Liesl & Po (2 page)

Authors: Lauren Oliver

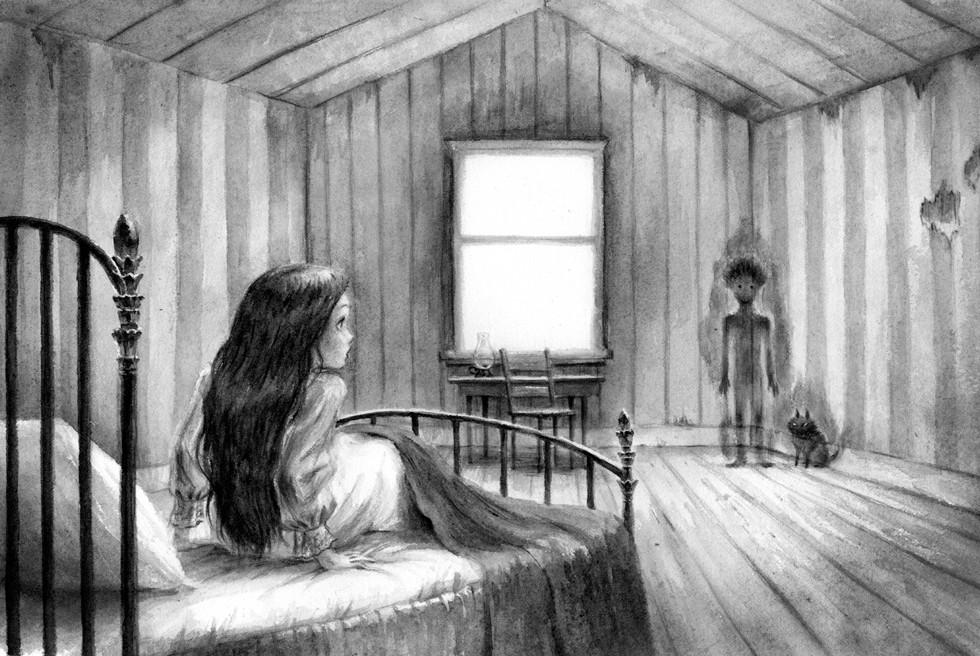

The Other Side was a busy place—as busy, if not busier, than the Living Side. They ran parallel, the two worlds, like two mirrors sitting face-to-face, but normally Po was only dimly aware of the Living Side. It was a swirl of colors to the ghost’s left; a sudden explosion of sounds to its right; a dim impression of warmth and movement.

True, Po could move back and forth between sides, but it rarely chose to. In all the length of its death, Po had only been back once or twice. Why would it go to the Living Side more often? The Other Side was full of wraiths and shadows moving and jostling; and endless streams of dark water to swim in; and vast depths of cloudless night skies to fly in; and black stars that led into other parts of the universe.

“Well, what are you doing in my room, then?” Liesl demanded, folding her arms. She was annoyed that the ghost had called her stupid, and had decided that if Po was going to be difficult, she would be too.

The truth was that Po wasn’t exactly sure why it had appeared in Liesl’s room. (Bundle was there, of course, because Bundle went everywhere Po went.) Over the past few months Po had seen a dim light appear at the edges of its consciousness at the same time every night, and next to that light was a living one, a girl; and in the glow of that light the living girl made drawings. And then for three nights the light had not appeared, nor had the glow, nor had the drawings, and Po had been wondering why when—

pop!

—Po had been ejected from the Other Side like a cork popping out of a bottle.

“Why did you stop drawing?” Po asked.

Liesl had been temporarily distracted from thinking about her father. But now she remembered, and a heavy feeling came over her, and she lay back down in her bed.

“Haven’t felt like it,” she answered.

Po was suddenly at her bedside, just another shadow skating across her room.

“Why?”

Liesl sighed. “My father is dead.”

Po didn’t say anything.

Liesl went on, “He was sick for a very long time. He was in the hospital.”

Po still didn’t say anything. Bundle raised itself up on two hind legs of shadow and seemed to look at Liesl with its moonlight eyes.

Liesl added, “My stepmother wouldn’t let me see him. She told me—she told me he did not want me to see him like that, sick. But I wouldn’t have minded. I just wanted to say good-bye. But I couldn’t, and I didn’t, and now I won’t ever see him again.” Liesl felt a tremendous pressure pushing at the back of her throat, so she squeezed her eyes shut and spelled the word

ineffable

three times in her head, as she always did when she was trying not to cry.

Ineffable

was her favorite word. When Liesl was very small, her father had often liked to sit and read to her: real grown-up books, with real grown-up words. Whenever they encountered a word she did not know, he would explain to her what it meant. Her father was very smart; a scientist, an inventor, and a university professor.

Liesl very clearly remembered one time at the willow tree, when he turned to her and said, “Being here with you makes me ineffably happy, Lee-Lee.” And she had asked what

ineffable

meant, and he had told her.

She liked the word

ineffable

because it meant a feeling so big or vast that it could not be expressed in words.

And yet, because it could not be expressed in words, people had invented a word to express it, and that made Liesl feel hopeful, somehow.

“Why did you want to say good-bye to him?” Po asked at last.

Liesl opened her eyes and stared. “Because—because—that’s what you do when people are going away.”

Po went silent again. Bundle coiled itself around the place Po’s ankles had once been.

“People on the, um, Other Side don’t say good-bye?” Liesl asked incredulously.

Po shook its shadow-head. “They push. They mutter. Sometimes they sing. But they don’t say good-bye.” It seemed to consider this for a second. “They don’t say hello, either.”

“That seems very rude,” Liesl said. “People always say hello to one another

here

. I don’t think I would like the Other Side.”

The ghost in front of her flickered a bit around the shoulders, and Liesl assumed it was shrugging. “It’s not that bad,” Po said.

Suddenly Liesl sat up again excitedly, forgetting all about the tiny nightshirt she was wearing and the fact that Po was a maybe-boy. “My father’s on the Other Side!” she exclaimed. “He must be there, with you! You could take him a message for me.”

Po faded in and out uncertainly. “Not all of the dead come this way.”

Liesl’s heart dropped back into her stomach. “What do you mean?”

“I mean . . .” Po flipped slowly upside down, then righted itself. The ghost often did this when it thought. “That some of them go straight on.”

“On

where

?”

“On. To other places. To Beyond.” When it was irritated, the ghost became easier to see, as its silhouette flared somewhat along the edges. “How should I know?”

“But do you think you could find out?” Liesl sat up on her knees and stared at Po intently. “Please? Could you just—could you just ask?”

“Maybe.” Po did not want to get the girl’s hopes up. The Other Side was vast and filled with ghosts. Even on the Living Side, Po could still feel the Other Side expanding in all directions, had a sense of new people crossing over endlessly into its dark and twisting corridors. And people lost shapes quickly on the Other Side, and memories, too: They became blurry, as Po had said. They became a part of darkness, of the vast spaces between stars. They became like the invisible side of the moon.

But Po knew the girl wouldn’t understand any of this if it tried to explain, so it just said, “Maybe. I can try.”

“Thank you!”

“I said I would try, that’s all. I didn’t say I could.”

“Still, thank you.” Liesl felt hopeful for the first time since her father had died. It had been ever so long since anyone had tried to do anything for her—not since her father had been well, at least, before Augusta had decided that Liesl must move to the attic. And that was months upon months ago: a tower of months, so that when Liesl tried to remember her life before the attic, her memory grew slimmer and slimmer as though it was being stretched, and snapped before it could reach the ground.

Po was next to her. Then it was in the corner again, a person-shaped shadow with a curious shaggy shadow-pet at its feet. Bundle did the mew-bark thing. Liesl decided it sounded like a

mwark

.

“You have to do something for me in return,” Po said.

“Okay,” Liesl said, feeling uneasy. She did not know what she could possibly do for a ghost, especially since she was never allowed to leave the attic. It was, Augusta said, far too dangerous; the world was a terrible place, and would eat her up. “What do you want?”

“A drawing,” Po blurted, and then began to flicker again, this time from embarrassment. It was not used to having outbursts.

Liesl was relieved. “I’ll draw you a train,” she said passionately. She loved trains—the sound of them, at least. She heard their great horns blasting and the rattle of their wheels on the track and listened to them wailing farther and farther away, like birds calling to one another in the distance, and sometimes she confused the two sounds and imagined the train had wings that might carry its passengers up into the sky.

Po did not say anything. It seemed to pour itself into the regular corner shadows. All at once it blended in with Bundle’s shadow, and then with the shadow of the crooked desk, and three-legged stool.

Liesl sighed. She was alone again.

Then Po’s silhouette pulled itself abruptly away from the corner. It looked at Liesl for a moment.

“Good-bye,” Po said finally. Bundle went,

Mwark

.

“Good-bye,” Liesl said, but that time Po and Bundle were gone for real.

AT THE VERY MOMENT THAT LIESL WAS SPEAKING

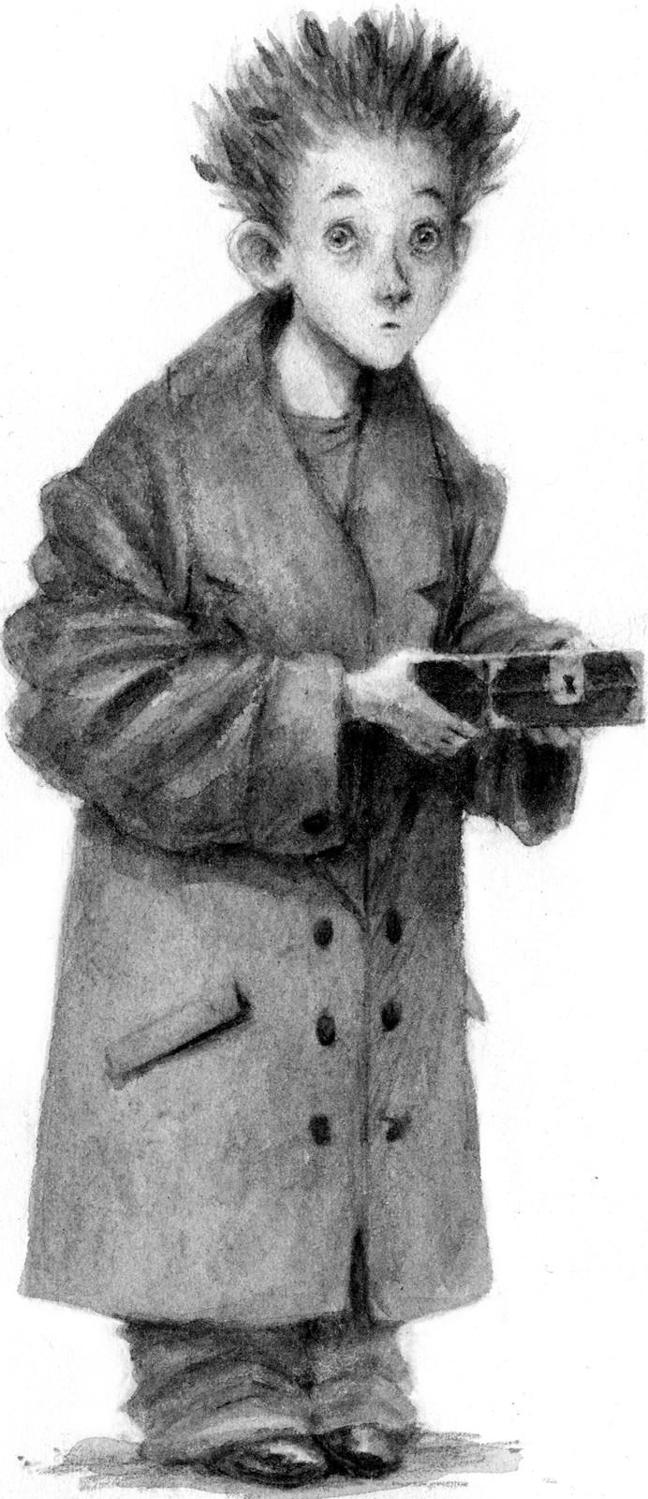

the word “Good-bye” into an empty room, a very frazzled-looking alchemist’s apprentice was standing on the quiet street in front of her house, staring up at her darkened window and feeling sorry for himself.

He was wearing a large and lumpy coat that came well past his knees and had, in fact, most recently belonged to someone twice his age and size. He carried a wooden box—about the size of a loaf of bread—under one arm, and his hair was sticking up from his head at various odd angles and had in it the remnants of hay and dried leaves, because the night before he had once again messed up a potion and been forced by the alchemist to sleep out back, where the chickens and animals were.

But that wasn’t why the boy, whose name was Will but who also answered to “Useless” and “Hopeless” and “Snot-Face” and “Sniveler” (at least when the alchemist was the one calling to him), felt sorry for himself.

He felt sorry for himself because for the third night in a row the pretty girl with the straight brown hair was not sitting in the small attic window, framed by the soft golden glow of the oil lamp to her left, with her eyes turned downward as though she was working on something.

“Scrat,” Will said, which was what the alchemist usually said when he was upset about something. Because Will was extremely upset, he repeated it. “Scrat.”

He had been sure—sure!—that she would be there tonight. That was why he had come so far out of his way; that was why he had looped all the way around to Highland Avenue instead of going directly to Ebury Street, as the alchemist had told him a dozen times he must do.

As he had walked down empty street after empty street, past row after row of darkened houses, in silence so thick it was like a syrup that dragged his footsteps away into echoes before he had placed a heel on the ground, he had imagined it perfectly: how he would come around the corner and see that tiny square of light so many stories above him, and see her face floating there like a single star. She was not, Will had decided long ago, the type of person who would call him names other than his own; she was not impatient or mean or angry or snobby.

She was perfect.

Of course, Will had never actually spoken to the girl. And some small corner of his mind told him it was stupid to continue finding excuses, every single night, to go past her window. It was a waste of time. It was, as the alchemist would have said,

useless

. (

Useless

was one of the alchemist’s favorite words, and he used it interchangeably to describe Will’s plans, thoughts, work, appearance, and general selfhood.)

Will was sure that if he ever had the chance to speak to the girl in the window, he would be too afraid to. Besides, he felt certain he would never have that chance. She stayed in her window, far above him; he stayed on the street, far below her. And that was how things were.

But every night for the past year since he had first seen her heart-shaped face floating there in the middle of that light, and no matter how many times he had scolded himself or tried to go in the opposite direction or sworn that he would stay away from Highland Avenue

no matter what

, his feet had seemed to circle him back toward that same stretch of sidewalk just below her window.