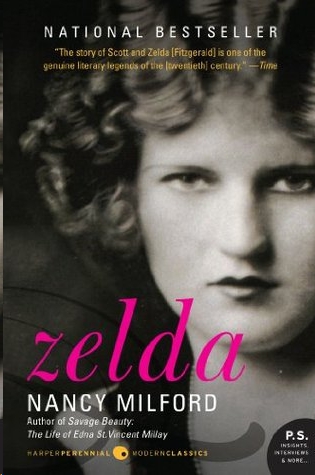

Zelda

Authors: Nancy Milford

ZELDA

A Biography

Nancy Milford

For Kenneth,

with love and thanks.

For Matthew and Jessica Kate

Contents

Biography is the falsest of the arts.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD,

General notes to

The Last Tycoon

W

HEN I WAS YOUNG IN THE MIDWEST

and had dreams of my own, it seemed to me a fine thing to live as the Fitzgeralds had, where every gesture had a special flair that marked it as one’s own. Together they personified the immense lure of the East, of young fame, of dissolution and early death—their sepia-tinted photographs in rotogravure sections across the country: Scott, in an immaculate Norfolk jacket, gesturing nervously with a cigarette, Zelda brightly at his side, her clean wild hair brushed back from her face. But it was not her beauty that was arresting. It was her style, a sort of insolence toward life, her total lack of caution, her fearless and abundant pride. If the Fitzgeralds were ghostly figures out of an era that was gone, they had nevertheless made an impact on the American imagination that reverberated into my own generation. I wanted to know why.

In the spring of 1963, when I had just turned twenty-five, I began to gather reminiscences from people who had known the

Fitzgeralds well, people who had shared a summer house, or a childhood. I remember Gerald Murphy turning to me once and saying suddenly, “Zelda was an American value!” He said it almost in fury, as if she had eluded him until that very moment. For she was an elusive woman. She was also vulnerable and willful and in deep hiding. Sara Murphy caught something of it in her letter to Scott written after Zelda’s first breakdown, “I think of her face so often, & so wish it had been

drawn.

… It is rather like a young Indian’s face, except for the smouldering eyes. At night, I remember, if she was excited, they turned black—& impenetrable—but always full of impatience—at

something

, the world I think. She wasn’t of it anyhow …. She had an inward life & feelings that I don’t suppose anyone ever touched—not even you—She probably thought terribly dangerous secret thoughts….”

What was Zelda to Scott that she haunted his fiction? What was it like to come to New York City in the spring of 1920, fresh out of Alabama, before your twentieth birthday? And marry Scott Fitzgerald, who was going to name the new decade the Jazz Age and make you the first American Flapper? I remember talking to two old men in Montgomery, Alabama, at the fiftieth reunion of Zelda’s high-school graduation, about the time she had ridden down Dexter Avenue in the center of town in a one-piece flesh-colored knit bathing suit with her legs draped nonchalantly over the back of the rumble seat of somebody’s electric. A group of boys, who were called Jelly Beans, hollered at her as she went by, and, seeing them, she stood up in the car, laughing, stretched out her arms wide and called,

“All my Jellies!”

One of the men said, “You see, you’ve got to remember, to us Zelda was a… a Kingmaker.”

Was it Zelda, then, shooting craps like Nancy Lamar in “The Jelly Bean,” tippling with the boys at Princeton and later at the Ritz Bar in Paris? How curious that the same woman who kissed men on fire escapes because she liked the shapes of their noses or the cut of their dinner jackets would also spend hours drawing Scott pictures of Gatsby, drawing him again and again until her fingers ached and until Scott could see him. Certainly we knew more about Gloria and Sally Carrol and Nicole Diver than we did about Zelda Fitzgerald.

In the summer of 1963 my husband and I traveled more than a thousand miles from New York to Baltimore and Washington, into the

Smoky Mountains to Asheville, and then down deeper through the heat and pines of Georgia to Montgomery, Alabama, in search of Zelda. It was on that first trip into the Deep South that, piecemeal, I began to read the documents that are the backbone of this book. The hundreds of letters, the albums of clippings, scrapbooks, the dark-red Moroccan leather book with its wonderful array of addresses—from “Charlie McA’s bootlegger” in Manhattan and “trick corsets” on the rue d’Alger in Paris to the peripatetic “Ernest Hemminway, 113 Rue Notre Dame des Champs,” “Ernest Hemminway, Hotel Taube, Schruns, Vorarlberg, Austria,” until she finally corrects the spelling of his name and settles his address firmly: “c/o Guaranty Trust Co.”

Sitting up late at night in Henderson, North Carolina, in a small tourist home reading Zelda’s letters to her husband moved me in a way I had never been moved before, touched something in me that before those letters had been untouched. We were not pursuing a nostalgic past, nor did the Fitzgeralds represent it to us. Rather we read those letters out loud to each other as if they had just arrived, not knowing from what terrain of their lives they had been written or what the next one would say. They were hopelessly mixed up and undated, without, in most cases, envelopes to give them dates. AH the clues were internal, and were to be pieced together on other days and nights during the ensuing years. A note from Gertrude Stein would fall out thanking the Fitzgeralds for their visit—but what visit, and where? A snapshot taken in North Africa of Scott and Zelda riding camels might come next or a gold lock of Zelda’s hair tied in a pink ribbon. I had somewhat innocently—if a passionate curiosity about another’s life is ever innocent—entered into something I neither could nor would put down for six years, and in that quest the direction of my life was changed. Ahead of me were encounters in this country, in London, Paris, and Switzerland I could never have dreamed of, never invented.

In Montgomery, at the end of her life, disfigured by years of fighting against a recurring mental illness, Zelda would often walk out to a large ante-bellum home when the sun was strong. She had been invited to paint in the gardens whenever she liked. It was a spacious house, encircled by a fine white portico and by lush and fragrant growths of flowers. There was a cutting garden, a formal garden, and a rambling one carefully cultivated to appear wild. In the summertime

the grand pieces of richly carved dark furniture were draped in white cloth, and wooden-bladed fans gently stirred the heavy air. There, in the gardens by the house, Zelda would put up her easel and paint until the sun went down. The bold southern flowers now fascinated her more than the subtle violet or the complex rose; she liked the waxy, almost artificial-looking tropical flowers, the calla lily and the large blossoms of the japonica. Once Zelda asked the lady whose gardens they were, what a

datura

meant to her. The puzzled woman replied, “Well, it’s just a pretty flower, that’s all.” Zelda said nothing and continued to paint. The

datura

is also known as Angel’s Trumpet because of its shapely long white flaring blossom. It is not only beautiful but highly poisonous. Years later, sitting on the portico of that house as the summer light grew dim, the woman leaned toward me and asked quietly, “Where was she that she could not come back? Where did she go? Where?”

Writing about Montgomery, but calling it Jeffersonville, Zelda had said, “Every place has its hours.… So in Jeffersonville there existed then, and I suppose now, a time and quality that appertains to nowhere else.” The time is of our past. The landscape is by Rousseau and something savage lurks in the extravagantly green gardens. Zelda would come full circle to her origin. She was the American girl living the American dream, and she became mad within it.

New York City

N

ANCY

M

ILFORD

February, 1970

Of Lovers ruine some sad Tragedie:

I am not I, pitie the tale of me.

S

IR

P

HILIP

S

IDNEY

,

Astrophel and Stella

, 45

I

F THERE WAS A CONFEDERATE ES

tablishment in the Deep South, Zelda Sayre came from the heart of it. Willis B. Machen, Zelda’s maternal grandfather, was an energetic entrepreneur tough enough to endure several careers and robust enough to outlive two of his three wives. He came to Kentucky from South Carolina as a boy when the new state was still a frontier. Young Machen began his career refining iron with a partner in Lyon County; soon he was successful enough to open his own business. It failed, and he was nearly ruined; but he managed to repay his debts and begin again. He built turnpikes until a severe injury forced him to turn in a completely fresh direction, the law. He never failed again. Soon he had built up a large clientele in the southwestern part of the state, and he became a member of the convention that framed the constitution of Kentucky.

He served as a state senator until the outbreak of the Civil War, at which time Kentucky, a border state, was violently embroiled in

choosing sides. Although the state formally declared its allegiance to the Union, the secessionists, Machen prominent among them, set up a provisional state government. He was elected to the Confederate Congress by residents of his district and by the soldiers in the field. At the close of the war, fearing reprisals, he fled to Canada. His third wife and their young daughter Minnie joined him shortly afterward.

Machen was pardoned and returned to Kentucky. He was urged to accept the nomination for governor of the state but declined because of some confusion about his eligibility. In 1872 he was appointed to the United States Senate, in which he served for four months. At the Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in July of the same year his name was presented by the delegation from Kentucky for the Vice-Presidential nomination. It was a distinction he did not achieve.

By 1880 Machen was a powerful member of the Kentucky railroad commission and his patronage was eagerly sought. He chose to retire to his fine red-brick manor house, Mineral Mount, near Eddyville, Kentucky; it stood on three thousand acres in the fertile valley of the Cumberland River, and there he raised tobacco. The pastoral elegance of Machen’s splendid home must have been somewhat diminished by the running of the Chesapeake & Ohio railroad line past the foot of the hill upon which Mineral Mount was built. Still, Machen had achieved the pinnacle of Southern society, for as both planter and lawyer he belonged to the ruling class. And it was in that atmosphere of privilege that young Minnie grew up.

In a scrapbook which Zelda kept during her girlhood there is a photograph of her mother taken when Minnie Machen was nineteen. Her curling hair is caught up in a braided bun behind her pierced ears, from which fall small jeweled earrings in the shape of flowers. It is a pretty face, which with maturity would become handsome, for it is wellboned and definite. Her nose is straight, her square chin determined-looking, and only the thinness of her lips mars a face that would otherwise have been called beautiful. Beneath the photograph is the inscription “The Wild Lily of the Cumberland.”

Minnie was the artistic member of her family and her poems and short sketches were frequently published in local Kentucky newspapers. She was an ardent reader of fiction and poetry, and when she ran out of books to read she turned to the encyclopedia.

But her dreams centered upon the stage. She had a small clear soprano voice and she played the piano nicely. Her father sent her for “finishing” to Miss Chilton’s School in Montgomery, Alabama. His good friend Senator John Tyler Morgan lived in Montgomery, and it was at a New Year’s Eve ball given by the Morgans that Minnie met a nephew of Senator Morgan’s, the quiet and courtly young lawyer Anthony Dickinson Sayre, whom she would eventually marry.