Little Mountain (2 page)

Authors: Elias Khoury

Nor is this all. Khoury is a highly perceptive critic, associated with the avant-garde poet Adonis, and his (now defunct) Beirut quarterly

Mawaqif.

Between them members of the

Mawaqif

group were responsible during the 1970s for some of the most searching investigations of modernity and modernism as applied to Arab culture; as explicator, critic, polemicist, translator, and formulator of new ideas, Khoury came to remarkable prominence while still in his 20s. It is out of this work, along with his engaged journalism — almost alone among Christian Lebanese writers he espoused the cause of resistance to the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon (see his book

Zaman al-Ihtilal, Period of Occupation)

and did so publicly and relentlessly at great personal risk from the heart of West Beirut—fiction, editing, translating, and literary criticism that Khoury has forged (in the Joycean sense) a national and novel, unconventional, fundamentally postmodern literary career.

This is in stark contrast to Mahfouz, whose Flaubertian dedication to letters has followed a more or less modernist trajectory. Khoury’s ideas about literature and society are of a piece with the often bewilderingly fragmented realities of Lebanon in which, he says in one of his essays, the past is discredited, the future completely uncertain, the present unknowable. For him perhaps the most symptomatic and yet the finest strand of modern Arabic writing derives not from the stable and highly replicable forms originally native to the Arabic tradition (the

qasidah)

or imported from the West (the novel) but those works he calls formless —e.g., Tawfik al-Hakim’s

Diaries of a Country Lawyer,

Taha Hussein’s

Stream of Days,

Gibran’s and Nuaimah’s writings. These works, Khoury says, are profoundly attractive and have in fact created the “new” Arabic writing which cannot be found in the more traditional fictions produced by conventional novelists. What Khoury finds in these formless works is precisely what Western theorists have called postmodern: that combinatorial amalgam of different elements, principally autobiography, story, fable, pastiche, and self-parody, the whole highlighted by an insistent and eerie nostalgia.

Little Mountain

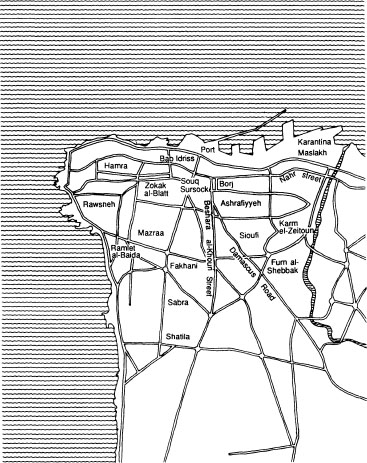

replicates in its own special brand of formlessness some of Khoury’s life: his early years in Ashrafiyyeh (Christian East Beirut, also known as the Little Mountain), his exile from it for having taken a stand with the nationalist (Muslim and Palestinian forces) coalition, subsequent military campaigns during the latter part of 1975—in downtown Beirut and the eastern mountains of Lebanon —and finally an exilic encounter with a friend in Paris. The work’s five chapters thus exfoliate outward from the family house in Ashrafiyyeh, to which neither Khoury nor the narrator can return given the irreversible dynamics of the Lebanese Civil Wars, and when the chapters conelude, they come to no rest, no final cadence, no respite. For indeed Khoury’s prescience in this work of 1977 was to have forecast a worsening of the situation, in which Lebanon’s modern(ist) history was terminated, and from which a string of almost unimaginable disasters (the massacres, the Syrian and Israeli interventions, the current political impasse with partition already in place) have followed.

Style in

Little Mountain

is, first of all, repetition, as if the narrator needed reiteration to prove to himself that improbable things actually

did

take place. Repetition is also, as the narrator says, the search for order —to go over matters sufficiently to find, if possible, the underlying pattern, the rules and protocols according to which the Civil War, most dreaded of all social calamities, is being fought. Repetition permits lyricism, those metaphorical flights by which the sheer horror of what takes place (“Ever since the Mongols … we’ve been dying like flies. Dying without thinking. Dying of disease, of bilharzia, of the plague. … Without any consciousness, without dignity, without anything.”) is swiftly seen and recorded, and then falls back into indistinct anonymity.

Style for Khoury is also comedy and irreverence. For how else is one to apprehend those religious verities for which one fights —the truth of Christianity, for instance —if churches are also soldiers’ camps, and if priests like the French Father Marcel in Chapter Two of

Little Mountain,

are garrulous and inebriated racists? Khoury’s picaresque ramblings through the Lebanese landscapes offered by civil combat reveal areas of uncertainty and perturbation un-thought of before, whether in the tranquility of childhood or in the certainties provided by primordial sect, class, or family. What emerges finally is not the well-shaped, studied forms sculpted by an artist (like Mahfouz) of the

mot juste,

but a series of zones swept by half-articulated anxieties, memories, and unfinished action. Occasionally a preternatural clarity is afforded us, usually in the form of nihilistic aphorisms (“The men of learning discovered that they too could loot”), or of beach scenes, but the disorientation is almost constant.

In Khoury’s writing therefore we get an extraordinary sensation of

informality

persuaded gently and not always successfully through the channels of narrative. Thus the story of an unraveling society is put before us as the narrator is forced to leave home, fights through the streets of Beirut and up into the mountains, experiences the death of comrades and of love, ends up accosted by a disturbed veteran in the corridors and on the platform of the Paris metro. The startling originality of

Little Mountain

is its avoidance of the melodramatic and the conventional; Khoury plots episodes without illusion or foreseeable pattern, much as a suddenly released extraterrestrial prisoner might wander from place to place, backward and forward, taking things in through a surprisingly well-articulated earth-language, which is always approximate and somehow embarrassing to him.

Finally of course Khoury’s work embodies the very actuality of Lebanon’s predicament, so unlike Egypt’s majestic stability as delivered in Mahfouz’s fiction. I suspect, however, that Khoury’s is actually a more typical version of reality, at least so far as the present course of the Middle East is concerned. Novels have always been tied to national states, but in the Arab world the modern state has been derived from the experience of colonialism, imposed from above and handed down, rather than earned through the travails of independence. It is no indictment of Mahfouz’s enormous achievement to say that of the opportunities offered the Arab writer during the twentieth century his has been conventional in the honorable sense: he took the novel from Europe and fashioned it according to Egypt’s Muslim and Arab identity, quarreling and arguing with the Egyptian state, but finally, always, and already its citizen. Khoury’s achievement is at the other end of the scale. Orphaned by history, he is the minority Christian whose fate has become nomadic because it cannot accommodate itself to the Christian exclusionism and xenophobia shared by other minorities in the region. The underlying aesthetic form of his experience is assimilation —since he remains an Arab, very much part of the culture — infected by rejection, drift, errance, uncertainty. Yet Khoury’s writing represents the difficult days of search and experiment now expressed in the Arab East by the Palestinian

intifadah,

as newly released energies push through the set repositories of habit and national life and burst into terrible civil disturbance. Khoury, along with Mahmoud Darwish, is an artist giving voice to rooted exiles and trapped refugees, to dissolving boundaries and changing identities, to radical demands and new languages. From this perspective Khoury’s work bids Mahfouz an inevitable and yet profoundly respectful farewell.

LEBANON

BEIRUT

MOUNTAIN

LITTLE

MOUNTAIN

They call it Little Mountain.

*

And we called it Little Mountain. We’d carry pebbles, draw faces and look for a puddle of water to wash off the sand, or fill with sand, then cry. We’d run through the fields —or something like fields —pick up a tortoise and carry it to where green leaves littered the ground. We made up things we’d say or wouldn’t say. They call it Little Mountain, we knew it wasn’t a mountain and we called it Little Mountain.

One hill, several hills, I no longer remember and no one remembers anymore. A hill on Beirut’s eastern flank which we called mountain because the mountains were far away. We sat on its slopes and stole the sea. The sun rose in the East and we’d come out of the wheatfields from the East. We’d pluck off the ears of wheat, one by one, to amuse ourselves. The poor—or what might have been the poor — skipped through the fields on the hills, like children, questioning Nature about Her things. What we called a

’eid

**

was a day like any other, but it was laced with the smell of the

burghul

and

’araq

†

that we ate in Nature’s world, telling it about our world which subsists in our memory like a dream. Little Mountain was just a tip of rock we’d steal into, wonderous and proud. We’d spin yarns about our miseries awaiting the moments of joy or death, dallying with our feelings to break the monotony of the days.

They call it Little Mountain. It stretched across the vast fields dotted with prickly-pear bushes. The palm tree in front of our house was bent under the weight of its own trunk. We were afraid it would brush the ground, crash down to it, so we suggested tying it with silken rope to the window of our house. But the house itself, with its thick sandstone and wooden ceilings, was caving in and we got frightened the palm tree would bring the house down with it. So we let it lean farther day by day. And every day I’d embrace its fissured trunk and draw pictures of my face on it.

We feared for the mountain and for its plants. It edged to the brink of Beirut, sinking into it. And the prickly-pear bushes that scratched our legs were dying and the palm tree leaning and the mountain edging toward the brink.

They call it Little Mountain. We knew it wasn’t a mountain and we called it Little Mountain.

Five men come, jumping out of a military-like jeep. Carrying automatic rifles, they surround the house. The neighbors come out to watch. One of them smiles, she makes the victory sign. They come up to the house, knock on the door. My mother opens the door, suprised. Their leader asks about me.

— He’s gone out.

— Where did he go?

— I don’t know.

— Come in, have a cup of coffee.

They enter. They search for me in the house. I wasn’t there. They search the books and the papers. I wasn’t there. They found a book with a picture of Abdel-Nasser

*

on the back cover. I wasn’t there. They scattered the papers and overturned the furniture. They cursed the Palestinians. They ripped my bed up. They insulted my mother and this corrupt generation. I wasn’t there. I wasn’t there. My mother was there, trembling with distress and resentment, pacing up and down the house angrily. She stopped answering their questions and left them. She sat on a chair in the entrance, guarding her house as they, inside, looked for the Palestinians and Abdel-Nasser and international communism. She sat on a chair in the entrance, guarding her house as they, inside, tore up papers and memories. She sat on a chair and they made the sign of the cross, in hatred or in joy.

They went out into the street, their hands held high in gestures of victory. Some people watched and made the victory sign.

We called it Little Mountain when we were small. We’d run along its dirt roads or on the edge of the asphalt which cut into our feet. We’d walk its streets looking for things to play with. And during the holidays, I’d go with my father and brothers to the fields called Sioufi and frolic between the olive and Persian lilac trees. There, we’d stand on top of a high hill overlooking three roads: the Nahr Beirut road, the Karm al-Zeytoun road

**

and the third one, which we called the road to our house. We’d stand on the high open hilltop, run through it and always be afraid of falling off onto one of the three roads.

He stood perched on the high hill. Holding his big father by the right hand, he’d watch the cars far away on the road below and marvel at how small they were. They weren’t like the car he rode to his uncle’s distant house. Very small cars, one behind the other, like the small car that his father bought him and set in motion by singing to it. There’s not a sound to these metal cars going by. Soundless, they move along regularly, one behind the other, in a straight line. They don’t stop. Inside are miniature-like people. They aren’t children of my age —he’d think to himself—and once, when he asked his father about the secret of the small cars, his father answered in the overtones of a diviner that the reason was that Ashrafiyyeh being a mountain, the Beirutis went and spent the summer there. And compared with Beirut, the mountain is high. The distance between us and the Nahr Beirut is high, like that between us and the Karm al-Zeytoun road. And the farther you are, the smaller things get. Later, when you grow up, you’ll see that the cars are very small. Because vision is also related to the size of the viewer. I would nod, feigning comprehension, not understanding a thing. Generally, I’d let my father tell me his story, which he always retold, about distances and cars and distract myself by chasing a golden cicada flitting among the green grasses or perched between the branches of the olive trees.

A long line of small soundless cars. We’d sit on the edge of the hill and watch them go by, waiting for the day when we’d grow up and see that they were very small really, or go down to the road and see that they were very big. They trickled by like colored drops of water of varying size. Trucks, petrol tankers, all sorts of small cars. We could tell the difference between them although we couldn’t name them or say what they were for. They were far away and small and wed hold each other by the hand waiting to grow up so they’d grow even smaller, wed hold each other by the hand and wait to understand the secret. And I always used to wonder how come cars were small just because they were far away and I would daydream about the stories of dwarfs they told us at school or of the man whom the devil turned into a dwarf, which my grandmother always told me.

Little Mountain where it was, the vegetation that covered its handsome mound was giving way to roads and we rejoiced at the opening of the first cinema in Sioufi. But surprises awaited me. We were growing and what we had been waiting for, so long now, didn’t happen. We were getting bigger, wed go to Sioufi to watch the cars—and see that they’d gotten bigger. We got bigger and the cars got bigger. Hemmed in by the gathering clamor and frenzy. We were getting bigger and the once-straight lines were curving, the clamor getting closer and the spaces narrower. I walk alone, Little Mountain twists and turns. I search for memories of when Palm Sunday

*

was a ’

eid

and we came out of the church to the sound of Eastern chants: I find only a small, neglected picture in my pocket.

Cars growing, closing in on me. Trees shrinking, disappearing. I was growing bigger and so were the cars, around my neck were their sounds, their colors, their sizes. Now, we can tell the difference between them but we don’t understand.

Old expectations and distant memories are merely expectations and memories. At night, the cars climb the three roads to the high hilltop. Bruising my eyes, their lights encircle me. The whine of the engines walling me in as they approach my face. The cars are big, they have huge eyes extending filaments of fire that don’t burn. They leave the traces of terror, of questions and answers, on my face.

The cars were growing—and we were growing. The broad streets were growing and the trees bent low on Little Mountain. What has become of my father’s explanations as he told me stories of distance and height and size?

You stand alone amid the flood of lights that blinds you and robs you of your memory. You go looking for your house, alone, memoryless.

Abu George told me the story of the names. Abu George has been my friend since the time I wandered around Little Mountain, alone among the lights, looking for my father’s explanations. He’d find me alone, sitting on the edge of a hill overlooking the railroad tracks of the slow train that stands out in my memory, and would tell me his stories of the French and the world war.

He’d relate how Sioufi used to be a huge property owned by a man called Yusef as-Sagheer.

*

That is why Ash-rafiyyeh was called Little Mountain. Then, the brothers Elias and Nkoula Sioufi bought it up dirt-cheap and, after World War I, they built a furniture factory on it. The neighborhood came to be known by their name.

The factory, in reality a large workshop, was an event in itself. It had about fifty workers. They built themselves some shacks nearby, and a small cafe serving coffee and

’araq

opened next door. The factory was a novel sort of undertaking and people began getting used to a novel way of life, for the first time. Modern machines. European-style furniture. They knew neither where it went nor how it would be sold. They collected their wage—or something like a wage —at the end of the month, gave some of it to their women, and drank

’araq

with the rest.

As the neighborhood got used to this new kind of life, there arose a new kind of theft. Instead of the old kind of robberies —like those of a man called Nadra who lived at the eastern end of the neighborhood and who, in the ancient Arab tradition of chivalry, extorted money from the rich to give it to the poor—-there was now organized robbery. Gang robbery, premeditated and merciless; without a touch of chivalry or any other kind of principle. The most important event which established this new-style thieving was the robbery of the Sioufi factory itself. At the end of each month, the accountant would go to Beirut to fetch the workers’ money and come back to the factory to distribute it to them. Once, at a crossroads, some thieves ambushed him; they took the money and left him there, hollering. Alerted by his screams, the workers gathered around. Men, women, and children rushed out and chased the thieves. The thieves ran and people ran behind them, popping out of the dirt roads and alleys. Before anyone had caught up with them, the thieves stopped running, threw the coins to the ground and resumed their race. At that point, bodies doubled up over coins and hands started snatching. People forgot the thieves and let them get away, snatching up the coins from the ground helter-skelter. It was no chivalrous kind of theft, Abu George would say. Why? Because they all forgot their honor and made for the coins. They were lenient with the thieves and took the factory’s money. That is when the decline set it. And the story has it, the factory started going bankrupt then, Abu George would continue. Elias Sioufi died of a broken heart and his brother, Nkoula, sold off the property to the people of the neighborhood. And it was split into small holdings.