Life on Wheels (62 page)

Authors: Gary Karp

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Physical Impairments, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Health & Daily Living, #Medical, #Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, #Physiology, #Philosophy, #General

Whatever type of armrests you choose, it is important to adjust them to the correct height. Armrests that are too high will lead you to elevate your shoulders, which can cause tight muscles and pain in the neck and shoulders. If armrests are too low, you will be encouraged to slump to the side to make contact, increasing the risk of developing spinal curvature.

Clothing Guards

Clothing guards—also called side guards—protect clothes from being soiled by or getting caught in the wheels. They are optional, but, if you will be riding your chair outside very much, clothing guards are a practical choice. If you live in a rainy environment or a place where it snows, these are mandatory equipment. Some armrests have built-in clothing guards. Those people who do not use armrests, or who prefer the tubular type that include no side panel, can use separate side guards. Clothing guards can be made of fabric, plastic, or metal.

The advantages of using cloth side guards are that they are lightweight and can be easily loosened when you need to move them out of the way, during transfers, for instance. The disadvantages are that the flexibility of cloth side guards makes them tend to bend outward from general use. When this happens, your clothing will not be completely contained.

Since plastic side guards do not get crushed down as the cloth ones do, they are more effective in holding in your clothing. The main disadvantage of plastic side guards is that they require extra care during transfers. You can injure your skin by hitting the hard edge, potentially causing a sore. You might also break the side guard. Finally, plastic guards can be an obstruction if you sometimes sit cross-legged in your wheelchair.

Maintaining Your Wheelchair

Whether you can physically work on your chair or not, it is extremely valuable for you to have at least some basic knowledge about the way it is put together and how it functions. The better you understand how your chair should be working—including how it should feel and even sound—the better you are able to notice early signs that something might be going wrong. This can mean the difference between a simple, inexpensive repair and a serious breakdown that could severely limit your mobility, have you waiting potentially months for a part, and cost a great deal of money. If you can’t handle tools on your own, then you can ask someone else to do it under your guidance.

Your chair should feel solid. If a nut and bolt are getting loose, you’ll feel a little bit of movement in the frame, for instance, which can put great stress on the overall structure of your chair and lead to significant damage. A squeak or any unusual sound or vibration can also indicate something on the verge of breakdown. The better you make note of how your chair feels when it is maintained and well-adjusted, the better you’ll be able to catch situations that can be dealt with easily.

Power chair users should know where connections go—for the batteries and for the control unit. This can also be handy at an airport if your chair arrives back at the airplane door with something in the wrong place. Since power chairs have more parts than a manual chair, more things can potentially go wrong, so knowing your chair is of even greater value.

For manual chair users with the dexterity (and tinkering aptitude), basic skills like being able to change tires, tighten up a sling seat or adjustable back, and clean and adjust brakes are very useful. Everybody should have an air tank or small battery-operated pump on hand to keep tire pressures full.

Your chair is a vehicle and, because it is customized to you and your needs, is simply not replaceable during a period of disrepair or being “in the shop.” It’s just like a car—you should take good care of it with regular basic maintenance and not delay getting it attention whenever something doesn’t seem right.

Wheeling Style and Technique

It is the nature of the body to become highly coordinated simply from the act of doing—the more you perform a particular task, the better your nervous and muscle systems integrate the very fine movements and myriad decisions that add up to mastery. Wheeling becomes as natural and second nature as walking. All of us can remember learning a skill that was awkward at first, whether it was tying shoes, playing a musical instrument, or cutting vegetables. This “practice-makes-perfect” principle applies to driving your wheels.

Optimal Wheeling

In order to become adept at maneuvering your wheelchair, you need the right chair, properly adjusted for your needs and well-maintained. Time and practice will lead naturally to expertise in how you and your chair move through space. Style and grace will distinguish you as a true master of your wheels.

Need for Speed

Faster isn’t always better, for the obvious reason that you could be thrown from your wheels. Too much speed makes it harder to control the chair, as you must brace your body against the various forces and sheer momentum of traveling so fast. Turning corners at high speed is a maneuver of extra risk, with centrifugal forces trying to keep your body going straight as you turn the chair.

Some manual chair riders wheel quickly to demonstrate their dexterity and agility to the outside world:

Looking back, I can see how much I was invested in being the hotshot wheelchair rider in the early years of my disability, which happened when I was a teen. Wheeling slowly somehow made me feel more disabled, a purely psychological response to how I imagined the public saw me. Surely, I seemed to think, if they see how agile and strong I am with my wheels, they won’t think I’m a “cripple” and everything I imagined to be associated with that image.

Although it’s only human to consider how others perceive us, it doesn’t really matter what others think or what their cultural assumptions might be in regard to disability. If your first concern is how you appear to others, then you are less focused on where you’re going and are using your body inefficiently, making you more likely to bump into something or jam a thumb on the brake.

For manual chair wheelers, frenetic wheeling wastes energy, is more fatiguing, and even puts the body at risk, such as for developing shoulder tendonitis. If you allow brief breaks between pushes, bringing your arms back in an unrushed manner, you will do fewer pushes for the same distance and expend less effort. A well-adjusted chair with well-inflated tires will coast more easily, helping ensure that you won’t have to exert yourself unnecessarily.

By taking your time, you also reduce the cumulative strain on your shoulders, elbows, and wrists, which could ultimately cost you the ability to use a manual chair. Some people who are aging with disabilities are losing the ability to push a manual chair. Slow down just a bit, and you will have more grace and more energy for your day and will preserve independence throughout your lifetime. You can certainly still have fun in your wheels.

I have a favorite block in San Francisco with a really wide sidewalk. It doesn’t slope too steeply toward the street but has a great downhill slope at a moderate pitch. It’s perfect because I can build up some good speed, but not so fast I lose control. Better than most amusement park rides!

Negotiating Curbs and Obstacles

Certain wheelchair features aid in negotiating curbs and other obstacles. Larger, air-filled wheels and casters go over curbs more easily than hard, smaller wheels. Shock absorbers or an independent suspension system also help in getting over changes in surface level. Some power chairs with frontwheel drive are better able to handle a modest curb.

Wheelies?

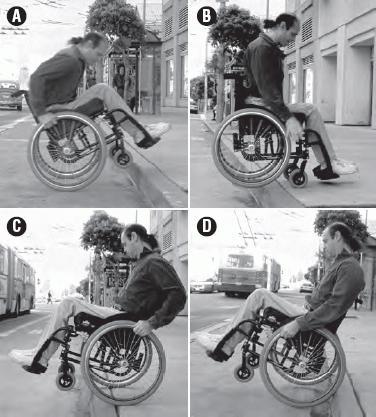

For manual chair riders, riding over obstacles can often be accomplished with wheeling skill, using the wheelie technique—tipping back on the two main wheels. Occupational and physical therapists teach the technique to chair riders who they feel have sufficient strength and balance. The chair will need to be properly adjusted so that the axle is not too far forward—which makes the chair prone to tipping over backward too easily during normal wheeling—or too far backward.

Knowing how to do a wheelie makes it possible to wheel up or down (jump) curbs (Figure 4-12). A highly skilled wheeler can hop curbs several inches high. Some riders can even wheel down a series of steps, assuming each step is wide enough to stop on and allow the riders to check their balance. In some situations, the ability to do wheelies might make the difference between doing it yourself and asking for help, may make it unnecessary for you to have to go out of your way to get to a ramp, and may allow you to independently escape in an emergency.

Figure 4-12 Using the wheelie technique at a curb. Photos A and B show going up a curb; C and D show going down a curb.

Wheelies can help even when there is a ramp or curb cut. When you approach a ramp going upward, a good push at the base just before the incline gives you momentum to get started up the ramp, saving you much energy. If you raise the casters slightly at the same time, you will maintain better momentum. You will not have to overcome the resistance of the casters against the upward-sloping pavement.

If you must wait for a light before crossing the street at a curb cut, don’t go down the curb cut until your way is clear. That way you can use the momentum of going down the curb to help you get back up the crown of the street. Use whatever downhill energy you can, rather than wasting it by stopping at the bottom and having to push uphill with your own power. Doing a slight wheelie as you go down the curb cut will also help you use your momentum to get up the rise in the street. Techniques like this take some practice and, of course, depend on your strength and balance. If you are still working with a physical therapist, you can discuss developing these skills.

Another advantage of the wheelie is that it gives you an opportunity to change your position. Reclining by doing a wheelie changes the pressures on the spine and allows muscles of the upper body to relax, since the back of the chair is now carrying more of your weight. As one chair user notes:

I’m fond of tipping back against a wall and putting my brakes on because I find the change in posture to be a great relief.

Each rider has to find his own limits and account for the dangers of any wheeling technique. Going down stairs alone entails obvious risks. Don’t attempt such methods until you’ve gained confidence through practice with someone to check you against a fall. First, explore your abilities and limits.

Zen Wheeling

Zen Buddhism is a practice in which you bring your full attention into the present moment, instead of reviewing the past or planning the future. Wheeling can be like a Zen meditation exercise. The principle of mindfulness—observing the forces at play right now—can be applied to driving your wheelchair. For instance, riders often encounter very tight spaces. The more patient—or present and observing—you are, the less likely you are to bump into one side or the other, jam a finger, or damage your chair in the process.

Similarly, when you are wheeling along a sidewalk—which is typically sloped toward the street for water drainage—the downhill wheel needs to be pushed a bit harder or the joystick pulled a bit to the side to keep you on a straight line. The more aware you are of the sometimes subtle forces at play on you or your chair, the more accurately you can respond with just the right amount of effort at the right time to keep yourself traveling on a steady path. The better you observe the cracks, potholes, slopes at doorways, metal plates, and various other features of the terrain, the better you can make the fine adjustments in wheeling that they require of you.

When there is a slight rise in a section of concrete, you will want to give a little extra push to raise the front casters very slightly over it, or you will want to slow your power chair just a bit as you approach, then accelerate over it. You can also use your body weight, gently pushing against the back of the chair to slightly lift weight from the casters.

When you are pushing a manual chair up a slope, take your time and feel the forces you are working against. You can waste a lot of effort if you try to go fast, maintain a consistent speed, or always travel in a straight line. If you use your arms fluidly with the shoulders, apply your upper body weight as your balance allows, and note subtle changes in sideways slope, you can find wheeling uphill a calming experience. Sometimes you will even need to allow yourself to slow substantially or stop completely for a moment as you reposition your arms for the next push. The climb will be good exercise, and it will seem that you got up that slope pretty quickly because you stopped worrying how long it was going to take.

When you pay attention and your chair seems like an extension of your body, you will be amazed at the sensitivity to your surroundings you can develop. For example, you will find you are able to judge curb heights or spaces between cars in a parking lot by fractions of an inch.

Other books

Tempting Fate by A N Busch

Undercurrent by Frances Fyfield

Little Amish Matchmaker by Linda Byler

Laceys of Liverpool by Maureen Lee

Vera's Valour by Anne Holman

Emily Windsnap and the Siren's Secret by Liz Kessler

The Hammer of Eden by Ken Follett

The Last Riders - First Four Votes by Jamie Begley

Foxfire (Nine Tails, 1) by Yuki Edo

Close Quarters by Lucy Monroe