Lamplighter (46 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

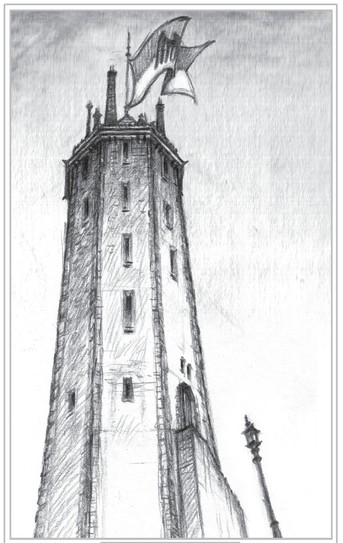

WORMSTOOL

gourmand’s cork

also known as a throttle or a gorge; the projecting “knuckle” of cartilage in a person’s throat, in which is situated the vocal cords; what we would call the Adam’s apple. It is called the gourmand’s cork (a gourmand being one who is a gluttonous or greedy eater) because of the tight sensation you can get there when feeling nauseated, which vulgar folk hold is the voice box trying to prevent or “cork” any further eating.

also known as a throttle or a gorge; the projecting “knuckle” of cartilage in a person’s throat, in which is situated the vocal cords; what we would call the Adam’s apple. It is called the gourmand’s cork (a gourmand being one who is a gluttonous or greedy eater) because of the tight sensation you can get there when feeling nauseated, which vulgar folk hold is the voice box trying to prevent or “cork” any further eating.

R

OSSAMÜND was turned out into the small yard at the foot of Bleakhall the next morning to discover thick fog smothering the land, deadening sound, diminishing light, dampening spirits. There was no wind, not even a gentle breeze; just the clammy touch of tiny, infrequent eddies. In the unsettling quiet the half quarto of lampsmen who were to be his billet-mates, perhaps forever more, said very little above common greetings and introductions. One old fellow, who presented himself as Furius Lightbody, Lampsman 1st Class, checked the two new lamplighters’ harness and their equipage. He paused when he spotted Rossamünd’s salumanticum.

OSSAMÜND was turned out into the small yard at the foot of Bleakhall the next morning to discover thick fog smothering the land, deadening sound, diminishing light, dampening spirits. There was no wind, not even a gentle breeze; just the clammy touch of tiny, infrequent eddies. In the unsettling quiet the half quarto of lampsmen who were to be his billet-mates, perhaps forever more, said very little above common greetings and introductions. One old fellow, who presented himself as Furius Lightbody, Lampsman 1st Class, checked the two new lamplighters’ harness and their equipage. He paused when he spotted Rossamünd’s salumanticum.

“Good lad,” he said. Lightbody tugged on its strap to test the repair, then patted a satchel of his own, showing a hand missing the third and fourth fingers. “Wise. We’ve all got one.”

Rossamünd nodded. “Why are there five of you?” he asked in a hush.

“Them city-scholars say it takes three fit fellows to best a single hob-possum” was the gruff return. “That’s all well and good for them and their books, but out here we reckon five of us stands a better chance. In truth there should be more . . .”

Lampsman Lightbody attached a bright-limn to the head of each of their fodicars, fixing the bottom of the small lamps—known as crook-lights—to the shaft to prevent them from swinging about noisily.

“Why do we not take a leer with us?” Rossamünd wondered aloud, looking worriedly at the thick airs.

“ ’Cause we don’t got one to take,” came the simple answer. “The Hall’s fellow is with his own lamp-watch, and Crescens Hugh—he being our own one-and-only lurksman—is off-watch. Even he needs his sleep.”

Another lighter named Aubergene stood before them. He was a much younger fellow with black hair, angular features similar to Sebastipole’s and a protruding gourmand’s cork that bobbed disconcertingly as he addressed them with suppressed, whispered enthusiasm. “Don’t you fuss too much about this soup, young fellows, it’s just Old Lacey,” he explained kindly. “It’s the fleermare. Comes in off the Swash and leaves everything dripping, but without it there’d be no water for us or the plants—it rains dead seldom about here. Take these . . . it’s phlegein,” he said to Threnody’s blank look at the small tubes the man held out to them, “or falsedawn if you like. In case you lose us. Just pull the hem.” He indicated a small silk protrusion on the bottle. “Strike the raised end on the ground and hold it high, well away from your face.”

Threnody went to refuse, tapping the fine-drawn arrow on her brow, as if it were an answer to everything.

Aubergene looked at the spoor with a slight hesitation. He puffed his cheeks out and in and said, “That’ll help you find us, lass, but not us you. Take it and let us get on.”

Sergeant Mulch led off, and as Rossamünd then Threnody followed the five bobbing lights out the heavy gates of Bleakhall, Rossamünd looked back at the barely visible mass of the Fend & Fodicar. He tried to guess which window Europe slept behind.

Leaving Bleak Lynche, it was impossible to reckon distances between lanterns. In the opaque fumes the beclouded nimbus-light of a great-lamp could be seen only when the watch drew very near. The assiduous lampsmen worked, stoutly feeling their way one great-lamp to the next, each lighter nothing more than the suggestion of a shadow and a bobbing globular glow, communicating only rarely in terse whispers. Rossamünd had never been anywhere so completely blank: anything could leap out and snatch them away. Ears were a-ring with anxious straining, eyes bugging to keep sight of the will-o’-the-wisp gleam of the leading crook-lights. His throat was in a constant constriction of dread; he did not know how the lamplighters of the Frugelle ever managed to do their work without blubbering into an overwrought mass. No amount of practice on the Pettiwiggin could have prepared him for this. It was a relief to learn that neither he nor Threnody was expected to wind any of the lamps on this blind morning. Nevertheless, he waited impatiently for each lamp to be wound,

one—two three—up, down-two-three, one—two—three—up, down-two-three,

cringing at the ringing clatter of the cogs and chains. Though the mechanical sounds were muffled by the turgid airs, Rossamünd found them a clashing of cymbals in the tomblike silence, sure to attract some nasty lurker.

one—two three—up, down-two-three, one—two—three—up, down-two-three,

cringing at the ringing clatter of the cogs and chains. Though the mechanical sounds were muffled by the turgid airs, Rossamünd found them a clashing of cymbals in the tomblike silence, sure to attract some nasty lurker.

The all-too-sluggish encroachment of the new day’s growing light served only to illuminate the fog itself, making it pale and almost phosphorescent; a yawning whiteness where the only tangible thing was the hard-packed road grinding under his boot-soles. This luminous nothingness obliterated any sight of the crook-lights, and forced the lantern-watch to march closer than the regulation spacing.

Suddenly the column stopped.

Rossamünd could sense the lampsmen becoming very still.

The fellow immediately before him—Rossamünd thought it was Aubergene—crouched and indicated the young lighter do the same. Rossamünd obeyed and repeated the motion for the benefit of Threnody behind.

I am the very soul of stillness.

He repeated Fouracres’ old formula.

I am the very soul of stillness . . .

He repeated Fouracres’ old formula.

I am the very soul of stillness . . .

Motionless and listening, he understood almost instantly. Something was snuffling in the veiling murk off to the left, its shuffling movement faint yet obvious in the dry crackle of the stunted Frugelle grasses. Staring out into that awful blank, Rossamünd had a prodigious sense of the malign intent of this sniffling, searching something. He carefully, haltingly, squeezed a hand into his salt-bag, thankful for resorting its contents. He felt for the especially wrapped john-tallow—one of the unused gifts bestowed by Master Craumpalin when Rossamünd was still a foundling starting out. He withdrew it with fastidious care lest the oiled paper make a give-away rustling of its own. Working it free of the bag, he put the parcel on to the road and gingerly grasped two corners of the complex folds of the wrapping, careful not to touch the actual wax. All this he did by feel alone, his eyes busy looking into the impenetrable fog, darting left and right at each new noise.

Before him he could hear Aubergene ever-so-gently cocking some kind of firelock.

The snuffler was getting closer.

On the other side, Threnody was a hardly discernible shadow—was that her arm he saw reach for her temple?

With a sudden flick of wrist and fingers, Rossamünd pulled the wrapper apart, letting out the sweaty, unwashed smell, and, quick as fulgar’s lightning, flung the john-tallow, packaging and all, out into the cloudy soup. He could almost feel the attention of the malignant stalker catch the smell and follow the invisible arc of the flying repugnant. Sure enough, the sounds of scuffling moved away.

Oh, glory on Craumpalin’s chemistry!

Rossamünd’s heart sang.

Rossamünd’s heart sang.

Aubergene did not appear to notice the young lighter’s action and the lighters stayed as they were for longer yet—Rossamünd’s senses frayed, his haunches aching—till as a man, they decided it was safe enough to push on. Not one mention was made of his deed; none had noticed.The young lighter had no way of knowing if it

was

the john-tallow that drew the sniffing thing away, and therefore he kept any boasts to himself.

was

the john-tallow that drew the sniffing thing away, and therefore he kept any boasts to himself.

Unexpectedly, only two lamps later, the vertical bulk of Wormstool materialized—they were arrived at last. The cothouse—if it could be called a “house”—was a tall octagonal tower topped with a flattened roof of red tiles a-bristle with chimneys. Entry was gained by the ubiquitous narrow flight of stone-and-mortar steps that bent about three faces of the tower as it climbed to a second-story door.

Rossamünd held his breath and squinted against the noxious fumes drizzling from the smoldering censer at the foot of the steps.

At the top, the thick cast-iron door opened on to a watch room. Entering, Rossamünd found an eight-sided hall, the walls slitted with loopholes, where watchmen periodically wandered from one to the next and mutely observed the land beyond. Not even the entry of the lantern-watch distracted them from their lookout.

In the very middle of the hall was a squat lectern, and behind this sat an uhrsprechman. Wet-eyed, limp-haired, the man looked all too ready for sleep, shuffling and settling papers clumsily at the close of his night-vigil. He watched the arrivals hawkishly, screwing up his face as he tilted his head back and peered over his glasses.

“ ’Allo, Whelpmoon,” the stocky, hairy under-sergeant named Poesides said to the fellow as they passed. “Ye look a mite piqued, me old mate. Just be glad you’ve not had to be out

there

this mornin’: pea soup so thick that a laggard couldn’t scry through it—and a stalking lurker thrown into the bargain.”

there

this mornin’: pea soup so thick that a laggard couldn’t scry through it—and a stalking lurker thrown into the bargain.”

Whelpmoon nodded briefly, said nothing, and kept at his staring.

Looking beyond him, Rossamünd saw a great kennel occupying three whole walls which kept a pack of dogs: spangled whelp-hounds—giant, sleek-looking creatures that eyed Rossamünd suspiciously and let forth warning growls from their heavy-barred cage.

“Them daggies never takes to strangers,” Lampsman Lightbody chuckled.

From this room the lampsmen gained access to higher floors by a wooden stair at the left of the entrance. From it dangled a sophisticated tangle of cords and blocks, much as could be found on a vessel. Rossamünd asked what these were for.

“Ah,” answered Lampsman Lightbody eagerly, “these stairs are the genius of the major and Splinteazle our seltzerman—naval men, both of them, with cunning naval minds.” He nodded approvingly.

WORMSTOOL

Rossamünd’s ears pricked at this mention of the Senior Service.

“It’s dead-on impressive,” Aubergene added. “You see there—that cord, how it leads up through that collet in the ceiling? If ever a nicker or some other flinching hob makes it in here and we need to retreat, we can pull levers up on the next floor connected to that cord and cause this whole construction to topple, leaving the foe stuck down here while we ply fire from on high.”

It was indeed “impressive”—as an idea at least. No sooner had Rossamünd ascended a few steps than the whole flight wobbled alarmingly, beams groaning, the rope tackle shaking. The lighters did not seem to notice, and climbed happily up to the floor above, while Threnody and he followed one careful step at a time, knuckles whitening on the worn-smooth banister.

Gratefully achieving the top, Rossamünd heard Aubergene declaring, “Our reinforcements all the way from Winstermill, sir—ain’t it nice to know we’re not forgotten?”

Rather than dwelling safely on the very top floor of the tower, as many officer-types might, Wormstool’s Major-of-House held office in the very next level; working with his day-clerk on one side and cot-warden on the other, all seated behind the same wide desk of thick, hard wood. It looked solid enough to serve as barricade and fire-position should need arise. Rossamünd could well imagine musketeers firing from behind it with their firelocks, shooting at some intruder who had managed to win its way up the rickety stairway.

The house-major was even better turned out than his subordinates—creaseless platoon-coat of brilliant Imperial scarlet and a black quabard so lustrous, with its thread-of-gold owl, it almost gleamed. The man was most certainly of a naval bent, for there were several scantlings of main-rams and cruisers pinned to the angled walls about him and a great covering of black-and-white checkered canvas on the floor, such as Rossamünd would expect to find in the day-cabin of a ram. The house-major stood with a fluent, perfectly military motion.

“Miss Threnody of Herbroulesse and Rossamünd Bookchild, Lamplighters 3rd Class, come from Winstermill Manse, sir,” Rossamünd said firmly as he stepped before the immaculate officer.

The house-major fixed them with mildly skeptical amusement. “Well, aren’t you a pair of trubb-tailed, lubberly blunderers?” he exclaimed in a trim and educated accent that gave no hint to his origins. “We’ve not received a brace of lantern-sticks in a prodigious long time, and neither have we received word to be expecting any! The dead of winter means infrequent mail and is an off time to be sending anyone so far—how long have you been prenticing for? I thought lantern-sticks weren’t deemed fully cooked till chill’s end.”

Rossamünd and Threnody looked to each other.

Threnody spoke up. “We were told that Billeting Day was done early because the road was in need of new lighters.”

“Is that rightly so?” Taking his seat, the house-major stared at her and, more particularly, her spoor. “It is not common to have one of your species make lighter, especially not one that is a tempestine too—are you not a little too new from the crib to be cathared?”

Other books

Rumor by Maynard, Glenna

Toxic Part One (Celestra Series Book 7) by Moore, Addison

Forgive Me, Alex by Lane Diamond

Cop Town by Karin Slaughter

High on a Mountain by Tommie Lyn

Blyssfully Undone: The Blyss Trilogy - book 3 by CLIFF, J.C.

Strong as Death (Catherine LeVendeur) by Newman, Sharan

Lady of the Butterflies by Fiona Mountain

Emily French by Illusion

The Malhotra Bride by Sundari Venkatraman