Kleopatra (34 page)

Authors: Karen Essex

From: Hammonius in the city of Rome

To: Ptolemy XII Auletes

I hope this finds you well and happy in Ephesus, and thank the gods you are not in Rome. The last months have seen violence

beyond our measure. Pompey got tired of being the victim of Clodius’s mob tactics and has formed a mob of his own under Milo.

This week, they clashed in the Forum, and Cicero’s brother Quintus almost perished in the fray. He hid under the bodies of

two dead slaves until the atmosphere calmed. Cleaning crews are still mopping up the blood.

Your Majesty, it is the strangest thing. After one year of lethargy, suddenly Rome’s most powerful men see profit in reinstating

you and vie for the honor, Pompey (imagine a stance from him!) has petitioned the senate to restore you himself. I suppose

that having Milo’s gladiators at his disposal has made him once again brave. They say he is tired of things in Rome and longs

for another eastern campaign. It is also speculated that a victory in Egypt would provide a nice counterbalance to Caesar’s

impressive conquest of Gaul and Briton.

Meanwhile, Caesar has sent letters to the senate saying that he will gladly take the burden of Egypt from their shoulders.

Everyone knows that he acts due to pressure from Rabirius. The two of them see nothing but money. Not wishing to be left out,

Crassus has also petitioned to go to Egypt with an army to restore you. Crassus is very jealous of the military glories of

Caesar and Pompey. Though he is extremely wealthy and getting on in years, he is determined to compete with his fellow Coalition

members for military greatness. He has so much money that it is likely that he will get his wish.

Finally, my king, one of the gods interceded on our behalf. Yesterday morning, the statue of Jupiter was struck by lightning,

which the Roman diviners took as a great portent. As you know, they report all sightings of lightning to the governing bodies,

who act or decline to act that day according to the omens. The striking of the statue caused great concern. The Board of Fifteen,

led by Cato—who is back from Cyprus—marched solemnly to the oracle, where the Sibylline Books were consulted. In them was

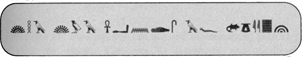

found the most unusual advice:

Restore the king of Lgypt, out do not use a multitude of force.

From the oracle they marched in procession to the Forum, where Cato read the words aloud. By the end of the day, it had been

translated into Latin and posted throughout the city. Still, no one had a satisfactory interpretation.

Cicero—back from exile, his new house full of blond-haired slaves sent as a gift from Julius Caesar—is the one who solved

the Sibyl’s conundrum. Cicero has advised that the military man Lentulus, an honest man, should escort you back to Alexandria,

but must leave you outside the city and march in with his troops. Then, when he is certain the city is secure, he should bring

you home. Force would be used to take the city, but reinstatement would occur afterward in a peaceful manner. The senate is

pleased with the plan, so that when you return home, you will have the orator to thank.

You will soon hear from Lentulus, and you must quickly acquiesce to whatever he proposes regardless of price. (Count yourself

lucky-Caesar, Pompey, or Crassus would have demanded more for their services.) You have often said the gods are with Rome.

It appears that they are also now with you.

Please give my love to the princess. Tell her to prepare for the voyage home.

Kleopatra was lightheaded. She had fasted the night before to purify herself. This would be the first time she paid for a

sacrifice out of her private purse, and the first time she would make the kill. She wanted to be certain that the goddess

Artemis knew her precise intentions and did not confuse her prayers and offerings with those of the king.

The temple was empty except for the princess and the young priestess. The priestess washed the lamb with holy water while

the princess remained in silent meditation, trying to mask her fury with words of supplication. After weeks of anxiety waiting

for word from Lentulus, her father had been contacted instead by Gabinius, the Roman governor of Syria, who had demanded the

usurious sum of ten thousand talents for marching his troops from Syria to Alexandria and toppling the government of Berenike.

Auletes, frantic to return home, agreed. Now the king complained daily of an ulcerous stomach, for he did not know how he

was to make peace with Julius Caesar over the earlier debt, much less raise the money for Gabinius.

Kleopatra knelt before the immense statue of the goddess and prayed with a new fierceness.

Lady Artemis, goddess of young women, of maidens, of the creatures of the forest, accept this small sacrifice. I beseech you

to expand the riches of Egypt. If you so bless my kingdom, I promise that when my time comes, I will not sit on the throne

like my ancestors, draining the country to keep myself in power. I will not walk the floors at night like my father, wondering

how to fulfill the extortionists’ ransom on our country. I will succeed where they have failed.

Why did the gods allow one who had served them so well as Auletes suffer this endless humiliation? Kleopatra and her father

had waited and waited for Lentulus, Auletes becoming more and more dejected by the day. What had happened to this Lentulus,

this honest man, she asked the goddess, whose name had inspired so much hope? Why was he replaced by the greedy pig Gabinius?

Divine Lady, do the gods not exceed the Romans in power and strength?

Hear my vow. Lady, I will never retreat from this position: I will happily face death rather than live a life devoid of dignity.

This I swear before She who hears and knows all Death before humiliation. Death before supplication before the might of Rome.

She fell prostrate in front of the statue, hugging the hard tile floor with her body, murmuring the promises over and over.

Tears streamed onto the goddess’s feet until Kleopatra’s face rested in a cold wet puddle between Artemis’s heels. Exhausted,

she raised herself upright.

“Are you ready, Your Highness?” asked the priestess. Wearing the short hunting tunic of the goddess, she did not seem much

older than Kleopatra. She was an unmarried Greek woman, an anomaly in a country where women had no other function than to

wed. Unlike the Romans, who demanded chastity from their priestesses, the Greeks only demanded chastity from the priestesses

of the chaste goddesses.

Kleopatra caressed the white wool of the animal and looked into his unsuspecting, watery eyes. How could anything be so soft?

She had heard from the Arab people that the softest fabric on earth was from the chin hairs of a particular kind of mountain

goat raised for the sole purpose of donating its wool to blankets made for their king. She would have to procure such a thing

herself someday, for she loved such luxury.

She stopped touching the animal. She was queasy in the stomach, either from lack of food or from the pressure of the vows

she had just made or from anticipation of what she must do to the small lamb.

”Your Highness looks a little sick,” said the priestess.

The color of humiliation invaded her cheeks, giving her away. She was not able to hide her emotions from the woman. This would

not do. No, it would simply not do to have commoners, even if they were priestesses of the goddess, able to read her thoughts.

She must be even more mysterious than the mystics. She looked away from the priestess and, without pause, pulled back the

head of the lamb. Ignoring the way his soft wool felt between her fingers and the last bleating gasp of protestation, she

slid the knife across his throat. The kill was not easy. She had to use more strength than she had anticipated as she ripped

across the supple neck of the small creature, closing her ears against his cry and her eyes against his stunned expression.

The blood came spewing from the neck vein with such force that the priestess had to push the bowl forward to catch it. Kleopatra

watched the blood spill into the bowl like a long red tongue. She dropped the animal and looked straight ahead, not wanting

to meet its open lifeless eyes.

Damnation to Gabinius. Damnation to Pompey. To Rabirius. To Cicero. To Julius Caesar. To all those Masters of the World who

had caused her father and her people so much pain. Those barbarians who made the descendants of Alexander lie down and weep.

Goddess, holy virgin who rules over vast lands, watch over me. I am of Alexander, of the highest and most noble Greek blood.

We are your subjects, your chosen, your people. Abandon these Romans who steal everywhere from us, our money, our poems, our

art, and our very deities. Do they not call you Diana? Who is Diana but a Roman fantasy, a Roman bastardization of something

pure and Greek? Lady, I ask you to consort with your fellow deities and protect us, the original and true people who serve

you

.

The priestess raised her head from the posture of supplication and looked into the eyes of the princess. “Your Highness, the

goddess has received your prayers and your sacrifice. Whatever you ask is done.”

THE TWO LANDS OF EGYPT

B

erenike IV Ptolemy, you are accused of murdering your stepmother, the usurper Kleopatra VI Tryphaena, and of illegally assuming

the monarchy. Further, you are accused of the murder of the philosopher Demetrius and of the eunuch Meleager. How do you plead?

Guilty or innocent?”

“Meleager committed suicide,” Berenike corrected, her black robes of mourning stark against the chilly marble podium for the

accused. She had cut off her chestnut brown tresses as a funereal offering to her husband, an enemy of the state whose body

had yet to be buried. Shorn of her hair, stripped of her weapons and her adornments, she seemed, to Kleopatra, more powerful.

As if peeling her down to her essence revealed the source of her strength.

“That is not a plea,” the magistrate shot back at her.

Kleopatra sat next to Archimedes, craning her neck around his shoulder to see her father’s face. The king witnessed the trial

from his usual box seat surrounded by those whom the general Gabinius had told him were his supporters—including the Roman

moneylender Rabirius, who had insisted on coming to Alexandria to be sure of collecting his debt. Draped in commodious Greek

robes, Rabirius’s rouged and flabby cheeks were framed by unreasonably long curls, still imprinted with the crease of his

crimping iron. He sat next to the chiseled military man Gabinius, the pair looking curiously like a long-married couple who

had aged in opposite ways; one given to cosmetics and bloat, and the other, gaunt, his skin as brown and spotted as an antique

scroll.

Berenike cocked her head like an amused coquette. “Does it matter how I plead? This trial is a mockery staged for the amusement

of my father. I will not plead. I choose not to plead at all before the bastard king.”

”I will give you another chance to enter a plea and to save yourself. Berenike IV Ptolemy, how do you plead before this court?”

Berenike ignored the magistrate and addressed her father. “What a fool you are, Father. I know about the money you paid the

Roman to arrange my demise. Do you think you were the first Ptolemy he approached to fill his pockets with our gold?” She

waved at Gabinius as if acknowledging a long-lost acquaintance.

She continued, “Let us dispense with this travesty. Father, hear this: Gabinius and I have been in close communication since

before he left Rome for his governorship in Syria. The Roman wished me to marry a co-regent from Syria so that he could extort

money from yourself. But he was coarse and ignorant and not fit for my bed so do business with me, as long as I was willing

to pay. You do know how that system works, do you not, Father?”

A low mumble slithered through the crowd, but was silenced by the booming voice of Gabinius. “Will no one quiet this girl

and her lies? Your Majesty,” he began. “Surely you will not allow the words of a traitor to vulgarize these proceedings.”

”The defendant may continue,” said the magistrate. “Unless the king wishes to object.”