Lee Krasner (25 page)

Authors: Gail Levin

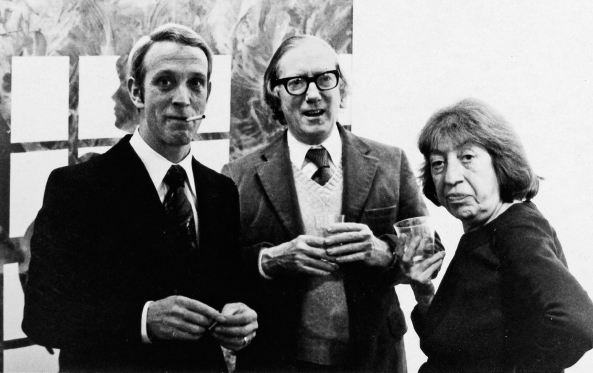

Frank Lloyd, photographed by Donald McKinney. Krasner's near contemporary and a tough businessman who had landed with the British army during the Normandy invasion, Lloyd was said to have twinkling blue eyes that helped to conceal his toughness. Krasner, however, probably recognized and respected his pugnacity because it mirrored her own.

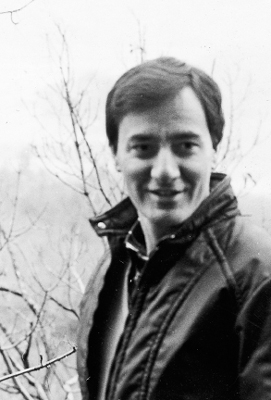

Donald McKinney, the director of the Marlborough-Gerson Gallery in New York, often traveled with Krasner. In February 1967, they took a week's trip to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where she had a show at the university's new gallery there. Photograph courtesy of Donald McKinney.

The art dealer and critic John Bernard Myers, was a close friend of Krasner's. Photograph by Donald McKinney.

Lee Krasner with her friends the artist Terence Netter and the

New York Times

art critic John Russell at an art opening, c. 1977. Photograph courtesy of Terence Netter.

Lee Krasner with her painting

Sundial

with students Laurel Daunis and Cynthia Hall, along with the Fine Arts Department chairman Jack C. Davis, at the Atwood Gallery, Beaver College, April 4, 1974.

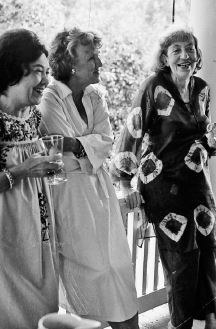

Lee Krasner as artist-in-residence at Marge Schilling's Artists' Conference at Dune Hame Cottage at Watch Hill, Rhode Island. One of the participants, Marjorie Michael, produced a portrait bust of Krasner, which she planned to include in a book called

Valiant Women

. Photograph by Dyne Benner, mid-July 1975.

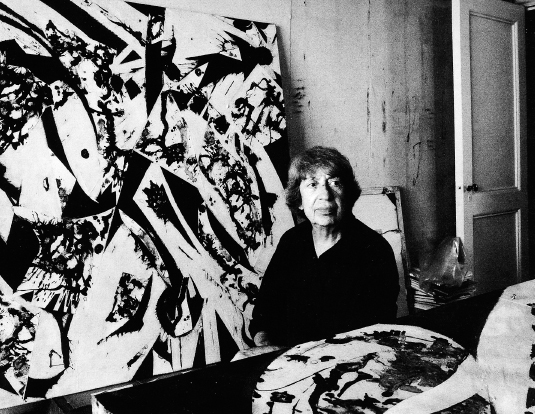

Lee Krasner in her studio in front of an early state of

Crisis Moment

, c. 1972â80, oil and paper collage on canvas;

Butterfly Weed

, 1957â81, oil on canvas, is visible on its side on the left; photographed by Lilo Raymond.

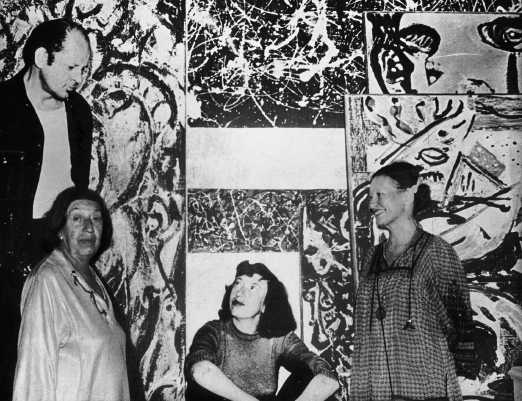

Lee Krasner and Barbara Rose posing before a mural photograph of Krasner and Pollock for the show “Pollock-Krasner: A Working Relationship,” at Guild Hall, East Hampton, August 1981. Courtesy of the

East Hampton Star

.

Lee Krasner with

To the North

(CR 585), 1980, oil and paper on canvas, photographed by Arthur Mones, 1981.

IGHT

A New Attachment: Life with Pollock, 1942â43

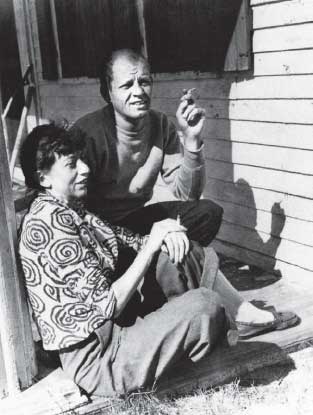

Lee and Jackson in what may be the first photograph of the couple together. Taken at the home of Tillie Shahn, in Truro, Massachusetts, 1944, during a summer spent in Province town, where they socialized with many friends, including those there with the Hofmann School. Photographed by the artist Bernard Schardt, whose wife, Nene, was, like Krasner, a student of Hofmann's.

K

RASNER SAW

G

EORGE

M

ERCER AGAIN IN

N

EW

Y

ORK IN EARLY

January 1942, and afterward he wrote to her: “Miró with you was great fun for me. Then I liked that crazy evening or rather-whacky dine and dance hall we went to up top.”

1

This was the Lafayette Hotel on University Place in the Village, where French food, drinks, and the atmosphere encouraged guests to

linger, as if in a Parisian café. He praised Krasner's dancing and thanked her too “for being such a willing and devoted listener.”

2

For Krasner, however, Mercer, frustrated about art and stuck in the army, could not compete with the excitement Pollock generated with his amazing paintings, rugged sex appeal, and immediate availability.

What had first sparked Krasner's interest in Pollock, their impending joint appearance in John Graham's show “American and French Paintings,” turned out to be all that she had hoped for. It was advertised in the

New York Times

for January 18, 1942, and ran from January 20 through February 6. Graham had chosen to show her

Abstraction,

a canvas from 1941 that was forty by thirty-six inches, in which a still life subject is still intelligible. Distinguished by its bold Picassoid forms, impasto surface, and Mondrian-like heavy black outlines, the painting resembles an approach to Picasso's work already explored by her friend Gorky. “My own excitement around it was overwhelming,” Krasner recalled. “I found myself flanked by a Matisse on one side and a Braque on the other.”

3

Among the other works on view was Pollock's

Birth,

which stood out for its bold forms, colors, and original composition, though Picasso's impact was still apparent. De Kooning showed

Standing Man,

which Krasner said depicted “a young boy, very well dressed, very nostalgic, the image very clear, not abstract at all.”

4

There were also works by Picasso, including

Portrait of Dora Maar, Roses, Femme aux Deux Profils,

and

Femme au Fauteuil.

Matisse's

La Jeune Femme en Rose

was in the show as well, along with works by other Europeans, including Bonnard, de Chirico, Rouault, Modigliani, Segonzac, Braque, and Derain.

Art Digest

wrote about the show: “Most of the Americansâ¦have French leanings, or being primitives, have a naive approach often typical of the School of Paris.”

5

The magazine went on to say, “A strange painter is William Kooning [

sic

] who does ana

tomical men with one visible eye, but whose work reveals a rather interesting feeling for paint surfaces and color.”

6

The magazine did not mention Krasner's painting in the show, but her friends from the Hofmann School took a close look at it, especially Perle Fine, who wrote to say how much she liked it: “It was so much more spatial and the color looked so much richer than anything I had seen of yours previously (and you know how much I liked your other work). It had some real competition, I think, but stood up, Maurice [her husband, the photographer Maurice Berezov] & I agreed, very admirably. We're proud of you.”

7

Despite her excitement about Pollock, Krasner did not immediately cancel all of the connections that she had been building to focus on him alone. She was there when Mondrian's first (and only during his lifetime) solo show opened that January at the Valentine Gallery (run by F. Valentine Dudensing) on Fifty-seventh Street; however, Mondrian stayed away because he had heard somewhere that artists do not attend the openings of their own shows.

8

This disappointed some of his followers who had come to pay homage to him. Nonetheless, his work earned praise in the press.

9

“After the terrible experience Mondrian had in the London blitz he was quite sick,” John Little recalled. Only after Mondrian felt that he had recovered did the Valentine Dudensing Gallery give him his show in January 1942 and invite a few artists “to meet Mondrian and attend a lecture on his theories.”

10

Mondrian's lecture, which Little remembered as having been called “Toward the True Vision of Reality,” took place on Friday, January 23, 1942, and appeared in the newspaper as “The Liberation of Oppression in Plastic Art and Life.”

11

Huge crowds, including Krasner, Little, and many of her other friends from the Hofmann School and the American Abstract Artists, jammed in to hear what Mondrian had to tell them.

12

This lecture was the second in a series of informal meetings

sponsored by the American Abstract Artists.

13

Actually it was a member of the group, Balcomb Greene, who read Mondrian's contribution, in which he reflected on abstract art and how different the intuitive power of adults was from the instinctive capacities of primitives and children. He also explained his theories of composition and how he determined space in his pictures.

14

Mondrian's lecture was later published as an essay entitled “A New Realism” by the American Abstract Artists in their yearbook.

15

Mondrian's art and theories had become known as “Neoplasticism” after he published a manifesto of that name in 1920. His work had been known as part of the Dutch

De Stijl

movement founded in 1917 by Theo van Doesburg. It stressed pure abstraction and universality, reducing subject matter to the essentials of form and primary colorsâred, blue, and yellowâor the non-colors of black, gray, and white. Those in the movement favored asymmetry, while Mondrian liked to limit himself to vertical and horizontal lines. In Paris, Mondrian had joined a broader association of abstract artists (including Kandinsky, Jean Arp, and hundreds of others) founded in 1931 and called the Abstraction-Création movement.

After the lecture, John Little and Krasner went to a party to welcome Mondrian to America at Café Society Uptown, which at that time “was the

in

place in New York and featured the latest music form, boogie-woogie, with Louis Armstrong at the piano and Hazel Scott, the exciting young singer [and pianist]. Mondrian was delighted, and we danced through the night.”

16

Café Society Uptown, the second branch of a successful downtown nightclub, was established in October 1940. The first Café Society, in downtown Manhattan, was written about in

Time

magazine as “a subterranean nightclub” that attracted connoisseurs of jazz. Its founder, Barney Josephson, was said to be “a mild-mannered shoe store owner” from Trenton, New Jersey. Josephson recalled that his aim was to create the “first truly integrated nightclub in this country.”

17

Krasner's friend from the WPA Lou Bunce recalled, “Going and listening a lotâ¦I had known some jazz people, particularly two-beat jazz in those yearsâ¦. We went to the opening of Café Society. There was a friend of mine by the name of Anton Refregier, who did decorations, andâ¦he managed to invite us there and it was our night out on the “town thereâ¦. It was kind of a neat place. It was beautiful. And I remember there was a jazz pianist by the name of Hazel Scott. And she was just absolutely great. That was the opening gun. It was quite an experience.”

18

Krasner's admiration for Mondrian was such that she must have relished the opportunity to mingle with him once again. For her friend John Little, and for other Americans already influenced by Mondrian's work, meeting him was sensational, an event they, like Krasner, recollected for the rest of their lives. Many of the Americans, including Krasner and Little, among many others, had experimented with the master's Neoplasticism, trying out variations of his structure, forms, color, space, and content.

19

But they were also impressed with Mondrian's engaging personality. His enjoyment of boogie-woogie music and dancing also added to the fun. Krasner recalled that they “liked to listen to jazz, and we used to go to a Café Uptown or Café Downtownâ¦and dance.”

20

She considered Mondrian one of her most outstanding partners for dancing. “I was a fairly good dancer, that is to say I can follow easily, but the complexity of Mondrian's rhythm was not simple in any sense.”

21

“I nearly went mad trying to follow this man's rhythm.”

22

Krasner remembered a particular evening with Mondrian at the Café Uptown or Café Downtown. “First, he waited through several numbers for a particular piece that he wanted to dance to,” she recalled. “Then he said, âNow!' and we went around in what I would describe as one of the strangest rhythms I've ever had to deal with. In other words, I had to do major concentration to follow this manâ¦. I noticed lots of heads looking at us and

I thought, âOf course, they're looking at us, because I'm dancing with Mondrian.' Then we swung around a corner and I could see the couple behind us, and it was some movie actor and a divine-looking woman, and that's who were being watched!”

23

American Abstract Artists member Charmion von Wiegand described Mondrian as “a perfect dancer [who] danced in a way so perfect that it was almost too perfectâ¦it was alive.” Another recalled that Mondrian “danced stiffly, with his head thrown back.”

24

Mondrian apparently liked women and once gave this explanation for why he never married: “I have not come so far. I have been too occupied with my work.”

25

Though he had purportedly been in love several times, it was rumored that he had not married because he lacked adequate money and security to support both his work and a wife. Described by some as a “passionate, virile man,” Mondrian, according to von Wiegand, liked to dance to the accompaniment of boogie-woogie, not the melody.

26

Harriet Janis (Sidney's wife) recalled that Mondrian's favorite haunt was “Café Society, Downtown, where he went especially to hear Albert Ammons, Mead Lux Lewis, and Pete Johnson, the Negro boogie-woogie pianists.”

27

Boogie-woogie was considered the least melodic form of jazz and the most technical, and for Mondrian, it related to music in the same way that abstract art related to traditional representational art: “Boogie-Woogie was to jazz what Neoplasticism was to Cubism,”

28

he said. He loved the rhythm.

According to Little, Mondrian's patron (probably Holtzman) invited them for breakfast at Child's restaurant, not far from Mondrian's Fifty-sixth Street studio. From there Krasner and Little headed back to the Village, tired but invigorated by the memorable night out.

Inspired, Mondrian would go on to begin work that summer on his famous canvas

Broadway Boogie-Woogie

(1942â43), which the Museum of Modern Art rushed to acquire in May 1943 and exhibit the following summer. “I especially like the metropolitan

life of New York,” exclaimed Mondrian. “Very noisy, but that doesn't hinder me. I think that in America there is much more general appreciation for the new things than in France and in London. I don't know the reason but it may be that Americans see freerâa very good quality.”

29

For the unfinished

Victory Boogie-Woogie

of 1943â44, where he added some secondary colors, Mondrian relied on both bits of colored paper and small bits of Dennison adhesive tape, which were then produced in primary colors.

30

For one of Krasner's works called

Mosaic Collage

(estimated in the catalogue raisonné to have been produced sometime in 1939â40), she appears to have seized on a jazz rhythm like Mondrian's. She too experimented with mostly primary colors and small bits of colored paper to achieve an optical effect that also vibrates. Though Mondrian rejected curves in his classic abstractions, Krasner employed curves and circles both here and in her other Mondrian-inspired works while emphasizing primary colors, such as in her

Red, Yellow, Blue

of 1939â40.

31

Her single collage of this period is a unique work in her oeuvre and seems unlikely to be related to anything but Mondrian's work.

Mondrian's place in Krasner's thinking is even more evident in Mercer's reply to a letter she sent him in February 1942. “You are right,” he wrote to her about Mondrian. “Piet is wrong. He's cloistered. âGood' and âBad,' pure and impure are equally valid. But then, if we will be ourselves, what can Piet do? His purity makes for impure in paintingâor doesn't it? (One can still like him).”

32

From Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where Mercer was running a camouflage school, he confided his anxiety that America might not win the impending war. Krasner's friendship with Mercer resulted in her close exposure to a reluctant and frustrated soldier's view of the war. Not long after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he reflected his frustration that the United States had allowed Japan to open hostilities and complained that we had been “so blind to the moral condition of Germany.”

33