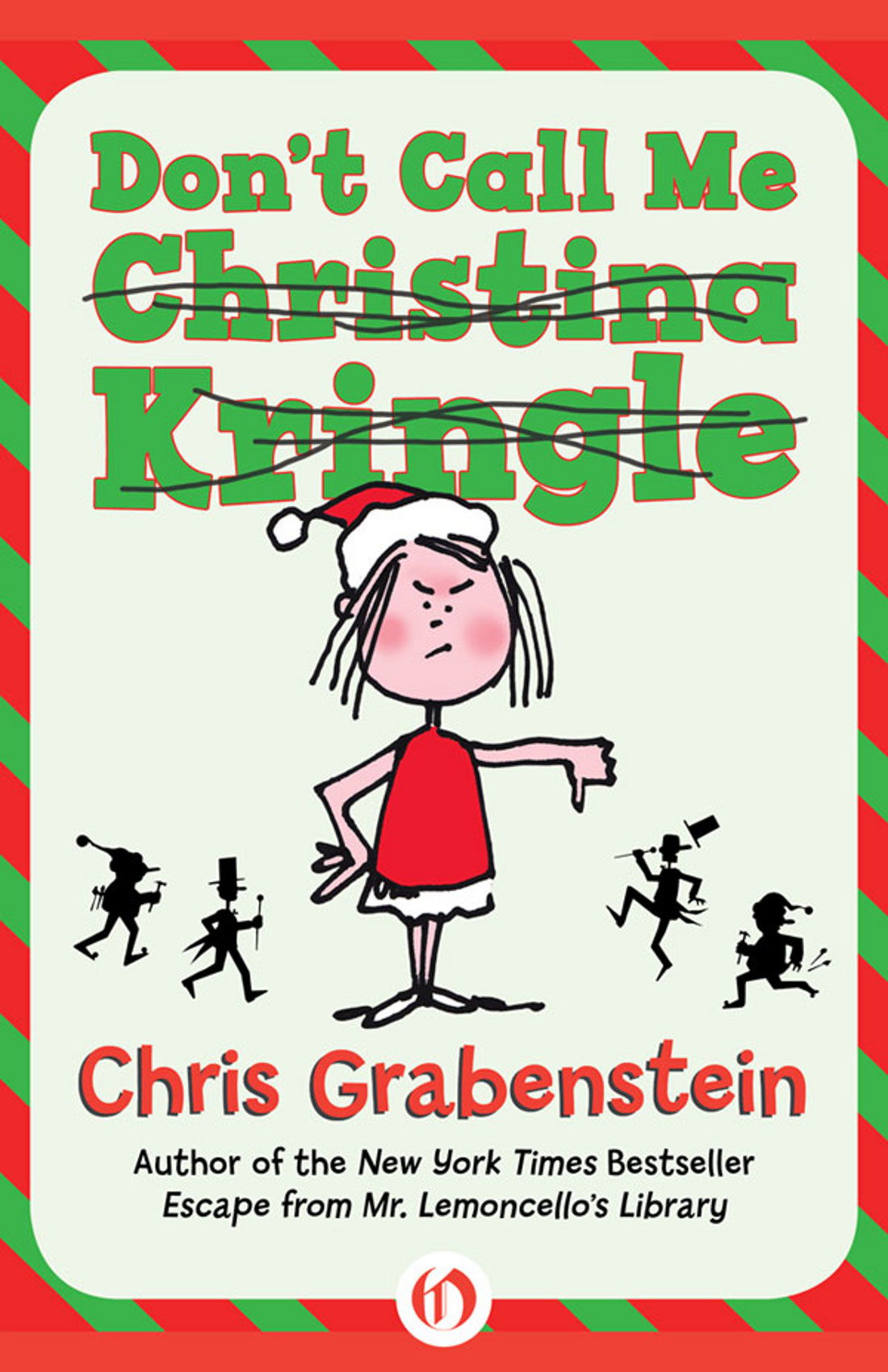

Don't Call Me Christina Kringle

Read Don't Call Me Christina Kringle Online

Authors: Chris Grabenstein

Chris Grabenstein

Contents

ContentsPrologue

There were things people knew a long time ago, before everybody got so much smarter.

They knew who painted the leaves every autumn and who sugared windowpanes with frost come winter. They knew who could take a pile of wood chips and turn it into a mountain of golden coins.

When they saw trampled patches in the dewy morning grass, they knew whose tiny feet had been dancing in the moonlight and why they had heard faint fiddle music drifting on the breeze.

They also knew darker thingsâlike who could make milk curdle or a lake jump its banks to flood a village.

Everybody knew these things. Kings and queens and even Shakespeare.

Then, everyone forgot.

Well, almost everyone. Our story begins with one man who remembered far too much. â¦

McCracken was a droopy giant of a Scotsman.

He stood nearly seven feet tall and had a floppy mop of carrot-orange hair that he wore like a fuzzy slouch cap on top of his head.

He was so tall he had to duck to avoid doorjambs, lighting fixtures, and the occasional overhead sprinkler spout. As a consequence, McCracken's spine was permanently bent to the left in a lazy, loopy curve. When he walked, he loped alongâslowly lifting one long leg, bending one knobby knee, bringing down one half of his lanky bones onto one size-fifteen foot, and then, repeating it all on the second side. Skulking about like a felonious flamingo, Donald McCracken always looked like he was up to no good, which, in fact, he usually was.

This particular morning, nearly a month before Christmas, McCracken was loping through a concrete cavern of dusty floors, steel pillars, greasy machinery, and idle conveyor belts. A factory. A candy caneâmaking factory, to be precise. McCracken had been summoned here on Thanksgiving morning because the factory should have been bustling with activity.

But it wasn't.

It should have been noisy with the clack of cogwheels, the grind of gears, and the sharp thwack of candy being wrapped with clear and crinkly cellophane because Christmas was only thirty days away and Christmas is the number-one candy caneâselling season of the whole year.

But the factory was silent.

No machines clanked. No conveyor belts whirred. The grease on the cane-wrapping equipment was cold and lumpy.

A short, nervous man resembling a pudgy chipmunk in a business suit escorted McCracken across the factory floor. The little man paused to sponge the moisture off his bald dome. He used the tip of his necktieâsomething he probably should've done with a handkerchief. Maybe a towel. Or a mop. But the chipmunk man, who owned the candy-cane factory, was too nervous to do what he should've done. If candy canes didn't start rolling off his assembly line soon, he would be ruined. If he couldn't churn out candy canes during the peak of the candy cane-selling season, he'd lose everything. His money. His factory. The warehouse. His house. His wife and children, too, because they liked living indoors and eating food and wearing clothes and having cable television, all things that cost money! So even though the factory was chilly (he had long since turned off the heat) the little man had sweat pooling under his arms and trickling down his back. And B.O. The little man was a mess. He pointed to a rolling canvas bin parked at the end of one conveyor belt.

“Take a look,” he said to Donald McCracken. “No stripes! No red swirls at all! Something's wrong with the striper machine!”

McCracken's thick lips curled up into a sinister grin as he gazed down at a heaping pile of blank candy canes. Curl-tipped walking sticks made out of hard white sugar without any peppermint swirlâhundreds of them pyramiding on top of each other.

“Nobody wants candy canes without stripes!” the little man stammered. “I'm ruined! Ruined!” He blubbered some more, then blew his nose in the only cloth he had handy. His tie again. Perhaps his wife would give him a new one for Christmas. One that wasn't green.

McCracken shook his head and clicked his tongue.

“Pity,” he said in his thick Scottish brogue. “Terrible pity, indeed.”

“Terrible? This is horrible! My striping machine is broken and I don't know how to fix it because the instruction manual is written in German, which I never learned how to read because I was too busy counting my money, the money I made making candy!”

McCracken smiled. Then he started singing a snatch of his favorite Christmas carol: “

Christmas is coming, the goose is getting fat, please put a penny in the old man's hat. ⦔

Since he didn't have a hat, just all that orange hair, McCracken held out his hand.

“I'll write you a check,” said the frazzled factory owner. “I'll write you a check right now!” He ripped a check out of his checkbook and scribbled an astronomical sum into the little box.

McCracken held up the check for a moment, admired the amount of money he was about to make, then tucked the thin slip of pink paper into his pocket.

“Now don't ye worry no more, Mr. Kasselhopf,” he said. “Just go home and go to bed.”

“Bed? How can I sleep?” The factory owner tugged at what little hair he had left, two clumps fringing his ears.

“Don't fret, laddy,” said McCracken. “Why tomorrow morning, when you come into your factory, you'll find mountains of red-and-white candy canes waiting for you; that I promise.

Mountains!

Every bin full. Now run along, laddy boy. Leave me be. â¦

”

“Butâ”

“Leave me be!”

Donald McCracken waited until the terrified (and somewhat smelly) little man was gone.

When he heard the factory doors slide shut, he marched over to where he had stacked his boxes.

McCracken had only brought six wooden crates tonight, figuring six would be more than enough for the job at hand. The boxes, made of rough pine boards and each with a small barred door at the front, were approximately one foot long, one foot deep, and one foot wide. The side panels were stenciled and stickered with labels: “LIVE PETS.” “HANDLE WITH CARE.” “IMPORT OF SCOTLAND.” “THIS END UP.” “MIND YOUR CREAM.”

McCracken took the six crates and spaced them out evenly alongside the factory's main conveyor belt. As he placed the boxes on the floor, he flipped open their tiny doors. Attached to the bars in each door panel was a miniature plastic cup, the kind you'd see in birdcages at the pet store. McCracken filled the miniature containers with heavy cream poured from a thermos bottle he kept stowed in his woolen overcoat.

While he loped his way down the line of shipping crates, the lanky Scot kept mumbling his favorite holiday song:

“If you haven't got a penny, a ha'penny will do. If you haven't got a ha'penny ⦔

He pausedâjust long enough to change a few words:

“No wee ones for you!”

Christina Lucci was ten years old and absolutely, positively hated Christmas.

She hated the twinkle lights and the stupid songs and the reindeer with their big red schnozzles and the sugar cookies shaped like snowmen, even though it was kind of fun to bite off their hats and chomp on their heads. She hated tinsel on trees, holly wreaths, and angels who were heard on high. She hated eggnog. She wondered what eggnog was. There were certainly no eggs in it and what the heck was a nog, anyway? She suspected eggnog was really cream of mushroom soup disguised with yellow food coloring, then seasoned with nutmegâand she hated cream of mushroom soup almost as much as she hated Christmas. If she ever had visions of sugarplums dancing in her head, she'd go see a doctor. Maybe a psychiatrist.

More than anything else about the horrible holiday, she hated Santa Claus. The jolly fat man. Saint Nick. The roly-poly tub of lard. Mr. North Pole. As far as Christina was concerned, Santa was a sham, a scam, and a borderline diabetic (on account of all those cookies he shoveled into his face during one twenty-four-hour Christmas Eve eating binge). Santa was a fat slob with terrible taste in clothes (red fur-lined pajamas, a goofy night cap, rubber boots, and a thick black plastic belt? Who dressed this guy?). Santa was basically a creepy prowler who broke into homes, parked reindeer on roofs (where they probably pooped), swilled milk that had been sitting out for hours, and stuffed ratty old stockings with candyâas if anybody really wanted to eat candy that came out of a sock.

Santa was the main reason Christina Lucci hated everything else about Christmas.

She hated Santa first and foremost.

Hated him, not for anything he had given her but for what he had taken away.

On the other hand, Christina's grandfather, Guiseppe Lucci,

loved

Christmas.

NoâGuiseppe adored it. He lived for it. He waited all year for Thanksgiving to roll around because it meant he could finally haul out his Christmas crap and decorate his shoe repair shop, a tiny store, barely eight feet wide and maybe twenty feet deep that was squeezed between two bigger buildings in what was probably meant to be the entrance to an alleyway.

Christina helped out behind the counter at Giuseppe's Old World Shoe Repair Shop on weekends and school holidays. She didn't mind working. Helped the holidays seem shorter. Time flies when you're busy taking claim checks and handing people re-heeled shoes bundled up in string-tied butcher paper.

But time drags when you're forced to watch your grandfather drag another plastic figurine up out of the basement and into the shop's tiny window display. The window covered the four feet of storefront not occupied by the door.

“I love Rudolph!” Christina's grandfather said as he plugged in the power cord to yet another light-up statue with a bulb stuck in its belly. This one was a plastic reindeer missing a few antler nubs. “See his nose? You could even say it glows!”

Guiseppe laughed and Christina rolled her eyes.