Liesl & Po (9 page)

Authors: Lauren Oliver

People could push and pull at you, and poke you, and probe as deep as they could go. They could even tear you apart, bit by bit. But at the heart and root and soul of you, something would remain untouched.

Po had not known all this when he was alive, but the ghost knew it now.

“He said that he should never have eaten the soup,” Po said, and waited to see whether this would mean anything to Liesl.

She scrunched her mouth all the way to her nose. “The soup? What soup?”

“I don’t know. That’s what he said, though.”

“Did he say anything else?” Liesl asked impatiently. It was annoying that Po had crossed into the land of the dead, and back, only to deliver a message about an unsatis-factory meal.

“Yes.” Po hesitated. “He said that he must go home. He must go back to the place of the willow tree. He said that he will be able to rest then. He said you would bring him there.”

Liesl sat very still. For a moment she was so still and white Po was actually frightened, though he had never once been frightened of a living one before. They were too fragile, too easily broken and dismantled: They had bones that broke and skin that tore and hearts that gave up with a sigh and rolled over.

But that was the problem with Liesl, Po realized. She seemed in that moment, as she sat there with her thin blanket bunched around her waist, to be like a glass thing on the verge of breaking. And the ghost did not

want

her to break.

Bundle must have felt it too. Po saw the fuzzy animal shape grow fuzzier and then sharper, fuzzier and then sharper, as it tried unsuccessfully to merge with Liesl. This was the other problem with living ones: They were separate, always separate. They could not truly merge. They did not know how to be anyone other than themselves, and even that they did not know how to be sometimes.

“I must take his ashes to the willow tree,” Liesl whispered suddenly, with certainty. “I must bury my father next to my mother. Then his soul will move Beyond.” She looked directly at the place where Po’s eyes should have been, if Po were not a ghost, and again Po felt the very core of its Essence shiver in response.

“And you must help me,” Liesl finished.

Po was unprepared for this. “Me?” it said unhappily. “Why me?”

“Because you are my friend,” Liesl said.

“Friend,” Po repeated. The word was unfamiliar by this point. Something tugged at the edges of Po’s memory, the faintest of faintest recollections of a bark of laughter, and the smell of thick wool, and the sting of something wet against its cheek.

Snowball fight

, Po thought suddenly, without knowing where the words came from: words he had not thought of in ages and ages, in so long that millions of stars had collapsed and been born in that time.

“All right,” Po said. It had never occurred to Po that it would ever have a friend again, in all of eternity. “I’ll help you.”

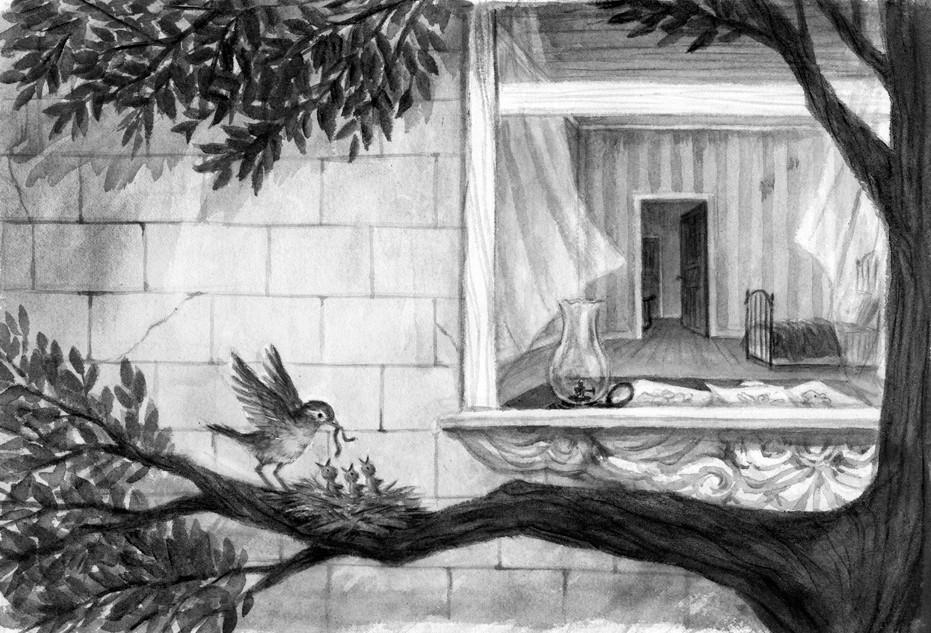

“I knew you would!” Liesl went to throw her arms around the ghost and nearly toppled over, as her arms passed through nothingness and then back on herself. Then, all at once, she seemed to collapse from within. She slumped back against the pillows. “But it’s no use,” she said despairingly. “How am I supposed to bury my father by the willow? I’m not allowed to leave the attic. I haven’t left the attic in months and months. Augusta says it’s too dangerous. I must be kept here, for my own protection. And the door is locked from the outside. It’s only ever opened twice a day, when Karen comes to bring me my tray.”

Karen was one of the servants Augusta, Liesl’s stepmother, had hired with Liesl’s father’s money. Karen trundled up the winding stairs twice a day, sometimes with as little as a tiny strip of the smallest, toughest meat—usually the scraps from Augusta’s meal—and a thimbleful of milk.

Augusta had not seen Liesl herself in all thirteen months that Liesl had been in the attic, and although Augusta had three servants and had her hair done every other day, she was always complaining that Liesl ate too much and they couldn’t possibly afford to feed the little Attic Rat any more than they were already giving her.

Po was silent for a bit. “What time does she bring up your tray?” the ghost finally asked.

“Before dawn,” Liesl said. “I’m usually asleep when she comes.”

“Leave everything to me,” Po said, and Liesl knew then that picking Po to be her very best friend had been the right thing to do.

KAREN MCLAUGHLIN DID NOT LIKE TO GO TO THE

attic. She disliked climbing three staircases, and then another set of tiny wooden stairs, to get from the kitchen to the door, particularly when she had to carry a tray with her. But more than that, she disliked seeing Liesl. It gave her a shivery feeling—the girl with her pale, pale face and enormous blue eyes, the girl who never cried or shouted or made a fuss about being locked in the attic but only sat there, staring, when Karen came in. It gave Karen the creeps. It was just

not right

.

Even Milly, the cook, said so. “It ain’t natural,” she liked to say, as she poured a bit of hot water over a bouillon cube for Liesl’s soup, or pounded a piece of fat and gristle with a large hammer so Liesl would at least be able to get her teeth through it. “Little girls ain’t made to be locked up in attics like bats in the belfry. It’ll bring bad luck on us all, you wait and see.”

Milly was always saying, too, that

something should be done

, though her declarations never went further than that. Times were hard, jobs were few, and people all over the city were starving. If the servants in Augusta Morbower’s employ had to deal with the specter of a pale, small child who lived in the attic—well, there were worse things.

(That was the kind of world they lived in: When people were afraid, they did not always do what they knew to be right. They turned away. They closed their eyes. They said,

Tomorrow.

Tomorrow, perhaps, I’ll do something about it.

And they said that until they died.)

Privately, Karen suspected that Liesl was a ghost, as she was very superstitious. Everyone was superstitious in those times of grayness and dark, when the sun had long ago stopped shining, and the color had slowly drained from the world.

True, Karen did not know of any ghosts who ate, and Liesl was always cleaning her plate of whatever food was placed there, no matter how disgusting or half-rotten. And true, too, that on the few occasions when Karen had been forced to touch the girl (twice when she had caught a fever; once when some of the fish Milly had sent up had been spoiled, and the girl had been ragingly sick for a whole day), Liesl had felt solid enough. But all in all, seeing Liesl gave Karen an uncomfortable, prickly feeling she could not quite identify: a feeling that reminded her of the time she had been caught by the nuns at her school stealing a chocolate chip cookie from Valerie Kimble’s lunch basket—a feeling of being watched, and judged.

That was why she so dreaded her twice-daily trips up the narrow attic stairs, and why, as much as possible, she tried to come only when she knew the girl would be sleeping.

It was just after five thirty in the morning when she began making her way carefully up the stairs, balancing the tray, which today contained a bit of bread mixed with hot water to form a pasty porridge, and the usual few sips of milk. The house was even quieter than usual, and the shadows seemed to Karen particularly strange and black and huge. Suddenly she felt something brush her ankle and she jumped, nearly dropping the tray; a cat meowed in the darkness and she heard the scrabbling of paws on the wood, moving past her down the stairs. She exhaled. It was only Tuna, the mangy cat who had been informally adopted by the kitchen staff and who occasionally roamed the house at night, when Augusta wasn’t around to give him a swift kick in the belly.

“Nothing but a kitty,” Karen muttered to herself. “A little bitty kitty.” But her heart was hammering, and she felt sweat pricking up under her arms. Something was wrong in the house this morning. She felt it; she

knew

it.

It was the ashes, she realized: that pile of ashes sitting in the wooden box on the mantel. It wasn’t right; it wasn’t

natural

. Like having a dead person propped up in the living room. And didn’t ghosts always hover around their bodies? Even now, the master of the house could be watching her, tiptoeing up the stairs, ready to wrap his dark and ghostly fingers around her exposed neck. . . .

Something brushed against her cheek, and she cried out. But it was just a draft, just a draft.

“No such thing as ghosts,” she whispered out loud. “No such thing as ghosts.”

But it was with a feeling of dread and terror that she climbed the last three steps to the attic and carefully unlocked the door with the large skeleton key she kept in her apron pocket.

Several things happened quickly, one right after the other.

Liesl, who was sitting up in bed, not lying down with her eyes closed as she should have been, said, “Hello.”

Po, standing directly next to her in the darkness, concentrated with all its might on distant memories of something vast and white burning high up in the sky, and its outline began to glow like a star peeking out against the darkness: faintly at first, then clearer and clearer, the outline of a child whose body was all made of blackness and air.

Po said, “Boo.”

Bundle went,

Grrr

.

Then:

Karen dropped her tray.

Karen cried, “God help us!”

Karen turned and went running down the attic stairs as quickly as she could, a little noise of utter terror bubbling from her throat.

And:

In her haste, Karen forgot to lock the door behind her.

“Quickly,” Po said to Liesl. Liesl flung away her covers and stood up. She was not dressed in her thin nightshirt, but in trousers, a large, moth-eaten sweater, an old purple velvet jacket, and regular shoes. She had not worn anything but slippers in so long, she had difficulty walking at first.

“We don’t have much time,” Po said, skating silently in front of her. The effort of appearing to the servant girl had been tiring, and Po allowed itself to ebb back to its normal shadowed state. “Hurry, hurry.” Bundle zipped back and forth, materializing in various corners, and then briefly on the ceiling, in its excitement.

“I’m hurrying,” Liesl whispered back. She slung the small sack she had packed earlier—containing a change of clothes, her drawing supplies, and a few odds and ends from the attic—over her shoulder, and moved carefully to the door. A feeling of fear and wonder swept over her. It had been ever so long since she’d been out of the attic. She was almost afraid to leave it behind. She could no longer remember clearly what was on the other side of the door; what it felt like to stand outside, in the open air. She did not know how she would manage with no money and no clear idea of where she was going, and for a moment she thought of saying to Po,

I’ve changed my mind

.

But then she thought of her father, and the willow tree, and the soft moss that grew over her mother’s grave, and instead she said, “Good-bye, attic,” and followed the ghost’s dark shape out of the door and down the stairs.

And while Karen was babbling to Milly in the kitchen, and Milly was fussing and murmuring, “Calm down, calm down, I can’t understand a word of what you’re saying” and wondering, privately, why every single servant had to be either a drunk or completely off her rocker, a little girl and her ghostly friend and a small ghostly animal were taking from the mantel in the living room a wooden box containing the most powerful magic in the world, and afterward stealing with it out into the street.