faculties to chart a course to constructive change.

Dr. Maurer is a clinical psychologist, and his answer to this dilemma is to change how we approach change, taking on smaller bites instead of our usual big bites. He advocates

kaizen

, the Japanese technique for making change, whether in our personal lives or in business. Kaizen is about small changes, easily achievable goals that are so small they do not trigger the amygdala to go into alert mode. Goals that might seem ridiculous by our current standards can slip by the amygdala—i.e., not generate fear, or modern-day stress—and therefore leave our needed faculties intact to bring the change to reality.

Katie Sloan is the chief operating officer, senior vice president, and executive director of the International Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (IAHSA) and a colleague of mine. In a speech she gave at Masterpiece Living’s annual meeting, called “The Lyceum,” in 2011, she gave me the clearest picture of the value of this small-step approach to change. She said that if we are walking and make no change whatsoever, we will end up at destination A. If we change our direction only slightly, by just two or three degrees, in time we will end up at destination B,

a long way from destination A!

With just small changes, persistence, and patience, we can make huge changes in our lives.

The way we approach change in our “take no prisoners” society, however, is not as Katie describes it. We do it by innovation, described by Maurer as “a drastic process of change,” which ideally “occurs in a very short period of time, yielding a dramatic turnaround.” Sound familiar? Sound like every New Year’s resolution you ever made? Sound like the typical American approach to weight loss? Don’t think I’m against innovation. Who could be? However, when it is the standard for behavior change, it is usually too ambitious, and at high risk of failure. Why? You got it: It generates fear, maybe of failure, or loss of the familiar, whatever, but fear that shuts down the higher-level cortical functions we need to succeed. As Dr. Maurer tells us, “Change is frightening.… This fear of change is rooted in the brain’s physiology, and when fear takes hold, it can prevent creativity, change, and success.”

John Wooden, one of most successful coaches in college basketball, knew how to make positive change happen. “Don’t look for the big, quick improvement. Seek the small improvement one day at a time. That’s the only way it happens—and when it happens, it lasts.”

4

That’s kaizen.

Kaizen is about small steps. It’s about

asking ourselves small questions

: “What is the simplest thing I can do to begin moving?” “What can I do in five minutes each day to become more positive?” Small questions allow us to begin thinking about a plan for change without triggering the amygdala and setting up roadblocks to success.

Kaizen is about

mind sculpture

, a technique described by Ian Robertson in his book by the same title.

5

With mind sculpture, we imagine ourselves performing the activity that we want to do, and use our senses to do the imagining: feeling the muscles move, smelling the associated smells, hearing the sounds, seeing ourselves performing the act, not as a viewer would view us, but what we would see as we actually performed it.

Maurer tells us that “within minutes of ‘practicing’ a task mentally, using all your senses, the brain’s chemistry begins to change. It rewires its cells and the connections between the cells to create complex motor or verbal skills.” Brain-imaging capabilities have allowed us to “see” this brain activity going on as if the action were really happening. We “fool” our brains into making connections without the fear normally associated with new tasks or behaviors. We rewire our brains so that the desired behavior happens easily, without the amygdala sounding the alarm, without stress or fear impeding our progress toward a new, more positive behavior. Even just a few seconds or minutes each day can build these

new brain connections and allow us to actually perform the new behavior without the usual roadblocks.

Kaizen is about

taking small steps

. Having asked ourselves small questions, decided what small action we might do to change our lives, and used mind sculpture to practice that action and begin to make brain connections that will make it easy to perform, we now take small steps toward our goal. We’re talking

ridiculously

small steps by current standards. Like learning one word of a new language a day, or walking ten more steps each day, or thinking one nice thing about someone. These small steps will not trigger the brain’s survival/fear/change response. The amygdala will remain quiet. We will feel positive about what we’ve done, but more importantly, about our ability to change. And we’ll be on our way toward whatever we want to accomplish.

Kaizen is about

solving small problems

. True, if our doctor tells us we must lose fifty pounds, that’s not a small problem. But asking ourselves small questions, seeing ourselves find the answer to those questions, and taking small steps, like beginning to stand during TV commercials, or spitting out the first bite of a candy bar—those are small changes, baby steps on a journey that will become easier as we accomplish small tasks without fear, without failure. And even when we do “fail,” we have only to take a small step backward to get on track. And as we collect more and more successes, no matter how small, we make huge gains in confidence, and, by adding small increments of change, ultimately eat the elephant, one small bite at a time.

Of course we can. We must, if we are to navigate through a lifetime where the rate of change is ever rising, where whether we prosper, stay healthy, or age successfully is all dependent on our ability to make corrections to, refine, and otherwise modify our behavior. We must.

Dr. Maurer tells us, “Instead of aggressively forcing yourself into a boot-camp mentality about change, give your mind permission to make the leaps on its own schedule, in its own time.”

6

So out with the “just do it” New Year’s resolution, the never-again, seesaw, guilt-ridden approach to bettering ourselves. As some ask, “How’s that working for you?” If it has, terrific; however, you are in the minority. As for

us mere mortals, a more modest approach will serve us well. So, when you’re considering making some changes in your life, consider the kaizen way:

- Identify specifically

why

you want to change. - Then zero in on

what

you want to change. - Ask yourself, “What’s the smallest thing I can do to begin this change?”

- Make that small thing—and

not

the ultimate change—your goal. - Imagine yourself doing that thing.

- When you achieve the small goal, add the next smallest thing you can do.

- If you fail to achieve a goal, just step back to the last achieved goal and add a smaller, more achievable goal to that.

- Keep adding very small increments to your progress. It doesn’t matter how long it takes. You are changing, and moving toward your ultimate goal.

And remember, the journey is as important as the destination.

If we want to grow, we must change. If we are to going to change, we must make changes.

I

t’s the moment of, and for, truth. We’ve talked about our ancestors and how the way they lived over eons determined what we as their descendants need to be healthy and to age well. We’ve learned that their lifestyle is, in fact, a guide to our most basic needs, our authentic human needs as humans. We’ve noted that how we live today is radically different from how our ancestors lived, and that therefore we are a species with Stone Age needs in a microchip world, and we’ve seen how we are paying the price. Recent research has revealed what it takes to be truly healthy and age well, and those revelations look remarkably like those authentic human needs laid down by our ancestors. We know we can’t go back in time, but we can—by knowing what it takes to become authentically healthy and to age successfully—begin to bring these things back into our lives.

So now is your moment. Your moment to honestly assess your current lifestyle. Your moment to find out how far you may have wandered from your basic human needs for health. Your moment to find out just where you are at risk for disease or accelerated decline. This can be scary, I know—I’ve done it myself. But not to worry. These are easy questions to answer. The

hard part is answering them truthfully. Your answers will help guide you to the best recommendations for aging in a better way, a more enjoyable way, a more successful way. There are no right answers, only

your

answers. When you have completed the Personal Lifestyle Inventory, consult the feedback section immediately following. This feedback will help you interpret your score and answers and, most importantly, provide you guidance on which of the Ten Tips in

part II

of this book are particularly important to you.

The Ten Tips offer practical, easy-to-do things you can use to get back on track: things you can do to begin to navigate your way through all the health and aging advice that’s out there, telling you to do this and that, some impossible, some contradictory, some just plain crazy. The Ten Tips are the result of my decades of experience in taking personal histories to uncover disease and its causes as well as to determine the best plan of action. In Masterpiece Living communities, we use similar questions in order to determine an individual’s risk to their health and independence. I’m sure you, too, will find them to be “just what the doctor ordered.”