Kinglake-350 (10 page)

Authors: Adrian Hyland

To the members of the public who stare at that fire coming in, it seems that the gates of hell have opened. But what does it look like to the professionals?

There is at least one experienced, qualified, professional fire manager who’s positioned himself directly in the path of the inferno: Acting Ranger in Charge of the Kinglake National Park, Tony Fitzgerald. And even for him, a man who’s been working with fire for more than twenty years, it’s a frightful experience, one that comes close to claiming his own life.

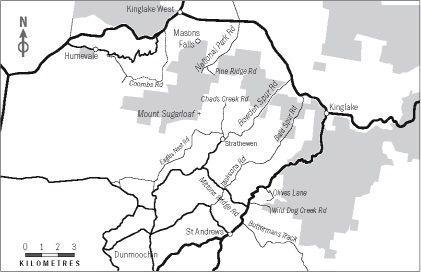

Around 5.30 pm he’s standing on Mount Sugarloaf with one of his team, Aaron Redmond, staring out over the hills and valleys below. Wondering how long they have left. Aaron is nineteen; he’s only recently joined the DSE, but has been a member of the CFA since he was twelve. He knows fire. The two men have gone up there to get an idea of what it is doing, are horrified at the situation unfolding before their eyes.

They are looking directly down upon the destruction of Strathewen. They see the inferno rolling over the town, the spot fires and fingers of flame heading in their direction. They hear the local CFA captain, Dave McGahy, as he sends his crews into action.

‘Godspeed to you all.’

‘Godspeed? Not the sort of language I’ve ever heard on the radio,’ Fitzgerald comments later. ‘It sounded like something you’d say to someone when you feared you were never going to see them again.’

‘Doomsday language,’ adds Aaron.

Appropriately so, as it turns out: of the 120 houses in Strathewen, only sixteen will survive. One of the twenty-seven victims in the town is a member of McGahy’s crew.

There are experienced emergency services personnel in Kinglake West who cannot speak highly enough of the DSE’s work on Black Saturday. Fitzgerald was the first to warn them of what he feared was coming, and he and his crew risked their lives to defend their section of the community. Frank Allan from Kinglake West CFA rang the Kangaroo Ground Incident Control Centre around 2 pm to get more information on the plume of smoke he was watching from the driveway of his brigade, and was stunned that nobody there seemed to be aware of it. He assumes they were so busy looking at screens they hadn’t even stepped outside to look at the sky.

Tony Fitzgerald wasn’t relying upon computers or other equipment but on his own awareness—a knowledge of the way fire works, of the topography, the fuel loads, even his reading of the winds to predict the timing of the change.

It was an awareness based on more than twenty years of making fire his business. He understands fire at a theoretical level, with a degree in ecology, majoring in botany and geography from Melbourne University. But more importantly, he’s been working at the coal—or fire—face since 1983. He was recruited to Kinglake primarily to work as a fire manager, and in the fifteen years he’s been there has managed controlled burns on thousands of hectares, as well as holding command roles in some of Victoria’s biggest bushfires.

It isn’t until Fitzgerald comes into the Kinglake West station and tells them that according to his gut instinct the fire is going to hit them in about two hours—which it does—that the CFA has the first inkling of what they are in for. They make good use of the warning, ringing around various contacts in the community to alert them.

Fitzgerald makes an arrangement with the CFA: he’ll look after the section of land along the National Park Road. He has a crew of eight firefighters in two ‘slip-on’ utes. After leaving the CFA, they race down National Park Road, knocking on doors, stopping cars, warning as many residents as they can contact. Then they take up a defensive position along the crest of the gorge near Masons Falls. Fitzgerald gathers his crew together, explains that they’re about to undertake the most dangerous operation a fire crew can perform and gives them the option of leaving, returning to their homes. None do.

Whatever steps he and his crew take will be dwarfed by the magnitude of the blaze, he knows that. But they have to do something. At best, his hope is that they will be able to make some sort of attack on the fire as it crests the escarpment, take the sting out of it. There are some hundred houses behind them: if he can reduce the fire’s intensity, it will increase the occupants’ chances of survival.

Fitzgerald has earlier received a call from Steve Grant, his boss in Broadford, warning him that the incident control centres are barely functioning and that he and his crew are on their own.

Fitzgerald and Redmond have gone up to Sugarloaf to get a better view. They are there when the wind change comes through. Burning debris begins to bombard the slopes directly below them.

A piece of burnt bracken lands at their feet. Aaron stomps on it almost casually, then thinks, Hell, if the embers are coming this way… Fitzgerald has the same thought. The clifftop lookout is no place to be; the fire will be on them in minutes. They hurry back and join their colleagues.

Fitzgerald has already discussed the options with his 2IC, Sean Hunter. The first is to beat a retreat; the crest of the escarpment will be where the fire is at its most lethal. The other, infinitely more dangerous, option is to attempt a backburn.

The creation of a backburn in the face of a firestorm is about as delicate and dangerous a task as a firefighter can attempt. The theory is that you burn a line just before the main front, timing it so that your fire will catch the convective wind and be drawn into the advancing flames. As the main fire hits the burnt area, it should lose some of its intensity. The timing is critical: too early and your own fire could come back at you, too late and the inferno will overrun you.

Fitzgerald knows that the operation has only a slight chance of success, but feels he has to do it. If it works, it could reduce the impact of the fire upon the houses on National Park Road, saving lives and property.

He positions his team in a line of maybe seventy metres, waits for the slim window of opportunity. The tension is electric: a tiny crew with not more than a couple of utes for protection strung out across a ridgeline waiting for an inferno to fall upon them.

Aaron is struck by the smell in the air: a pungent mixture of smoke and eucalyptus vapour. There is a period of stillness. The fire is approaching, sucking the air in with such force that it cancels out the ambient wind.

Fitzgerald studies the bush intently, searching for the signs, and suddenly sees what he’s been hoping for. A stirring of leaves on the ground, a tug of wind from behind their line. It gathers strength, as he’d hoped it would: the speed of the convective wind increases with its proximity to the fire.

The crew members glance at each other, anxious, waiting for the signal. ‘Wouldn’t say I felt afraid,’ says Aaron. ‘Just focused. We had a lot of faith in Tony.’

He is amazed to realise that he is standing in two different layers of wind simultaneously. The air around his upper body is perfectly still, but the debris on the ground is being sucked towards the unseen fire, leaves and embers tumbling in the opposite direction to the way they were blowing shortly before. The leaves accelerate; the fire is coming closer. Still invisible, but the signs are there.

Fitzgerald knows the moment has arrived. He gives the order, and his crew apply their drip torches. A line of fire springs up. An anxious moment—which way will it go?—then Fitzgerald is relieved to see the burn take off and begin to move towards the ridge. The gamble is working.

Sean Hunter, closer to the edge, starts waving frantically, and Fitzgerald sees a sixty-metre burst of flame roar out of the gorge directly in front of them. Almost simultaneously one of the houses behind their line erupts into flame with a suddenness that shocks him. In seconds, there are some thirty spot fires flaring around them.

Their position has suddenly become a death trap: the fire is vaulting right over them. Fitzgerald orders the crew to retreat to a pre-planned anchor point, a safety position. The flames are leaping over their heads. Aaron is aghast to see blue flame run straight up into the crowns.

They sprint for the cars. One crew don’t even have time to roll up the hose; they clamber aboard and race away with a thirty-metre length of hose snaking wildly behind them. A possum, partly burnt and panicking, has the misfortune to pop up onto a rock and is flattened by the swinging hose.

They regroup some two hundred metres back at the corner of National Park and Pine Ridge roads, shelter there for a few minutes and wait for what they take to be the main front to pass. Fitzgerald instructs the crew to do what they can to tackle the spot fires igniting around them, while he and fellow ranger Natalie Brida drive back into the smoke to reconnoitre the area they’ve just evacuated and see if there’s anything in there they can save.

He drives in slowly, carefully, nerves taut. To his relief and surprise, the half-dozen buildings are still standing, albeit under severe ember attack. Has the strategy worked?

The sky turns a sudden, luminous orange.

‘Oh shit!’ This fire is behaving like nothing he’s ever encountered. What he took to be the main front was only the preemptive strike. The worst is about to come. Any second.

They have to get out of there fast. He slams the car into a U-turn, has just managed to complete it when the full fury of the fire’s radiant energy blasts into them. The fire is crowning directly overhead. ‘It was an absolute furnace,’ he commented later.

The world is plunged into darkness. A branch flies out of nowhere and smashes the headlights. He feels the radiant glow burning the side of his face. He can barely see a thing, but he knows this patch of road intimately; his house is just up the road, and he’s walked it nearly every day for the past ten years.

If I don’t get us out of here, he tells himself—and he’s one person who knows what he’s talking about—we’re dead.

He aims at where he hopes the gates are and revs the guts out of the motor. Nothing much happens. The blast of heat has apparently knocked out the electrics. ‘Come on, baby,’ he whispers to the Toyota.

The ute takes off, but slowly, walking pace; they go crawling, grinding and shuddering down the road. The fireside tyres are burnt, and he’s driving on the rims. The tonneau cover catches fire. Fitzgerald is relying on adrenaline and memory, heading for where he figures the gates are.

Aaron, back with the rest of the crew and frantically fighting the fires breaking out around them, hears Natalie on the radio saying their lights are blown out.

Why don’t you just replace the fuse? he thinks, and is stunned to see the boss’s car come crawling out of the darkness, limping and flaming, one side completely black. He’s struck by the look of desperate determination on Fitzgerald’s face. Not even pausing to grab their bags, the occupants leap from the burning vehicle as it is overwhelmed, scramble aboard the slip-ons.

The rendezvous is outside Fitzgerald’s own home. He’s dismayed to see it’s already on fire. He stares at it, momentarily stunned. Finds time to be grateful that his wife, Kerry, and their two primary-school-aged children left that morning—the first time they’d ever evacuated. ‘If I’d been on my own, I probably would have had a go at saving the place, ’ he says later.

But when he makes a move Sean shakes his head. ‘It’s gone, mate.’

From there, the crew fight a running battle down National Park Road—helping wherever they can, warning people to get out, assisting others to defend their homes. Fitzgerald sends Natalie out to the intersection to stop people coming into the road; some take her advice, some don’t. Some of those she speaks to will die soon afterwards on the road to Kinglake.

Aaron Redmond, also in the roadblock team, is amazed at the chaos that suddenly erupts. Most people are scrambling to flee the area, but some are trying to get back in, either to protect their homes or do the most ludicrous things: somebody wants to retrieve papers he’d left on the kitchen bench, another wants to get his tablets. Aaron recalls thinking, ‘You won’t be needing your tablets if you go back in there.’

The Community Emergency Response Team—a local volunteer ambulance crew in a small Subaru—turn up, responding to a 000 emergency call from back in National Park Road. The DSE crew try to escort them back in, but the track is completely engulfed, impassable.

Of the hundred or so houses along that road, very few survive. In that intense kilometre closest to the Gorge, only one does.

As the main front overtakes them, the crews retreat to the relative safety of a ploughed carrot field, watch helplessly as the fire roars around them into the community. As soon as it passes, they move out to see what they can do to pick up the pieces.

Fitzgerald knows he’ll be driving into a human tragedy. But it will hit closer to home than they expect; one member of the team, Tom Chambers, is to lose two sisters in the disaster.

Tony Fitzgerald learned his craft from an old forester named Fred Whiting, and he reminisces fondly about the apprenticeship. ‘Here I was, just a fresh-faced kid, working on a fire crew in Gippsland. They were tough men, wouldn’t give you any second chances, especially if you were from university. They’d been working with fire for generations. Fred was nearing retirement then, and he took me under his wing. He wanted to teach, I wanted to learn.’

Fred Whiting had a telling nickname for a bushfire: he called it the Boss. ‘“What’s the Boss doing?” he’d ask. “Where’s he think he’s going?” And it is like a boss—it can crush you any time it wants. That’s the first thing I learned: the fire’s always in control. You have to respect it. You can bomb it or bulldoze it all you like, but it can turn on you any time. Sometimes you can play round with the boss, swing him round to your way of thinking. If he’s in a good mood, maybe he’ll go along with you. But when he’s on the rampage—look out! Get the hell out of there!’

Tony Fitzgerald sees a lot of things in a fire, but one of them is a challenge, a mystery you have to call upon all your experience and guile to unravel. He thinks about fire the way you imagine a racehorse trainer thinks about a recalcitrant thoroughbred that shows a glimmer of promise.

‘When you’re looking at a fire,’ he explains, ‘you’re thinking, Can I bring it round to my way of thinking? Can I use more fire to coerce it? Maybe put in a fuel break, guide it towards a natural obstacle, a creek or a gully.’

Fred Whiting has been dead for many years now, but Fitzgerald still speaks with great respect for the old master burner’s way of working. One aspect of Fred’s modus operandi that he has come to appreciate more with the passing of the years was his deliberation. From Fitzgerald’s description, he almost sounds like Roger Federer lining up a backhand passing shot: there’s an awful lot going on real fast, but to the onlooker, he’s got all the time in the world.

The Gippsland team might have been on a routine job when there’d be a sudden outbreak, a fire whirl or a flare-up from a larger conflagration.

‘I’d be doing a song and dance,’ says Fitzgerald, ‘wanting to do something. And Fred would just get out the tobacco and roll a smoke. Always. Probably take a good two minutes. He’d be doing more than lighting a smoke, of course; what he was doing was watching— he knew there was no point doing anything until he’d done an assessment. You don’t do that, you’re liable to make a mistake. Maybe a fatal one.’

Fitzgerald doesn’t smoke, but he has absorbed the lesson: the need to stand back, study the situation, use your experience to work out what’s about to happen. That’s what he was doing on top of Mount Sugarloaf, and it’s a lesson he’s attempted to pass on to the generation coming up behind him.

Much of what he’s looking at involves the wind.

Of course there are a lot of other things you need to know—the topography, the vegetation, the fire history—but when the crunch comes, wind is the vital component. Not just the ambient wind, but the wind created by the fire itself, the convection wind.

‘The fire sends up a convection column,’ he explains. ‘The hot air rises. The effect is like a bicycle pump, sucking from above; air is pulled in from all around.’

This was the reason for that eerie stillness so many felt just before the fire struck. The convection column was so powerful that it was dragging in the north-westerly gale that was driving the fire, negating its momentum.

‘We were in the lee of this huge plume of convection, north-west of where we were, and it was sucking in the dominant wind,’ says Tony Fitzgerald. ‘Convective wind is the fire manager’s stock in trade. That’s what Fred was looking at. It’s the fire’s way of talking to you. You have to understand it and use it to your advantage.’

That wind blowing around Aaron Redmond’s feet was the convective wind in action, air being sucked into the inferno to replace the air that was rising in the column.

Wind, of course, is just one of the things the fire manager is studying. ‘You watch the way the smoke moves, the way the flames are being fanned. Is it running up the trees? Racing through the crown? Is it shearing?’

Sometimes, like the Vedic Indians or the ancient Slavs, Fitzgerald talks about fire in almost anthropomorphic terms. ‘You get two convection columns hitting each other—maybe from two different ridges—and at some stage they’re going to fight it out. They’ll push, pull, twist each other, and you’ll get this interaction between the two. That’s when you get whirlwinds, roofs lifted, trees sheared, corkscrewed out of the ground.’

While Tony Fitzgerald and his crew were fighting for their lives on the edge of the escarpment their colleague, Ranger Cam Beardsell, was at Dunmoochin down below, watching it run up at them.

‘Cam said it was like a wave that rippled up the ranges: flame sheeting above the tops of the trees in a continuous pulsing motion. It would move, stop, roll forward, pause again’—presumably it was pausing to devour the fuel within reach—‘then it would go skipping over the tops of the crowns.’

Liam Fogarty, the DSE’s Assistant Fire Chief, is another who has made fire his life’s work. Like Fitzgerald, he worked on fire crews in his youth, learning from the old hands before he went to university. Fogarty has worked as a senior scientist in places as diverse as Indonesia and New Zealand. Expanding upon the intensity of the convection process, he comments that one of the most fascinating aspects of convection in a megafire is the size of its footprint.

‘The fire might be burning across a five-kilometre front,’ Fogarty explains,

but because of the drought, the humidity and the three desiccating days the week before, fuel from a much broader area—five to six times that distance—was contributing its energy to the blaze. In parts of the affected area, the fuel load would have reached thirty to forty tonnes per hectare. The first rush of the fire would have incinerated the fine fuel— twigs of less than six millimetres, leaves, dry grass. Then the heavy fuel—logs, branches and so on—would ignite, and keep burning for another twenty minutes to half an hour.

All of this contributes to an eruption of gaseous hot air that could blast as much as a kilometre out from the fire. The heat wave is a result of both convection and radiation, and it is composed of burnt and unburnt products of the combustion, including gases—known as pyrolysates—from the thermal degradation of cellulose and hemi-cellulose. That’s the technical aspect.

The un-technical aspect is that it can kill you. Convection means that the column’s natural direction would be upwards. But because of the ferocity of the wind on Black Saturday, it was forced down, lashing out like a chameleon zapping insects.

This also explains one of the things that puzzled firefighters in the aftermath: why many of the victims did not appear to be burnt, why one poor soul, for example, died untouched in the middle of the Strathewen football oval. It is because a fire like this will not merely burn its victims, it will often asphyxiate them, sometimes from great distances—up to five or six hundred metres.

The St Andrews firefighters were struck by the number of people who died immediately after the wind change. ‘It was like a vast wave of heat had swept up Jacksons Road in seconds,’ commented one member. ‘If you were indoors you were okay, if you were out in the open you were dead.’

As the fire gathers intensity, it throws out embers and burning brands—initially, maybe three or four kilometres ahead, then further as it grows. These will ignite new fires, which will in turn feed their energy back into the main blaze—sending out more incendiaries. And so it storms forward, gathering strength, a self-sustaining cycle of destruction.

‘There isn’t enough oxygen in the fire,’ explains Fogarty:

The fire is sucking air in, trying to burn all this fuel, but it can’t—so all these gases start to accumulate. The vaporised eucalyptus oil will be captured there. Finally when enough oxygen comes in, it will suddenly flash and flare and burst up above the fire.

What Fogarty is describing are the ‘fireballs’ that filled so many witnesses of the inferno with dread: they aren’t so much ‘balls’ as massive bursts of igniting gas that can shoot hundreds of metres into the air—or snake out horizontally, torching houses that would otherwise have been untouched.

All of this amounts to an extraordinary amount of energy being released every second of the fire’s existence.

A fire is regarded as unstoppable, even with the help of aerial bombardment, when it generates 3500–4000 kilowatts per metre. Firefighters know not to get in front of it; at best, they can attack its flanks, attempt to pinch it off, angle it in a particular direction.

The Black Saturday fires generated something in the vicinity of 80,000 kilowatts per metre. In the forest, where the DSE crew established their defence lines, that would have translated into temperatures anywhere between 1200 and 1500 degrees.