Listening In (15 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

MEETING WITH VICE ADMIRAL HYMAN RICKOVER, FEBRUARY 11, 1963

Hyman Rickover had one of the most storied military careers of the twentieth century. Born in Poland in 1900, he emigrated with his family in 1905, at the time of anti-Jewish pogroms, and grew up in New York and Chicago, where he graduated from John Marshall High School and won admission to the United States Naval Academy. So began a remarkable naval career encompassing sixty-three years of active duty, marked by administrative ability, tireless work, and extremely independent judgment. Rickover served on submarines in particular and over the course of the 1940s and 1950s became the legendary “Father of the Nuclear Navy,” known for his technical expertise, his strategic wisdom, and his personal interest in interviewing thousands of officer candidates. One of them, Jimmy Carter, later claimed that Rickover was the greatest influence on him after his parents. Rickover gave President Kennedy a plaque that he displayed on his desk in the Oval Office, featuring the words of an old Breton fisherman’s prayer: “O God, Thy sea is so great and my boat is so small.”

Unusually, for a Cold Warrior on the front lines, Rickover was fascinated by education and the role it played in bettering society. In 1960, he published

Education and Freedom,

which announced that “education is the most important problem facing the United States today” and called for a “massive upgrading” of academic standards. Two years later, he published a detailed comparison of American and Swiss schools, arguing that the United States was inferior in nearly every respect. In this conversation with Kennedy, he took advantage of a presidential audience to press his point, dexterously comparing Kennedy’s privileged upbringing with his own as a first-generation immigrant.

MEETING WITH VICE ADMIRAL HYMAN RICKOVER, FEBRUARY 11, 1963

JFK:

I was just reading this rather good article in the

Baltimore Sun

this morning about school dropouts, in Baltimore and some of these other cities, what percentage they are, and why. A rather large percentage is lack of interest and so on. Now, why is it that children seem, particularly on television, and having exposure to the affluent society, why is it that it isn’t drilled into them, a sufficient sort of competitive desire … [to this rather rich]?

RICKOVER:

I’ll tell you, you can take two opposite extremes, you can take my case and you can take your case. In your case, you had parents who recognized that money can do you a great deal of harm. And they took care to see, dammit, that it did not. That’s because you had intelligent parents. In my case, I was brought up where, a lot times we didn’t have enough to eat; you had to go out and fight, and so one recognized the importance of school. I think it’s something like that. Now when you get in between, that’s where you have your problems.

JFK:

What I think of, how drilled into my life was the necessity for participating actively and successfully in the struggle. And yet I was brought up in a luxurious atmosphere, where this was a rather hard lesson. And you, from your own life …

RICKOVER:

Your parents were exceptional in this respect. The vast majority of parents who have children now [unclear] are just trying to do everything they can to make everything easy. In that way they are really defeating what they are trying to do.

JFK:

If you think that it’s built into everybody, a survival instinct, which there is, …

RICKOVER:

You know I do! You know it. You know it. Because everything is made easy for them. Some of them get to expect, your parents will take care of you. So you have youngsters going off and getting married. And fully expecting that the parents, you know, will come to their support. And they do. I can give you any number of cases like that, where the parents would have done much better for their children to throw ’em out. There comes a time in every animal life—and human being is a form of animal life—when you have to fend for yourself. This is where the trouble is. Today you can make these arguments today and society will support you. That never used to be the case before. This is the problem we have to face, and we have to try to get around it. Now excuse me if I’m taking up your time, you’re the busiest man in the world.

JFK:

Well.

RICKOVER:

I don’t want to get on all my ideas. But I have thought that if you really wanted to do something for this country, you will [hit on?] education. Because without education, you can’t do it.

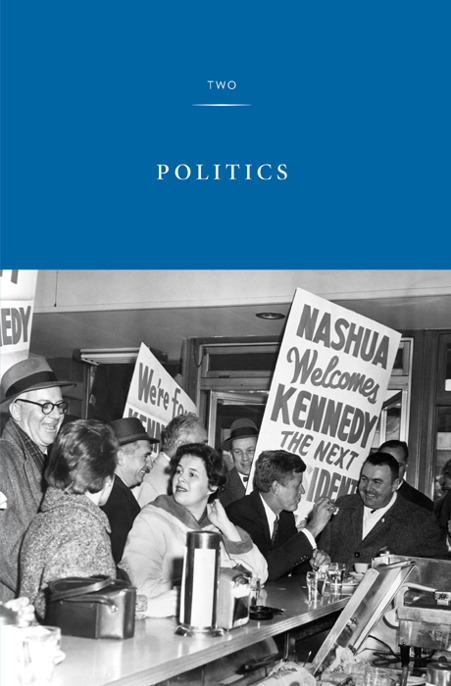

SENATOR JOHN F. KENNEDY STOPS TO EAT IN A DINER IN NASHUA, NEW HAMPSHIRE, DURING THE NEW HAMPSHIRE PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY CAMPAIGN, MARCH 5, 1960

A

fter losing the nomination for vice president at the 1956 Democratic Convention—the only loss of his career—Kennedy declared, “From now on I’m going to be the total politician.” He courted old-school political bosses and new-school television executives; he built relationships around the country and became a formidable presidential candidate in 1960. Despite his earlier claim, in his 1960 dinner-party tape, to be temperamentally challenged, he clearly relished politics, in defiance of a rising 1950s sensibility that disdained backroom deals as a regrettable price to pay for democracy. President Eisenhower once said, “The word ‘politics,’ I have no great liking for that.” Kennedy responded, “I do have a great liking for the word ‘politics.’ It’s the way a president gets things done.”

It was in pursuit of politics that Kennedy took to the phones with the zeal that he did. He conducted a great deal of business by telephone; congratulating governors, senators, and representatives when their fortunes were high; comforting them when they were low; and cajoling them for their help when he needed something done. This last he did often, as he drove forward the agenda of the New Frontier, often in the face of fierce headwinds. Even after winning the presidency and a Democratic majority in 1960, he had to deal with an obstructionist Congress that included Republicans and conservative Democrats, among them the “boll weevils” (Southern conservatives), who tied up most of the important committees. Many of these calls reveal democracy in action, as a president does what he can to nudge a bill forward, alternating between charm and political hardball. Despite the obstacles, the Kennedy administration proposed 653 pieces of legislation in its first two years, almost twice Eisenhower’s rate, and 304 became law.

If politics was changing because of Kennedy, it was also changing in spite of him; or more specifically, because the change that he represented encouraged many others to alter the status quo, in ways that did not always advance his political fortunes. An enormous number of voters would leave the Democratic Party because of its position on Civil Rights, or simply because they had moved out to the suburbs and had new priorities. But Kennedy’s adroit command of the issues, savvy use of television, frequent press conferences, and nimble outreach ensured that his popularity remained high.

CALL TO GOVERNOR EDMUND BROWN, NOVEMBER 7, 1962

The Democrats held their own in the midterm election of 1962, picking up two seats in the Senate and losing four in the House. A notable loss for the Republicans occurred in California, where Richard Nixon, fresh from his presidential defeat in 1960, lost in the gubernatorial race to Edmund “Pat” Brown by nearly 300,000 votes, despite leading in the polls before election day. JFK called in his congratulations to Governor Brown, and midway through the conversation, spoke to the governor’s son, Edmund “Jerry” Brown. Jerry Brown succeeded his father as the governor of California, winning election in 1974 and again in 2010.