Let's Ride (5 page)

Authors: Sonny Barger

With maybe the exception of the Italian motorcycles, which still seem to have lots of electrical problems, most bikes sold today have reliable electrical systems and this shouldn’t be something you have to worry about unless you hook up too many electrical accessories like heated seats, grips, vests, or driving lights. You will have to keep your battery charged, but this isn’t that hard to do. If you ride every day, your battery should last for years. Even if your bike sits for weeks at a time, you can hook up a trickle charger that will keep your battery charged while waiting for you to go for a ride.

TRANSMISSIONS

M

ODERN TRANSMISSIONS ARE ANOTHER

part of the motorcycle that don’t warrant a lot of owner attention. With the exception of some Yamaha models, most modern motorcycle transmissions are as reliable as most automotive transmissions (I’ll discuss Yamaha’s past transmission problems in the section on buying used motorcycles).

Most motorcycles use six-speed or five-speed manual transmissions. A few bikes use automatic transmissions, but these are still controversial and haven’t been widely accepted. The odds are one thousand to one that you’ll end up with a manually shifted motorcycle with a hand-operated clutch and a foot-operated shifter. If you’re used to automatic transmissions in your car, don’t worry—shifting a motorcycle is a lot easier than it sounds. I’ll discuss that in the section on operating your motorcycle.

SADDLES

O

THER THAN THE ENGINE,

which dictates the character of a motorcycle, the system that will most affect you as a rider will be the controls and accommodations. When you start riding, you might not realize what kinds of seats, seating positions, and control arrangements best suit your body because you’ll be so focused on mastering your riding skills that you won’t give comfort much thought. As your riding skills develop, however, and you start to put longer and longer days in the saddle, comfort will become a much higher priority. Nothing takes the fun out of a long day of riding like an uncomfortable seat.

You might guess that the saddle is the single most important factor in being comfortable, and in a way it is—if your butt is burning, the rest of you is going to be damned uncomfortable, too. Most stock saddles are garbage, designed to provide the lowest possible manufacturing cost rather than maximum comfort. There are quality aftermarket saddles available from a variety of sources that will keep you comfortable for many hours after the stock saddle has given up all hope of supporting your ass. In my experience, Corbin makes the best seat available—I’ve ridden on them for almost twenty years.

WIND PROTECTION

T

HE SADDLE IS THE

most obvious item that contributes to your comfort on a bike, but wind protection plays a big part, too. A lot of people like riding on motorcycles without fairings (the plastic bodywork that protects the rider from the wind) or windshields, and you might, too, but I like to have some wind protection. I switched to touring bikes with full weather protection in 1983. I had to start using fairings at that time because I had throat cancer and after a laryngectomy (surgery that left me breathing through a hole in my neck) the wind shear made it impossible for me to breathe, but I’m glad I switched to touring bikes. I feel a lot less tired after a long day in the saddle when I’ve been on a bike with a windshield or fairing.

I prefer a tall windshield, but some people don’t like having to look through them. People who wear full-face helmets sometimes don’t mind the wind flowing past their heads, as long as it doesn’t knock their heads around. They consider a well-designed windshield or a fairing one they can look over, and not through, one that directs a clean, nonturbulent flow of air over and around their helmets. Klock Werks makes a windshield called the Flare for Harley baggers (touring motorcycles with saddlebags) that does a great job of smoothing out the airflow.

RIDING POSITION

W

HEN YOU START RIDING,

you’ll probably be more concerned with how you look on your bike than how you feel on it. I don’t really give two shits about how you look on your bike. Ape hangers (a tall handlebar that makes you reach for the sky to put your hands on the controls) might look cool, but they put a lot of pressure on your lower back and turn you into a giant sail to catch the wind.

The same goes for forward-mounted foot controls; you may look cool as ice leaned back in your saddle, your feet kicked way out in front of you like you were sitting in your La-Z-Boy recliner, but you’ll be using your lower back to fight the wind the entire time you’re on the road.

The sad fact is that most of us aren’t that pretty to start with. I know I’m not. The way I see it, most of us are never going to look like movie stars on our bikes, no matter how uncomfortable we make ourselves; we might as well be comfortable.

Motorcycles are a lot more complex than they might seem at first glance, but you really need to keep only the following few things in mind.

W

HAT

Y

OU

S

HOULD

K

NOW

- The engine gives the motorcycle its character.

- Horsepower might win races, but on the street torque is king.

- The more comfortable your bike, the more you enjoy riding.

© by Sonny Barger Productions

Types of Bikes

What to Ride

M

y goal is to make you a lifelong motorcyclist. You’ll need to do a lot more than just buy a $20,000 Harley—you’ll need to devote yourself to not only learning to ride, but also learning to appreciate the ride. You’ll know you’ve become a serious motorcyclist when you don’t ride just because your buddies are taking their bikes out together; you ride because you can’t wait to feel the freedom of the open road. Hell, you won’t ride because you want to ride; you’ll ride because you

need

to ride.

To get to that point, you need to rack up many miles in the saddle, and having a comfortable motorcycle makes putting in those hours a lot more fun. This is something you should keep in mind from the very beginning, when you first start thinking about getting a motorcycle. There’s a lot more to being comfortable on your bike than just saddles, handlebars, and windshields. The type of bike you choose will go a long way to determining how at ease you become on your bike.

If you’re just starting out, it’s easy to be confused by all the different kinds of motorcycles on the market. And even if you’ve been riding awhile, you may have picked a bike that’s not the right bike for you, and now you’re stuck with a machine that doesn’t meet your needs.

When it comes to picking a bike, in the end it boils down to what you like. You need guts to ride the bikes you like the best. You should decide what’s important to you and then pick the best bike that meets your requirements. Don’t choose a motorcycle to impress other people; choose one that impresses you.

Don’t worry about what other people think.

Instead, decide what bike’s best for you, then get out there and have fun on it.

I pick my bikes based on my own priorities. As I’ve mentioned, it’s important to me to ride an American bike. I have always ridden American, which is why I stuck with Harley-Davidson until Victory’s bikes came along. I feel that way about everything. I ride an American-bred quarter horse, and I drive an American pickup (a Chevy). I grew up during World War II and was taught to buy

only

American.

It hasn’t always been easy to ride American. I’ve never liked Harleys much—I’ve always considered them to be the bottom of the technology pile—but I rode Harleys for fifty-two years because they were the best American bikes. Today I ride a Victory Vision because I think that’s the finest bike America makes. There are so many good motorcycles to pick from today that it’s hard to judge them all, but I’ve ridden enough to know that my Victory stacks up well against any of them.

In this section I’m going to help you figure out what’s important to you when it comes to your bike. We’re going to look at the types of motorcycles out there and examine the advantages and the disadvantages of each. We’re going to talk about the comfort, controllability, reliability, and convenience of each type of bike.

Once you understand all of this, you might find that the bike you intially thought you wanted is actually the wrong bike for you. You may think you want a big bagger but you might not be aware of the challenges of riding a bike that’s physically too large for you to ride smoothly and controllably. And you might not be aware of the costs associated with a bagger. For instance, it’ll cost you more to mount new tires on an Electra Glide or Gold Wing than you’ll spend on maintenance in an entire year for a Sportster. And it costs a lot more to change tires on a crotch rocket than on a dual-sport machine. Once you know what types of motorcycles are out there, you’ll be better able to understand the costs associated with each.

When I first started riding, there wasn’t much variety from which to choose. One bike more or less served every purpose. You could buy a single-cylinder British bike like a BSA Gold Star and do everything with it, from commuting to racing. If you wanted to ride it off-road, you took off the lights and fenders and put on a set of dirt tires. With that setup, you could use it for trail riding, dirt-track racing, or hare scrambles, which are cross-country races. If you wanted to road race it, you could get a racing fairing, mount a set of road tires, and presto! You had a competitive road racer. And if you wanted to travel across the country, you just threw on a set of saddlebags and were set to hit the road. Beginning in the 1960s, motorcycles began to get more specialized. This trend has continued to the point that today many motorcycles are so narrowly focused they’re only really good for doing one thing.

ON-ROAD VERSUS OFF-ROAD

P

ROBABLY THE MOST BASIC

division between types of motorcycles is on-road versus off-road. I picked those categories instead of “dirt” versus “street” because by “off-road” I mean any motorcycle you can’t license for use on public highways; this includes all racing motorcycles, whether those motorcycles are meant for racing on dirt or pavement. This book is a street-survival guide, and we’re going to focus on motorcycles you can legally ride on the street.

Racing motorcycles, whether dirt bikes or road racers, are the most highly specialized motorcycles of all, and riding them requires specialized training and skills. Lots of good books and training schools are available for anyone interested in racing motorcycles, so we’re not going to get into that here. We’ll discuss riding on gravel and dirt roads when we get to riding techniques, and even talk about some mild trail riding, but it will be the type of riding you might be able to do on a street bike or a street-legal dual-purpose motorcycle.

The requirements for licensing a motorcycle to legally ride on the street vary from state to state, but the minimum requirements for a motorcycle to be street legal are usually that it has a functioning headlight, a taillight, a brake light, and often a horn. Most states also require turn signals on newer models.

That doesn’t mean you can just take a race bike or a dirt bike, wire up some lights, and go get a license plate. Likewise you might run into problems if you try to license a custom-built motorcycle, or if you’ve bought a custom-built motorcycle from a builder. Almost every state requires a motorcycle to be manufactured specifically for use on public roads, meaning that it will pass all state and federal department of transportation and emissions requirements. Usually the licensing bureau can tell if your bike is legal just from the serial number.

Some people have figured out how to get license plates on just about anything, but I’ve never had any reason to do this. I always ride street-legal motorcycles, so I’ve never looked into what’s involved. Besides, licensing a nonconforming motorcycle is illegal just about everywhere, and in some states doing so will even land you in jail.

I’ve got people from various law-enforcement agencies watching my every move so I can’t get away with anything. The last thing I need is to end up in jail because I broke the law to get a license plate for a Harley XR750 dirt-tracker or some one-off chopper that doesn’t meet state and federal regulations. The feds would probably say it was a larger conspiracy and charge me with racketeering. If you want to do this, that’s your business, but you’ll need to seek advice from someone else.

ANTIQUE MOTORCYCLES

Y

OU’LL ALSO HAVE TO

learn about antique motorcycles elsewhere. This book is a guide for people who want to become hard-core motorcyclists, riders who want to get out on the road and put some serious miles under their butts. For that you’re going to need a reliable modern motorcycle that doesn’t break down or need extraordinary maintenance. That rules out antique or custom motorcycles.

Antique motorcycles have old parts that are often worn out and hard (or even impossible) to replace when they break out on the road. They just don’t make this stuff anymore. This was true even before these bikes became antiques; back in the 1950s when we rode motorcycles built in the 1940s, it was nearly impossible to find replacement parts. Even if the antique motorcycle has been perfectly restored, you’ll still be relying on an outdated electrical system. Most antique engines either use undependable six-volt systems or they have total-loss magneto systems, neither of which is conducive to having a motorcycle that starts every time you need it to start.

There is something kind of cool about kick-starting an old motorcycle. It requires skill to get an old bike running, but take it from me—it’s a lot of work. Having a motorcycle that starts every time you push a button on your handlebar is very convenient. If a bike has a kick-starter, it’s almost certainly an antique and is best suited for sitting in someone’s collection, and not for getting you where you need to go.

Old bikes might be cool, but everything about modern motorcycles is better than old bikes, from a practical standpoint. Even the basic material from which manufacturers make engines has improved over time. Now engines are made out of aluminum instead of cast iron because aluminum cools better and thus doesn’t wear out as fast.

Still, antique motorcycles are great to look at in shows. It’s fun to see how motorcycle technology developed, and for some of us old-timers it’s nostalgic to see the types of bikes we used to ride. But when it comes to getting from one place to the other safely and reliably, I wouldn’t want to go back to the old days. Give me the most functional, reliable modern motorcycle available. Unless you are a wizard mechanic who can overhaul your bike by the side of the road with nothing but an adjustable wrench and a Zippo lighter, you’re better off avoiding “classic” bikes as your main source of transportation.

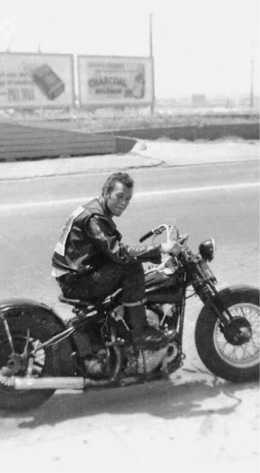

CHOPPERS AND BOBBERS

I

ALSO RECOMMEND STAYING

away from custom motorcycles when you’re starting out, for the same reason you should avoid antiques: they are complete pains in the ass to own and ride. Custom motorcycles are bikes that have been modified or even built from scratch. The most common are choppers and bobbers.

When I first started riding, if you said the word

motorcycle

in the United States, the first thing that came to mind was a big, heavy Harley-Davidson. At the time these were the best bikes available for comfortable highway riding, but a lot of us wanted more performance than a stock Harley was capable of delivering. We didn’t have much money to buy parts to make the engines faster, and even if we did, such parts weren’t easy to come by. We couldn’t just go online, order whatever we wanted, and have it shipped across the country. More often than not if we wanted a specific part, we had to figure out a way to make it ourselves.

A cheaper and easier way to make our bikes faster was to take parts off and make them lighter. That didn’t cost any money at all, so most of us younger guys chopped parts off to create stripped-down hot-rod bikes. We’d take off fenders, extra lights, any bodywork that wasn’t absolutely necessary, and pretty much anything else that didn’t contribute to making the bike faster. Some guys even took off the brakes!

We never really had a name for the bikes we customized. According to the stories you read in the press, people called this type of bike a “bobber” or a “bob job,” because some people called taking off parts “bobbing” back then. They’re still called “bobbers” today, but I think names like “bobber” and “chopper” came from the motorcycle industry and not the people out there customizing bikes. They probably figured it would be easier to sell us junk if they gave it a catchy name.

By the time the industry types started calling our custom bikes “choppers,” we’d begun to focus more on style. This happened during a wild time in our country’s history. A lot of craziness was happening, and we were young and a little wild ourselves. Our bikes reflected that. People started chopping and rewelding frames to increase the rake of the bike (the angle at which the fork extends away from the frame). They also made forks longer and handlebars higher. Every year people made their forks longer, their handlebars higher, and their rakes more extreme until it got so out of control that the bikes became just about impossible to ride.

Throughout all this insanity I kept my bikes pretty functional. I did some stuff that I now realize was probably crazy, like removing the front brakes and extending the front forks, though never by more than four inches. I also took the rocker-arm clutch pedal and cut it in half, turned it upside down, and made a suicide clutch out of it. With no front brake and a suicide clutch, I had to hit neutral at every stop. That’s not the safest way to stop.

I never changed the rake on any of my bikes; a radically raked front end is one of the main characteristics of a chopper. Then, as now, I liked to ride more than anything. I like to move hard and fast, which is not what choppers are meant to do. Engineers spend years developing the best angle for a bike’s rake, which largely determines how a bike handles. In the 1940s Harley tried a different rake on its bike each year, looking for the perfect angle, but the company never quite nailed it because the Harleys of the 1940s and even 1950s needed steering dampers to prevent high-speed wobbles. I don’t think Harley really got it right until the 1960s, when it was able to do away with the steering damper.

If it took Harley decades to find the perfect angle for the rake of its bikes, I don’t expect that I’d be able to improve a bike much by spending an afternoon cutting and welding my frame to get a different rake. I’m not an engineer, but neither are all the other people experimenting with the rakes on their custom bikes. As a result of all this backyard engineering, virtually every radically raked custom bike built during the 1960s and 1970s was unsafe to ride.

I’ve talked to custom bike builders today who claim that they’ve figured out the right measurements to make a radically raked custom bike safe to ride, and I imagine that they’re a lot safer than earlier examples, but I have a hard time believing that these builders can make a bike handle as well as the engineers who design frames using decades of research on motorcycle handling.

Arlen Ness, the king of the customs, may be an exception. Arlen has been a very good friend of mine for over fifty years and probably knows as much about engineering a motorcycle chassis as anyone at any motorcycle-manufacturing company. His bikes handle better than any other custom I’ve ever ridden (and better than a lot of factory bikes), but I still ride a mostly stock motorcycle. When it comes to motorcycle riding, I have enough to worry about without having a bike that is trying to kill me because of its poorly engineered chassis. I want my motorcycle to be safe; just “safer” doesn’t quite cut it.