Kerry Girls (18 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

By 1 December, Strutt was recording ‘The girls are getting into good habits of cleanliness, order and tidiness and the school is well attended’. On Sunday 4 December, Hodgson reports ‘Emigrants washing clothes. They wash twice in the week, Tuesdays and Fridays.’

20

By 7 December, the girls were now ‘my girls’. His diary tells us on that day ‘My girls have become much more orderly and tidy under the constant steady pressure I keep up, against holes, rags, tatters, and dirt. They are pretty good as a body.’ That week Strutt had to stay up most of the night with Margaret Nelson (Clare) who had a severe epileptic fit, and he also delivered one of the married women passengers with a baby girl.

As well as all his other duties and responsibilities, Strutt was not above doing a bit of cooking if he felt it was called for. On Saturday 17 December as well as making a ‘wire grating for the fore hatch’ (to prevent unauthorised visits from male passengers) he also had ‘made a meat and sago pudding for my sick girls, which was highly approved’.

21

While Strutt was laying down the law on the standards he required, turning mattresses, fumigating bedding and keeping up pressure on the girls to attend the school, it was not all work and no play. In the evenings on deck, there was much singing and dancing. The girls were also allowed to bring up their ‘boxes’ from the hold, which always caused great excitement.

On Christmas Day 1849, the

Thomas Arbuthnot

was off the Cape of Good Hope. The captain handed out plum pudding and Strutt made them ‘five bucketfuls of punch, by way of cheering their spirits’.

22

This was his way of uplifting their depressed mood after the previous day:

Yesterday was devoted to keening, that is, to deploring their fate, old Ireland, and their friends and relations. Seven or eight would get together in a little circle, and keep up a most dismal howling … I dispersed one or two of these clubs and Mrs Murphy routed the rest by giving public notice that the keeners should have no pudding to-day, which proved an effectual remedy for their grief, so they fell to dancing and singing instead.

23

On 12 January Hodgson records that ‘One of the Emigrants, Mary Casey, deprived of speech’.

24

Mary Casey was one of the Listowel girls.

On Monday 4 February, they came into Sydney ‘cove’ and were immediately visited by the emigration agent, Mr Merriewether, the port doctor and the Anglican clergyman:

They were greatly pleased with the order and regularity of the ship, the fatness of my girls, and the cleanliness of their berths, tables, deck, pots and pans etc., and to do the poor wretches justice, they deserved the praise, for they had exerted themselves and worked like horses.

25

On Friday 8 February, the girls were transferred to a steamer to take them into port. Strutt walked at their head to the Hyde Park Barracks, referred to as ‘The Depot’. Not before there was ‘much weeping and wailing at leaving the ship’. ‘I stopped nearly all day at the Depot with them, got them settled as well as I could. They will now be visited by the Catholic clergy and nuns, for about a fortnight, confessed and persuaded to take the pledge. They will then be permitted to take situations’.

26

In October 1849, Strutt was the subject of a letter to the Land and Colonial Emigration Office from the Australian authorities. It concerned the difficulty the authorities were having in getting surgeon superintendents for the Irish Orphan Emigrants, at the current rate of 10

s

per emigrant landed alive. The letter reminded the Imperial Government of the extra responsibility involved with the Irish orphans and requested that the gratuity for each orphan landed alive should be 12

s

6

d

. In the case of the

Thomas Arbuthnot

, about to sail, ‘A gentleman named Strutt, who has been employed in our service, with much credit to himself, is one to which we think that the increased scale of remuneration might be very properly extended’.

27

The twenty-five Kenmare girls were next to depart on the

John Knox

, which left Plymouth on 6 December 1849 and, 140 days later, arrived at Port Jackson on 29 April 1850. Doctor Greenup was the surgeon superintendent. His wife, two sons and three daughters also travelled as cabin passengers. From the English Channel to the Cape of Good Hope, they reported experiencing nothing but ‘light baffling winds’.

28

They called at the Cape and stayed there eight days as they had trouble with water leaking from the casks on board. They set sail again on 10 March 1850 four days later they spoke to the ship

Earl Grey

on its way to Hobart with female convict prisoners. There were a total of 344 ‘Government Emigrants’, all registered as Irish, on the

John Knox,

including nineteen married couples with their children. There were two births during the voyage, an 18-year-old girl died on 28 January and four infants died later. While the Irish records show the names of twenty-five girls selected, we can account for only twenty-three arriving.

The

John Knox

had on board girls from Cork, Tipperary, Monaghan, Meath, Cavan and Down. The

Sydney Morning Herald

of 30 April 1850 reported that Captain Davidson’s ship had imported ‘30 tons pig iron, 9 tons chains, 176 tons salt, 2000 bushels rock salt, 3cwt sheet copper, 8 barrels oilman’s stores, 16 crates earthenware, 52 casks, 17 hogheads, 22 tierces soda ash, 10 bales candlewick, 203 barrels rosin, 81/4 barrels soap, 236 feet pitch pine, 1770 feet deals, 11 cases, 1 truss, Order’.

29

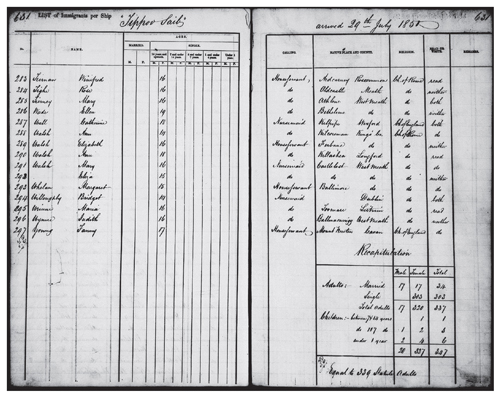

Tippoo Saib

logbook.

From the records we know that a number of the girls on the

John Knox

were placed in Sydney, and others, particularly the Kenmare girls, were moved on to Moreton Bay. It is significant to note that these were the girls who couldn’t read or write. They were also probably moved on north as they did not have any experience at housekeeping, seamstress or other occupations that the Sydney hires had.

Finally, seventeen girls left Listowel Workhouse and travelled initially to Dublin and on to Plymouth to leave on what was the final ‘female orphan’ ship to arrive in Sydney – the

Tippoo Saib.

This

1,022-ton ship with Captain Morphew sailed from Plymouth on 8 April 1850. The surgeon superintendent on board was Dr Church, who travelled with his wife and was allocated a cabin.

As well as the 297 Irish girls there were also a number of families, single women and ten children, six of them under the age of 10.

For the girls on the

Tippoo Saib

the novelty of their new environment soon wore off. While the food supplied was plentiful and of good quality, they suffered from the usual seasickness, partly the result of fear and trepidation of the unknown consequences of a rolling ship, high waves and a dark, cramped living accommodation.

Four months later, following brief stops for supplies and water in Teneriffe and Capetown, the

Tippoo Saib

was escorted into Sydney Harbour on 29 July 1850. Capt. Morphew’s report to the health authorities in Sydney stated that, of his passengers, one was suffering from lunacy, one had consumption, and another hysteria, Three had died on the voyage from ‘exhaustion, nervous irritation, and infection of the brain’.

30

The

Freeman’s Journal

(Sydney) recorded the

Tippoo Saib

arriving in Sydney on 8 April with ‘Passengers: Dr. Church and wife, Mr. Jackson and 249 emigrants’

31

Overall the Kerry girls on the four ships appear to have had reasonable voyages, were definitely well looked after, in so far as was possible on a crowded nineteenth-century ship. While we don’t have any records extant that tell us how the colonial authorities viewed the immigrant ships that brought the Kerry girls to Australia, we have mixed reports on other Irish ‘orphan’ ships:

Lady Peel

‘Likely to be useful in the colony and well behaved during the voyage’ Half the Surgeon’s gratuity withheld for inefficient performance of his duties.

Lady Kennaway:

Irish Orphan Ship. The girls behaved very well on the voyage and the Immigration remarks that very general approbation has been expressed with their character and capabilities.

Pemberton:

The ship arrived in a superior state of cleanliness; the arrangements are said to have been highly satisfactory, and the emigrants were grateful for their treatment. The efficiency of the surgeon, Dr. Sullivan, has since led to his receiving a colonial appointment.

New Liverpool:

An Irish orphan ship. Immigrants said to be totally uneducated and never to have been in any service. The girls from one Union were extremely refractory and troublesome.

1

Tenth General Report of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners, Appendix No. 7, p. 42.

2

Ibid

.

3

Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners Tenth Report, Appendix 1, p. 43.

4

Letter from W. Stanley, Secretary PLC to T.N. Reddington, Dublin Castle, quoted in Trevor McClaughlin,

Barefoot & Pregnant?

(Melbourne, 2001), p. 9.

5

Ibid.

6

Thomas Keneally, T

he Great Famine and Australia

, p. 553.

7

South Australian Register

(Adelaide, SA 1839–1900), 12 September 1849, p. 2. Web. 28 August 2013.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news

, p. 2.

8

Ibid.

9

Charles Edward Strutt, Journal, October 1849–May 1850 …, State Library of Victoria, Manuscripts Collection, MS 8345. Strutt was on board the emigrant ships

St Vincent

, London to Sydney, and

Thomas Arbuthnot

, London to Sydney and return.

10

Strutt, Journal, p. 3.

11

Ibid., Tuesday 23 October 1849, p. 61.

12

Ibid., Saturday 27 October 1849, p. 61.

13

D.B. Waterson, ‘Hodgson, Sir Arthur (1818–1902),

Australian Dictionary of Biography

, Australian National University,

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hodgson-sir-arthur-1155/text5963

, accessed 15 July 2013.

14

Ibid., Thursday 1 November 1849.

15

Hodgson, 4 November 1849.

16

Ibid.

17

Strutt, Journal, 11 November 1849, p. 63.

18

Charleville Times

, Brisbane, 24 October 1947, p.18.

19

‘Passing of a Pioneer’,

Brisbane Courier

(Qld 1864–1933), 1 April 1916, p. 12, viewed 19 November, 2013,

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20100448

20

Hodgson, 4 December 1849.

21

Ibid., 17 December 1849, p. 63.

22

Ibid., 25 December 1849, p. 66.

23

Strutt, Journal, Tuesday 25 December 1849, p. 67.

24

Hodgson, Saturday 12 January 1849.

25

Strutt, Journal, Monday 4 February 1850, p. 70.

26

Strutt, Journal, Friday 8

February 1850, p. 71.

27

Sydney Morning Herald

(NSW: 1842–1954), 27 July 1850, p. 3, viewed 19 September 2013,

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12919795.

28

Sydney Morning Herald

(NSW: 1842–1954), 30 April 1850, p. 2, viewed 18 September 2013,

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1511705.

29

Sydney Morning Herald

, 30 April 1850, p. 2.

30

Research by Peter Noone, descendant of Catherine Noone’s brother, Martin Noon. November 2012.

http://www.irishfaminememorial.org/media/Noone_Catherine.pdf

.

31

‘Shipping Intelligence,’

Freeman’s Journal

(Sydney, NSW: 1850–1932), 1 August 1850, p. 6, viewed 19 September, 2013,

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115767258.

WORKING LIFE AND MARRIAGE IN AUSTRALIA

W

HEN THE FIRST

of the ships taking the Irish orphans to Australia arrived there in September 1849, the orphans arrived in a country that had only been settled by Europeans sixty-one years previously. Before 1788, Australia was populated by about 300,000 aborigines. These nomadic people had inhabited the world’s oldest continent for more than 10,000 years. The aborigines reaction to the arrival of settlers was varied and sometimes hostile, particularly when the colonisers’ occupation led to destruction of lands and food resources, in turn leading to starvation, demoralisation and eventually annihilation of their way of life. In 1846 the British Government passed a law that new land leases should not deprive the indigenous people of their rights to hunt over land fenced or cultivated, but on the ground these laws were mostly ignored. A widespread economic depression was experienced by the new settlers between 1841 and 1846 because of drought and the collapse in wool prices. Thousands were bankrupted and there was mass unemployment. However, by 1849 the economy had improved and the colonial government passed a law that would give squatters fourteen-year leases to their runs. This law gave the squatter temporary security and enabled him and his family to clear their land, plant and stock their selections and make plans for the future.