Listening In (7 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

Another imperfection is that it is highly difficult to transcribe all of the words with perfect accuracy. It is a slow and painstaking labor to recapture a conversation, especially when several people are talking at once, from different parts of the room. The transcripts here have attempted to eliminate errors, but it is important for readers to remember that even these transcripts represent a best guess at the words spoken. The National Archives considers the official document the tape itself and not any transcript made from it. In this publication, imperfectly heard words will be placed within brackets, or the word “unclear” will be added.

The organizing principle of this collection has been to offer a wide range of Kennedy’s meetings and telephone calls. Needless to say, the major episodes are included, and readers will not be surprised to see selections from the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Civil Rights Movement here, including one brief excerpt from the Missile Crisis that has never before been released. But there are other topics included as well, to show the breadth and depth of the Oval Office conversations, and the vaulting ambition of this presidency, which launched a failed invasion of Cuba, then prevailed in the most dramatic nuclear confrontation in history, then succeeded in seriously limiting the testing of nuclear weapons, all while launching the space program, quickening the economy, nurturing a post–Cold War foreign policy for the developing world, and presiding over a dizzying array of social and technological advancements, the most historic of which was the struggle to give all Americans equal access to their rights.

There is laughter in these conversations, and irritation, and disappointment, and exuberance. In a word, they are human. We perhaps expect our presidents to be something greater than that; but these recordings will remind us, healthily, that real people work in the Oval Office. Some of the most evocative phone calls reveal the special relationship that exists between members of the tiny club of fellow presidents. Kennedy and Eisenhower could not have been more different, but the thirty-fourth president’s advice was obviously important to the thirty-fifth, especially at times of immense military peril. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Eisenhower’s support was invaluable and helped Kennedy to calm waters that had become dangerously roiled. Further, they seemed to grow fond of each other. One of their crisis calls ends with Kennedy signing off, “Hold on tight!”

Kennedy once said, “I expect my whole time in office to be filled with dangers and difficulties,” and his prophecy was soon fulfilled. The most dangerous moment of all, the Cuban Missile Crisis, lends itself well to an audio approach to history; nearly all of the major meetings were recorded in their entirety, and many phone calls, including Kennedy’s relieved calls to Presidents Eisenhower, Truman, and Hoover when it was over. To listen to these meetings and calls is to hear that crisis unfold in real time, in a way that no history book can recapture. Likewise, there is a remarkable drama to the story of the Civil Rights struggle in these years, from the Freedom Rides in the spring of 1961 (before the taping began) to the crises in Mississippi and Alabama in 1962 and 1963 (fully captured in arresting detail). The tapes record complex negotiations with recalcitrant governors and reveal some of Kennedy’s exasperation at being pulled down a path that he knows will inflict a punishing political cost, including the possibility of a single term. It was a slow and often frustrating path, for all parties involved, including the liberals who longed for Kennedy to become a great champion of their causes (though they had often failed to support him in the past). But the tapes also record his growing conviction over 1963 that the time was right for a great moral crusade and that he was uniquely fit to lead it. In all of these meetings, the vocal inflections say more than the words do; one can hear Kennedy’s insistence that Governor Ross Barnett of Mississippi obey the federal writ, and Barnett’s grudging acquiescence. We can hear the anger in the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., not far below the beatific surface of “I Have a Dream.”

One day in particular—August 28, 1963—shows how many of these topics overlapped in that turbulent time. Shortly after King gave his great address during the March on Washington, the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement were ushered into the Oval Office for an extraordinary strategy session. In that meeting, A. Philip Randolph, the aging head of the Brotherhood of Railway Porters, called on Kennedy to assume the mantle of presidential leadership. That moment is all the more evocative for the knowledge that Randolph was captured on tape in one of the earliest recordings ever made in the Oval Office, way back in 1940, as a young man saying more or less the same thing to Franklin D. Roosevelt. This time, as an old man, his message got through, and the President responded with a long discourse on the political path ahead, and the votes that would need to be rounded up—another way of saying that at long last, the plan was going forward.

About six hours earlier, a long noontime meeting about Vietnam tried to salvage U.S. policy in Southeast Asia, with far-reaching consequences. It can be dizzying to realize the range of issues that were pressing upon the Oval Office with hourly urgency. As protected as the White House may seem, it was never that far away from the street, and I thought, by listening hard, that I could hear the sound of the marchers going down the Mall, demanding civil rights, even as the Vietnam meeting was unfolding. Much of the subsequent history of the 1960s was written inside that room, on that single afternoon.

Of course, not all of the topics discussed have the same epic sweep. I tried for topicality with these selections, but they represent only a tiny percentage of the total recorded output. It may surprise students of other presidencies to realize how deeply JFK delved into policy matters that would seem, at first glance, to be sub-presidential. The meetings cover a wide swath of federal governance, from the deeply domestic concerns of local politicians, to the international events that so clearly absorbed Kennedy, to the distant reaches of outer space. Relentlessly, he grilled his advisors on the effects of policies, their vulnerabilities, and the need for follow-up action. Part of his mind was always occupied with the challenge of getting his expansive agenda through Congress, for there was little point in adopting idealistic positions if they had no chance of succeeding. Many of these meetings record that process, winning over senators one vote at a time. But at the same time, there was constant pressure to think beyond Washington and set in motion the enormous engine of the United States government, at home and around the world. Kennedy must have frustrated the State Department nearly as much as it frustrated him, with long meetings about every corner of the earth, often with foreign ministers and ambassadors of other countries who must have been astonished to be speaking directly to the leader of the free world.

Clearly, he loved the job, and loved it precisely for the chance it gave him to translate thought into action. Kennedy called the presidency “the vital center of action in our whole scheme of government.” These conversations reveal a man very much inside that center. “The presidency is the place,” he says to his dinner party companions in the tape of January 5, 1960, that appears near the beginning of this book—and then over and over again: “it is the seat of all power,” “it is the center of the action,” and “it’s the President who really functions.”

These tapes eminently bear out that theory. His vigor—to borrow an overused word of the era—is palpable. There he is, urging his advisors to work harder and think better, impatient with lazy answers. He drives the meeting forward, tapping his fingers, asking clipped questions, shaving away irrelevancies like a carpenter with a lathe. Or when making a phone call, he speeds up the other speaker with staccato “yeahs,” until a terminal “righto” ends the call abruptly. Sometimes, when a slower speaker has the floor (Averell Harriman, for example, or Dean Rusk), one can sense Kennedy’s impatience.

When asked, during that same 1960 dinner party, why he would urge a young college student to go into politics, he answers that “it provides an opportunity for him to participate in the solution of the problems which interest him.” It was an understated way of saying that politics gave him a chance to answer the great challenges of his time, and perhaps to achieve the Greek definition of happiness which he often quoted—“full use of your powers along lines of excellence in a life affording scope.” The stakes were big. So were the rewards, but so too were the difficulties. In an age that has become far more cynical about politics and politicians, there is something encouraging about the zeal with which Kennedy and his staff tried to tackle the problems they encountered.

The Kennedy management style can certainly be criticized for unorthodoxy. He favored restless intellects like his own, and those who would argue with him—as James Webb, the head of NASA, does in one of the meetings. It was well known that he disliked the buttoned-down approach of the Eisenhower White House, with carefully groomed meetings and few disagreements. Bluntly, he said, “Cabinet meetings are simply useless. Why should the postmaster general sit there and listen to a discussion of the problems of Laos?” The result is that these Oval Office bull sessions were all the more important for shaping the course of the New Frontier. And they seem, on the face of the evidence, to have generally shaped it well. Not all of these meetings resulted in favorable outcomes. Vietnam presented Kennedy with an array of possible outcomes, all unattractive, in the fall of 1963, and he was deeply troubled by the violent coup of November 2, as a privately recorded dictation in this collection indicates. Another private reflection, from around November 12, indicates that his support for Civil Rights was already raising alarm bells about his reelection prospects. So there were dark clouds on the horizon. But still, the record, as conveyed by these working conversations, is one of a presidency adapting aggressively to the demands of the times and leading the nation forward, exactly as the 1960 campaign had promised to do.

As a student of the past, Kennedy knew well that presidential reputations are variable and depend on a wide range of factors, many of which are beyond the control of the office. In irritation, he once complained to Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., whose father (Sr.) had pioneered the presidential ranking system we now cannot escape, “How the hell can you tell? Only the President himself can know what his real pressures and his real alternatives are.”

Kennedy continues to do very well in those rankings, but for reasons that would probably irritate him, or at least touch upon his finely honed sense of irony. He deplored helpless sentimentality, which is exactly what we bring to the memory of our presidents, and to him in particular. He admired unblinking realism, which is in as short supply now as it was then. Critics will point out that he benefited handsomely from well-managed publicity campaigns throughout his career, and after, with a nostalgia for Camelot that has never lost its power, even a startling half century after the fact. But the creation of these tapes in 1962, and their final release in 2012, has done much to sweep away the sentiment and restore the substance that was at the heart of this presidency.

Mythology exists for a reason; we tell ourselves stories to explain complicated subjects, and the presidency of the United States is nothing if not complicated. But in the final analysis, John F. Kennedy preferred history, because its verdicts emanate from facts. The public has a right to as full an accounting from the past as it does from the politics of the present—the mistakes as well as the successes. Thanks to these recordings, and the completion of the fifty-year process that led to their release, a fuller accounting is now possible. We will never know all of the reasons that President Kennedy established this remarkable repository of recorded information. But we can take solace that he did. I hope that readers enjoy this opportunity to listen to these dialogues, from the innermost chamber of the republic, unfiltered and immediate.

The Yale speech that I began with went to the core of the matter:

For the great enemy of truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived, and dishonest—but the myth—persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the clichés of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.

Now, thanks to these tapes, readers can move past the myth, and judge the essence of a presidency for themselves.

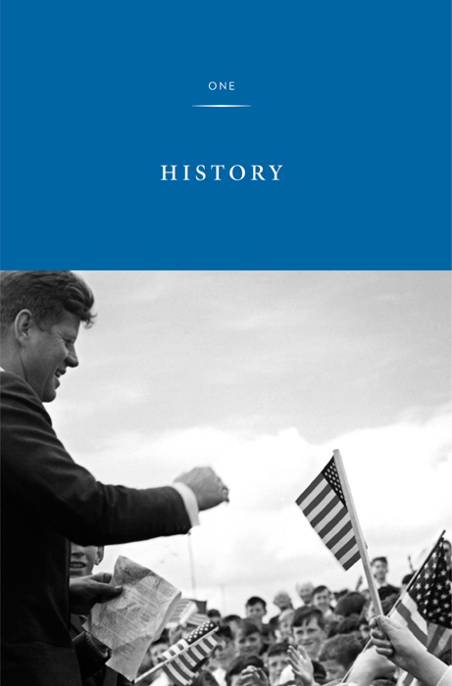

PRESIDENT KENNEDY IN NEW ROSS, IRELAND, JUNE 27, 1963