Kerry Girls (14 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

T

HE ONLY INFORMATION

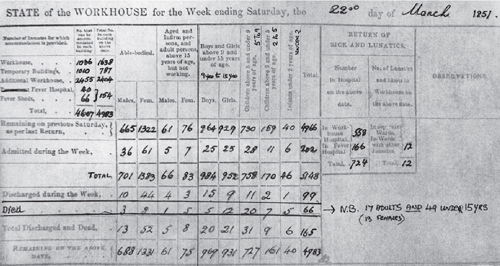

available to us, from workhouse records, on the background of each individual girl is a name and, in a few cases, the electoral area from which the girl had been registered when they were selected for the emigration process. However, as recorded in the example below,

1

the age groups and the capacity of each inmate for work were included, as were the number admitted each week, the number already there and the number who died or were discharged. Also included were the auxiliary workhouses and fever hospital and the number of ‘lunatics and idiots’ in the workhouse at each weekly date.

While precise records were kept of all expenditure and the type and amount of food consumed, there is very little else in the way of identities or pen pictures of any of the inmates, available to us.

It is only if an inmate caused a row or disturbance that their name would get a mention. There is a case in Kenmare where Mary Downing, Mary O’Sullivan Stretton, Abby Coughlan and Mary McCarthy are named in the minutes as they caused ‘a disturbance’ and were sentenced to a month in gaol in Tralee with hard labour (see Chapter 5). We also have reports in Killarney of an allegation that ‘a pauper named Mary Sullivan’ had accused another pauper named Jude Spillane of ‘attempts to induce her to become a protestant’.

2

But other than these few individuals named in the Minutes of Board of Guardian meetings, we have no records of inmates, when they entered or how long they stayed in each workhouse.

Listowel Workhouse weekly returns, 22 March 1851. It records that sixty-six people died this week, seventeen adults and forty-nine under the age of 15 years.

We have the names and electoral districts of the first lot of girls from Listowel who travelled on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

, and we also have the names and electoral districts of the Kenmare girls who travelled on the

John Knox

. The principal reason for recording the electoral districts, in the case of Kenmare at any rate, was to note which areas were chargeable for the expenses incurred in the emigration process, rather than to keep a precise record of who left and how they left.

However, very precise records were kept in Sydney on the ship’s arrival. When the

Thomas Arbuthnot

arrived on 3 February 1850, the

John Knox

on the 29 April 1850 and the

Tippoo Saib

on the 29 July 1850, the girls’ names, ages and their home addresses were taken, as well as the workhouses that they originated from. Their parents’ Christian names, their religion and their ability (or not) to read and write were also noted. From these records, we are able to match our lists of those who departed to those who arrived.

To the uninitiated, some of these arrival records make no sense. It helps that the researcher speaks and understands the Kerry accent! So when ‘Margaret Ginnea’ arrived in Sydney on the

Tippoo Saib

and declared she was from ‘Stow’, we can match her up with ‘Margaret Ginniew’ who is on the Listowel Workhouse list. Margaret would have told the clerk in Sydney who was taking down her details that she was from ‘Shtow’, which we who are used to the local idiom understand plainly as ‘Listowel’. To add to the confusion, for some reason anyone in North Kerry who was called McKenna was also called ‘Ginnea’. Catherine Kennedy gave her address as ‘Brandon Bay’ and Bridget Moore as ‘Cashel’, these were respectively from Brandon and Castlegregory. Catherine Manning of ‘Kilmoyle’ and Ellen McCarthy of ‘Kilmajer’ we can immediately deduct are respectively from Templenoe, Kenmare and Kenmare itself.

The arrival records state the ages of the girls ranged from 14 to 20 years of age. However, we can see that these ages are very inaccurate when we compare the actual church baptismal certificates of those girls whom we can trace. Birthdays and ages were of very little significance in the nineteenth century. The system of registration of births in Ireland at that time was that the individual was responsible for registering the birth. The authorities, as an ‘encouragement’ to do this, would impose a hefty monetary fine on the individual who didn’t comply with the law. So a birth registration might take some time to be recorded and the exact day, and even year and place might not be correct when it was finally registered. In quite of a lot of cases, particularly in rural, inaccessible country, the birth was never registered. These inaccurate birth dates have persisted through the follow-on records in Australia, resulting in wildly differing birth dates given on marriage, children’s baptisms and death certificates. There would not have been any subterfuge or dishonesty intended. When genealogists are conducting research now in Ireland for nineteenth-century ancestors, it is a recognised fact that ‘the actual date of birth is almost always well before the one reported, sometimes by as much as fifteen years’.

3

The vast majority of the girls were probably aged 16 and 17, even though seven girls stated on arrival that they were 14. They were Mary Healy (Killarney), Catherine McCarthy (Killarney), Mary Kearney (Dingle), Margaret Foley (Kilgarvan), Ellen Lovett (Kenmare), Johanna Sullivan (Listowel) and Johanna Donoghue (Killarney), who died at sea while on the

Elgin

, which was bound for South Australia.

It is interesting to note that four of these five girls were recorded as being able to both read and write. This is probably because the younger they were, the more opportunity they would have had of attending the new National Schools which were built from the early 1840s, or they may have attended the hedge schools prior to entry to the workhouse. Of the older girls, close to sixty

4

of the girls could neither read nor write. As most of the girls were also from country areas, Irish would have been their first language, but even if not able to read or write in English they would have understood the language for the most part and have started to speak it.

Of the 117 Kerry girls, 112 were recorded as ‘Church of Rome’. Five of the girls gave their religion as Church of England; four of these were from Listowel and one from Kenmare. While researching the background to the girls, each girl was matched with the church records of baptisms in Kerry, through her name, parents’ details and parish, if known. This was quite frustrating, as in a number of cases the girls’ details did not correspond with the parents’ names they had given. While we know that a number of the girls were orphans in the accepted sense, i.e. with both parents dead, in any Union workhouse there would also be a number of girls born outside marriage or certainly baptised before their parents married. These girls would not have necessarily known the names of their fathers. Yet every girl gives the name of both a father and a mother.

Illegitimacy was a taboo subject in nineteenth-century Ireland. Moral, financial and social approbation were all levied against the unmarried mother. She had very few rights and all the responsibilities. The Poor Law Act (1838) placed the sole responsibility for supporting children born outside marriage on the mother, and put the father under no legal obligation to his extra-marital child. Many single mothers had no option but to take refuge in workhouses. Ratepayers who funded the workhouses resented supporting these women and children and an Irish Poor Law Amendment Act was passed in 1862.

5

It empowered Boards of Guardians to recover from a presumed father the cost of maintaining his illegitimate child on the Poor Rates, after the mother had made a sworn statement, supported by corroborative evidence, before petty sessions. The new laws gave no power to the mother to sue the father, and once she left the workhouse the liability of the father ended.

6

The separation of the moral and respectable women from geographically mobile and subsistent women was essential practice at this time, as it was believed by middle-class men that female immorality was contagious to other women.

7

In Kerry, different baptismal standards applied in different areas. Baptismal records in the early 1800s were written in longhand in Latin. While generally speaking the name of the admitted father was not included, some priests might write it in or append a side note as

illegitimus

or

pater ignotum

(father unknown). In most cases there would not be an admitted father. In Ballyduff/Causeway between September 1824 and September 1828 the priests who ministered in this area appear to have baptised those born outside marriage by registering boys with the name of Jasper and likewise the girls as Winifred. There is a total of eighteen boys baptised as Jasper and seventeen girls as Winifred during these four years. In February and March 1828 all seven baptisms in the area are called one or other of these names! As these names are never again recorded in this or indeed any other area in Kerry, we will have to presume that the parents (with the exception of Winifred’s) didn’t use them as everyday Christian names. In these cases of Ballyduff/Causeway there is both a mother and father’s surname name on all of the baptismal records, and it is interesting to note that the children born all bore the father’s surname.

Among the 117 Kerry girls on the Earl Grey Scheme, there are a number of respectable and well-behaved girls who had been born outside marriage, most of whom would prefer this fact not to be known. They would have wished to start in their new world without any perceived stain and they cannot be blamed for this. Neither could they be blamed for the sins of their parents and there was every likelihood that they would become ‘active and useful members of a society which is in a state of healthy progress’.

8

Of the nineteen Dingle girls, we know that twelve declared that both parents were dead, three of the fathers were alive ‘in Dingle’ and five of the mothers. Of those who were still alive, Mary Barry declared that her father’s residence was ‘unknown’ and her mother lived in Castlegregory. Mary Griffin, whose baptismal certificate states that she is from Ballynabuck, Ballyferritter, says that her mother is ‘living near Dingle’ which more than likely meant that she was still at home in Ballyferritter. We would have to assume that at least some of those ‘alive’ were still in the workhouse in Dingle. The Moriarty sisters – Catherine (17) and Mary (16) – whose parents were both dead, hailed from Dingle town.

The geographic area of Castlegregory and Brandon, whose population is now a quarter of what it was before the Famine, both coastal areas, suffered more than most during the Famine. The journey to obtain food and/or shelter, initially to Tralee and later to Dingle over unmade roads through mountain passes, was one of unimaginable hardship. Mary Barry, Julia Harrington, Bridget Moore and Catherine Kennedy, with their families, had to trudge to the workhouse, in a cold, hungry, unclothed and shoeless state, the long miles without any guarantee of getting help at the end.

It has not been possible to trace a number of the Dingle girls, principally those who were baptised in the town, as the extant records are illegible from March 1828 to April 1833, a period when most of the girls concerned were baptised. At a future date, with newer technology, it may be possible to retrieve these important records.

Mary Griffin

Mary Griffin was born 16 March 1831 in the parish of Ballynabuck in Ballyferriter, Dingle to John Griffin and Mary Sullivan. There were at least five more children recorded in the Baptismal registers:

1. John Griffin – Baptised 3 march 1829

2. Mary Griffin – Baptised 16 march 1831

3. Maurice Griffin – Baptised 31 March 1834

4. ? Griffin – Baptised 11 September 1836

5. Johanna Griffin – Baptised 14 September 1839

6. Catherine Griffin – Baptised 13 April 1843

She was one of twenty girls selected from Dingle Workhouse to travel to Australia on the Earl Grey Scheme. On arrival, her records tell us that ‘her mother was living near Dingle’, and that she ‘cannot read or write’. To be fair to Mary, Irish would have been her first and perhaps only language and it may be that she could not read or write English. Her age is correctly given as 19.

We would presume that her father was dead by autumn 1849, when she was selected. There is no evidence now available that her siblings were alive then, perhaps also in the workhouse, or that they had died from hunger or from one of the many fevers and diseases that swept through the population.

Mary was one of the lucky girls; she was taken by Surgeon Charles Strutt with 108 others on a journey into the interior of New South Wales where Strutt carefully vetted all the applicants for servants. If he felt that they would not get a good home and be treated properly, he had no compunction if refusing employers or indeed removing the girls to better employers.

Mary’s great-great-grandson Nathan Brown tells us:

Mary Griffin was employed by landowner William Grogan of Sawyer’s Flats, near Yass (West of the Burrowa river; east of Sawyer’s Creek; south of Hassall’s Creek; north of the colony’s boundary line) for one year on £8. The land was roughly 9,700 acres and was estimated to have the capability of grazing 400.

Less than one year later, Mary married William Dixon [Dickson, Dixson] (also of Sawyer’s Flats) on the 2nd March, 1851 at St. Augustine’s Roman Catholic Church, Yass.

Mary Griffin and William Dixon had two children, Ellen Dixon who was born about 1852 in Yass and died on 4th May in Rye Park, New South Wales. She married David Percival in 1872 at Binalong, New South Wales. David was unusually for the times, a native Australian, born in Sydney in 1845, the son of William Ambrose Percival and Anne Semple. David died at his home in Campbell St., on 24 December 1933 having been stricken down two weeks earlier by a paralytic stroke. He was buried on Christmas Day. Ellen Dixon and David Percival had fourteen children.

While all the ‘orphans’ experienced loneliness, those who settled in the areas around Yass were probably the most fortunate. A number of Mary’s shipmates from the

Thomas Arbuthnot

were settled there, including a number of the Dingle girls. The main route from Sydney to Melbourne passed through the town, so it was an important place of commerce and was the centre of widespread Catholic and Anglican parishes. Yass was the place where the families from the outlying areas got together for the big events in life – baptisms, marriages and funerals in the local churches. The settlers in the outlying bush districts also came to Yass a couple of times a year for their supplies.