Little Mountain (4 page)

Authors: Elias Khoury

We feared for the mountain and for its plants. It edged to the brink of Beirut, sinking into it. And the prickly-pear bushes that scratched our legs were dying and the palm tree leaning and the mountain edging toward the brink.

They call it Little Mountain. We knew it wasn’t a mountain and we called it Little Mountain.

When I was three, the parish priest came in his long black cassock and handsome beard. He sat in our house and we all gathered around him in a circle. He started telling us anecdotes and stories. Then, he told us about the achievements of Stalin and the Bolsheviks. He turned to me, ruffled my hair, and told my mother that it was time I was dedicated to Saint Anthony and was given his habit to wear (wearing St. Anthonys habit is a tradition among most of the Eastern Christians in our country; it is worn by children in blessed remembrance of the first Christian monk to have left the city and gone to Sinai to start up the church’s first monastic order).

The habit is brown with a white cord dangling from the waist. I walk down the street imitating the gestures of saints. I walk and around me are children who wear or don’t wear the habit. We proceed in a long line to where the golden icons lie and the glass is tinted by the sun. And when I forget that I have become a saint, I run wild, playing in the gravel and the sand. I fall down in the streets. Then, when I go home, my mother looks over the saint’s soiled habit and slaps and scolds me. Then orders me to kneel down and pray. I kneel down and pray so that the saints might forget that I abandoned them and went off to play with the other children.

I walk, proud in my beautiful brown habit, imitating the priest’s gestures. I go to school, vaunting my clothes and put a round halo of leaves on my head.

The parish priest died all of a sudden. I didn’t understand what it meant. I remember crying because my sister wept. Then, about six months later as I recall (maybe I no longer actually remember the event but have it imprinted in my memory because of the dozens of times my mother told me the story), I went to church with my mother and father. It was the custom to take off the monk’s beautiful garment in church, where it was placed at the altar and candles were lit in offering.

We went to church. I was feeling joyful and rapturous. We reached the heavy door that was always open. It was shut. My father knocked on the door, no one opened. My mother knocked, no one opened. My father said what shall we do. I knocked on the door, kicked it. Leave the habit at the door, answered my mother.

—And the candles?

—We’ll light them next week.

I knocked on the door, kicked it. No one opened. My father helped me out of the habit. I began to cry. My mother took the habit, placed it at the door and made the sign of the cross. I was in tears. My father held me by the hand and we walked home. No one opened the church door. We left the habit at the door, and I went home miserable. No candles were lit the following week.

They came.

Five men, jumping out of a military-like jeep, carrying automatic rifles. Five men wearing big black hats with big black crosses dangling from their necks. They surround the house. They ring the church bells and bang on the door.

Five long black crosses dangling before my mother as she opens the door. She mutters unintelligible phrases. She slams the door shut in their faces and cries.

Five men break down the door and ask for me. I wasn’t there. They find a book with a picture of Abdel-Nasser on the back cover. I wasn’t there. My mother was there, trembling with distress, resentment, and fear. My mother was there. She sat on a chair in the entrance, guarding her house as they, inside, looked for the Palestinians and Abdel-Nasser and international communism. She sat on a chair in the entrance, guarding her house as they, inside, tore up papers and memories.

My mother was there.

I wasn’t there.

I was in the East, searching with short, almost barefoot men in rubber shoes that didn’t keep the cold out. I was in the East, looking for Little Mountain stretched across the frames of men, the sea surging out of their beautiful eyes.

*

The popular name for the Ashrafiyyeh area of Beirut.

**

That is, a feast day, festival, or holiday of religious origin or significance.

†

Burghul

is the crushed wheat used in two major national dishes in Lebanon; it is known in the West as bulgar.

’Araq,

the national drink, is a distilled grape alcohol, aromatized with anis.

*

The president of Egypt from 1954 to 1970 and the most revered leader of Arab Nationalism.

**

That is, the Beirut River and Olive Grove roads, respectively.

*

In the Eastern church, Palm Sunday is an important festival especially for children.

*

As-Sagheer means the little one in Arabic.

*

The area known as Qarantina was the site of a military quarantine hospital under the French Mandate. Later, it became Beirut’s principal garbage dump and part of the urban slum area that constituted the city’s “belt of misery.’’ (See note on p. 28.)

*

The Cairo-based pan-Arab radio listened to extensively throughout the Arab world in the headier days of Arab Nationalism.

**

A region of Syria which is part of the larger

Jabal Druze,

i.e., Druze Mountain, area that led a famous revolt in the mid-1920s against the French Mandate. See Chapter 2.

*

There was famine in Lebanon during World War I owing to the requisitioning of grain for the soldiers by the Ottoman authorities and to hoarding by grain merchants.

*

A corruption of the French “un-deux,” obviously meant ironically by the author.

The

CHURCH

SCENE ONE

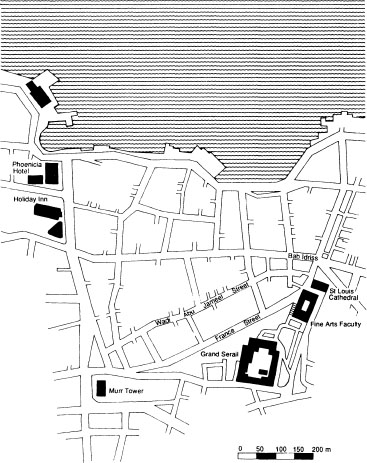

Nine p.m. Drizzle and the sound of gunfire getting closer with every step. We run cautiously, clutching rifles and dreams. We leap across a very long street, called France Street, to take up a new position at the end of it: the church. The voice of the unit commander is resolute and clipped. Go in carefully. Don’t shoot unless absolutely necessary and only at a visible enemy. According to our reconnaissance information, they’ve abandoned the church and set up their fortified positions on Hwoyek Street. We race down the middle of France Street. We can see the church ahead but we can’t see anything in the dense darkness, broken only by flashes of the Doushka

*

up there close to the sky where the Murr Tower silences the Holiday Inn keeping Wadi Abu Jameel

**

out of range of the isolationists’

*

gun-fire. If they want a battle, they’ll have to fight in the streets, for the tall safe building is no longer of any use. We rule the streets, Sameer says. I run, the thin rain trickling between my hand and the rifle butt. The church —I see it, don’t see it. Our dreams are right there in the street, and the shells fly and crash into the small, low buildings. ’Atef greets us. Fighting comrades from the various organizations and parties deploy themselves in the buildings and amid the fallen stone. And the sounds of the battle grow louder.

BAB IDRISS QUARTER

The unit commander is up in front, leading us toward the east. The church is in the east.

We come up from behind. Through the torn-down electricity cables, puddles of water, and mounds of sand. Going through the fine-arts school, we can see the fire the

fedayeen

have lit in front of their bedding, on the platform that was once a stage. We come up from behind and race down a broad street, bullets exploding in the air and on the pavement.

— Deploy.

We deploy.

The first group jumps through the window. Five minutes of silence when every breath is held and fingers stiffen around triggers. The second group jumps. Darkness. We scatter. Then everyone moves forward. The unit commander assigns the groups to their places. We block off all approaches. Darkness, gunfire, not a soul.

Guard-duty is assigned, hide-outs secured.

Butros is walking around looking for the church.

— Butros, were

in

the church.

— But I don’t see anything. Butros takes a taper and lights it in a corner of the church. A pale light quivers. Salem stands up, with his short hair and tall stature; he’s like the carpet-seller I saw as a child carrying the streets on his shoulders. Salem carries the B-7 rocket launcher on his shoulder, and laughs that soft laugh which rings out between the walls. What’s this? This isn’t a church.

Christ is on the floor. The statue of Christ lies twisted on the ground, his right cheek to the floor, his left hand open toward the sky, searching for his broken right hand. The picture of the Virgin practically smashed. Water everywhere. The rain coming in through the windows. Christ stretches his left hand out near the window to catch the rain but it trickles between his fingers and nothing remains in his hand save a wetness that recalls the rain.

—What’s this? cries Salem. This is a smashed up church.

— Quiet!

Sameer improvising on the Grinov

*

and shells of all kinds raining down on us. The first battle in the church. We plunge ahead like arrows, in a blast of noise, then everything is quiet. Our groups slip through, striking deep. Sameer on the Grinov and Jaber firing like someone embracing the rain. The sacrament is complete. We’ve got to know the church —every stone, every recess, every smashed figure —as we pounce, advance, and conquer. We’ve silenced them. The church is a support position, the commander says. Tomorrow, we’ll go on to new positions and take the Bab Idriss intersection. We’ve no losses — except for Ahmed’s slight wound. Rest now and be careful.

Butros in the corner lights his taper and hums faint tunes to himself. I move up and sit beside him. A pale light flutters with the movement of the wind and shapes stretch across the long empty space, empty but for the broken benches, strewn vessels, and twisted statues. Butros gets up and begins to look around. He takes Christ’s hand, stands him upright. Christ stands up with his one outstretched hand. Butros sets off, I fall into step. He picks up a priests brown robe lying in a dark corner. Look. He shouts. We look. Things tremble against the wall and spaces lengthen. He stands at the altar, in his right hand the B-7 rocket launcher transformed into a priests staff. Softly intoning a Latin chant,

*

his voice rises gradually. All eyes turn to the priest standing in his brown robe with his staff and his beard tracing endless circles to the chant. The voice soars. The melody pierces the walls, the words as pebbles under our feet. Eyes widen and the priest grows tall against the wall, advances gradually, swaying. Between phrases, a few shells and red and green shots.

**

— Hey Butros, what’s this?

Childhood springs forth: the church at Deir al-Harf, before its walls were clad in Romanian colors and Byzantine icons, when it was naked like the

fedayeen.

Father Morkos, hands crucified, voice subdued, rising toward the entrance of the sanctuary where stands a boy, rapt with joy. Latin supplications, Byzantine chants, the priest in our eyes. The window is lit up in the colors of the tracer bullets. Butros carries on.

— Don’t you hear? says Salem. -What?

— I hear footsteps, up there. Be careful.

Butros carries on, three of them cluster together. Altar attendants, in their jackets, standing there riveted, marveling at the game.

— Don’t you hear?

The sound of footsteps grows louder. Butros falls silent. Then, suddenly, he wrenches off his priestly robe, clutches his weapon tight. We scatter. The unit commander jumps to his feet, advances. He goes up the stairs, with three comrades behind him. Caution. A battle inside the church? It would have to be an unusual battle.

The four of them return. Nothing. The church’s two priests are still here, and he points upstairs. At first, they thought we were Kataeb,

*

then when they discovered who we were they got very frightened. I reassured them. I asked them not to light a fire and to stay inside the church at least until morning.

Sounds of nearby shelling and of gunfire getting closer. Christ falls to the ground again. Butros stands him up, but he falls once more.

— Impossible, the base is broken.

— But he’ll stand up.

— Even if he stands now, hell fall tomorrow. The battles tomorrow, Butros.

— What’s the difference between war and civil war?

In the interstices between one shot and the next, Salem would find the time to ask such questions. He’d ask the question and not wait for the answer. He’d always say it’s not the answer that’s important. All answers are the same. The thing is to ask the questions. Between questions, muscles would color and faces lift from the sand and rubble, looking for the narrow streets leading to the sea.

The sea’s our goal, the commander says. Once we control the Bab Idriss intersection, we open up the sea road ahead of us. Rabee’, the sailor-turned-fighter, knows the taste of the sea and the sea road. That’s why he flexes like an arrow.

— I’m a master of answers.

Yet Salem goes on asking: What’s the difference between war and civil war?

The narrow streets twist and curve, on either side rock smashed against rock. The sound of the shells crashing against our bodies. To the right, fires, to the left, a low building sagging like an old woman, her joints broken by the shells. Between our line of vision and the sea are buildings and walls and metal. Between the shell and the scream, stone falls against stone.

The narrow street stretches endlessly. Between its beginning and the positions, sounds of footfalls, of groups of fighters shouting and laughing. The narrow street contracts. There is rubble where there should be mounds of sand and sand between the streets and the buildings. Between the hand that fires and the foot that jumps, a body crouches, straightens, crawls. When it arrives, it’ll be holding nothing but the sea.

— What does the war want?

—The war doesn’t want anything. But its saying that the asphalt extends the street to the street opposite. And that on the opposite street there are enough metal studs

*

to make a graveyard.

— Reinforced concrete is resistant. But thick sand stone gives you more of a sense of security. The streets criss cross. But gunfire can open holes in the net, and the fish escape to occupy the sea.

It was four in the morning when we began. The sound of the fighting was growing louder and closer after a two-hour lull. Nabeel was holding his gear tight. The walls beginning to be pierced: first the explosive charge against the wall, then the hands and the hammers coming to widen the breach. Moving from hole to hole, clouded in dust, rubble, and noise. Between each hole, bodies stooped, and we advanced. The fighting was growing louder, drowning our voices and the racket from our breaking through the walls. Walls were the new measure of distance. Our blue jackets were turning white and our hands were covered with the damp dust blowing off the walls. With every wall, we were saving ourselves a street and advanced.

—This is the real Beirut. Talal was saying, covered in dust from head to toe, and laughing with a ring of pride. We’ve learned war and invented new laws.

— We haven’t invented anything yet, said Rabee’. We’ll invent when we get to the sea.

As for Nabeel, he was busy opening up new holes, his body bent over the explosive.

Everyone plugged his ears. The commander was moving back and forth between the passageways of the war and those of the church, making sure of the support groups’ progress. Voices rose and bodies slipped through the dust.

—When will we get there?

Talal was smiling as he told me the story of Monte Cristo. They wrote a novel about him because of one hole he opened in a prison wall. How many novels will be written about us then who’ve opened twenty holes in twenty walls? Down with literature, Nabeel shouted. Careful now. This is the last hole. And then were there and we take them by surprise. Features were hued a bronze-red despite the dust. Everyone looked at his weapon, entrusting it with his last secrets, renewing his pledge of trust in it once again.

Between the last dust and the dust from the shells, the moments were fleeting and shots encircled the air. We ran. Reached the first position, advanced. A wave of dust and voices washing over us as we grasped the pavement and broke it. A few moments of

allahu akbar

*

mingling with the rustle of clothes against bodies. And then, everything was still. We were at the Bab Idriss intersection. Khaled was killed and three comrades wounded. It wasn’t grief so much as something else. When we gathered the following day to assess the battle, Jaber said: an excellent battle. I don’t remember much, but I kept shooting till the rifle ran dry. We were like lightning. As for Talal, he was still in a daze. Its like a film, like the movies. Next time, I’ll film it.

We were scattered across the buildings and the pavements. Feet soaked, bodies slippery, the drizzle coming and going. We’d carried the sandbags over from the ambush opposite which the Kataeb had abandoned. We’d built our barricades and sat down to eat. We were hungry but ate without appetite.

The surprise came in the afternoon. The positions were quiet and we heard only distant gunfire. Rifles at rest and we resting beside them, on our guard, looking into the distance where the enemy positions were. We were going over our memories of the battle, some true, some not, when we saw throngs of people approaching. Children with heads shaven and unshaven. Milling about the hide-outs, searchings for things in the rubble and in the shops. People of all sorts: Kurds, Arabs. … They were all there, with their women and their children.

— Impossible, I shout. We’re against looting. We’re here to protect the people, not to loot.

— What’s impossible is to stop them, Talal retorts, yelling at them to go away, firing a few shots in the air.

But they won’t go away. What’s this? What is this? Shapes and colors of all sorts bending over. This isn’t looting. This is folklore. This is a

’eid.

This is Revolution. All revolutions are like this. Beautiful and terrifying and …

In the throes of our surprise and amid everyone’s shouting to try to stop them, their numbers grew. They scuttled away from our shouting and firing only to come back. Then khaki began to mingle with the other colors. What’s this comrades? Whole groups of them were streaming in. They’d found out that the position had fallen. And had come to fight and loot and live.

— What do they want?

—That’s the sea for you. What’s the difference between people and the sea? What’s the difference between the sea and the fish?

The sea wasn’t the only surprise. As it spreads, war gets to be full of surprises. And after the fall of Maslakh and Qarantina

*

to the Fascists, the war itself became one big surprise. Vast numbers of fighters and militiamen, with their weapons, their boots, their clothes, filling the streets of Wadi Abu Jameel in ceaseless attempts to reach the sea. Practically speaking, coordination wasn’t possible. Joint and disjointed forces

**

from all over the country coming here to fight. The commander going from position to position, trying to coordinate — not an easy task. And we, fighting from position to position, from wall to wall, dust filling the air.