Kate Berridge (3 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Bertin is often credited as the creator of haute couture, and at the peak of her power she turned Marie Antoinette into the costliest and most widely copied clothes horse in the world. Long before she acquired her own legendary showroom she served her apprenticeship at Trait Galant. And before the ravishingly pretty young Jeanne Bécu became Madame Du Barry and the mistress of Louis XV, with perks that turned her life into a perpetual shopping trip, that was where she trimmed hats and tended customers. Madame Du Barryâshown languid, long-necked and delectable on a daybedâwas one of Curtius's earliest and most popular figures on public display. One of the wax portraits which Marie brought with her to England, this model can still be seen. When it was first shown, the sex life of the King was a topic of great interest, and there was a particular frisson in being able to get up close to a recumbent model of his mistress and indulge in salacious speculation in earshot but not hearing of her delicate waxen lobes.

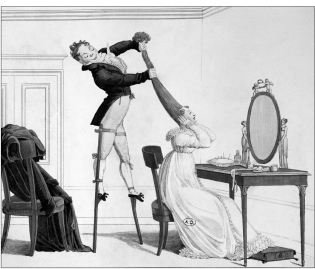

After the rustic charms of Berne, a city of clogs and lederhosen and women with plaits, Marie as a little girl was plunged into a society where noble women wore wide hooped-skirts called panniers, towering wigs, and shoes designed not to be walked in. Madame de La Tour du Pin (born Henrietta-Lucy Dillon) whose journal spanning the demise of Louis XVI to the restoration of the monarchy is a brilliantly illuminating social history of this period, recalled ânarrow heels, three inches high, which held the foot in a similar position to when standing on tiptoe to reach the highest shelf in the library'. How strange these upper-class constrictions of high heels, high hair and

heavy skirts must have seemed to the gimlet-eyed child, whose keen powers of observation took in every detail. The restrictions of dress underscored the privileges of aristocratic indolence, and from early childhood Marie must have quickly grasped the gulf between classes as she contrasted the exotic immobility of the grand dames carried in sedan chairs or conveyed in fine carriages that came and went from the aristocratic enclave that was where de Conti first housed his protégée in Paris to the heaving bustle of street life and the coarse realities of the crowd that she and her mother had to brave as they familiarized themselves with the city.

For a curious child it was probably hard not to stare at the vivid vermilion cheeks, painted in garish circles, that were another affectation of aristocratic women. The more refined the woman, the more artificial the look: a natural blush, with associations of the flush of boudoir exertion, was suspect, and a lack of cosmetic colouringâtoo little make-upâcould get a woman labelled a courtesan. The aristocrats lived in a world far removed from the mêlée of the masses, yet it was increasingly a world aped by the rising ranks of the middle classes. Advertisers cottoned on to aspiration as a selling point, as is evident from the marketing of such products as Rouge de la Reine and Savonette de la Cour.

Small-print advertisements from the papers of the day are like a spyhole on the preoccupations of the Paris that Marie knew. Columns are crammed with endless products to enhance the human canvasâpaint and pomade, teeth-whitening and-strengthening products, hair dyes, wig-adhesives. Bear grease was regarded as a luxury hair conditionerâone brand was advertised as being made in America âby the savages of Louisiana'. The importance attached to appearances was remarked upon by the American lawyer and man of letters Gouverneur Morris, who noted, âThey know a wit by his snuffbox, a man of taste by his bow, and a statesman by the cut of his coat.'

The importance attached to appearances undermined the former deference, and, as the force of fashion grew, it was as if a veneer of superficiality was being laid over the old order. Indicative of this was the way that feathersâtraditionally associated with ceremonial dress and nodding plumes that commanded respectâbecame fashion accessories, and feather shops flourished. However, the effect was not

always what the wearers desired, and Mercier described how a sudden downpour lent âerstwhile exquisites the appearance of wet hens'.

Whereas rank used to be evident from differences in appearance, now it was harder to assess, as the collective love affair with hairdressing filtered down to the lowlier ranks of society. Mercier wrote, âThe rage for hairdressing has become universal in every class. Shopboys, bailiffs, notaries, clerks, servants, cooks and scullions all wear tails and queues, and the perfume of various essences and of amber-scented powder assails you from the general shop as well as from the oiled and scented dandy.' Fashion was not merely frivolous: it was subversive. Self-invention, emulation and imitation were starting to bring a dangerous ambiguity to appearances. The proliferation of affordable clothes meant that people were not always quite what they seemed. A buoyant market for second-hand clothes operated from both permanent premises and market stalls. The Place de Grève, when not drawing crowds for public executions, became a colourful communal changing room, with rows of stalls putting the finery of respectable society within reach of all. Mercier writes, âHere the wife of a clerk haggles for a grand dress worn by the dead wife of a judge; there a prostitute tries on the lace cap of a great lady's lady-in-waiting.' Demand did not always match supply, spawning a singular form of daylight robbery in which women assaulted well-dressed children and stripped them of their finery, replacing it with inferior garb. Mercier again: âThese women have lollipops and children's clothes already prepared but of small value; they have an eye for the best-dressed children and in a turn of the wrist possess themselves of good cloth, or silk or silver buckles, and substitute coarse rags.' A lacemaker accused of this unusual form of asset-stripping was whipped, branded and put in the pillory under a large sign saying âDespoiler of Children'. This public humiliation was but the preliminary punishment before she was sent to La Salpêtrière prison for nine years.

Deception of dress also happened at the other end of the scale. Madame Roland relates how on one occasion she ventured out in her maid's clothes âlike a real peasant girl'. More used to the comfort of the carriage, she found the gutters and mud a shockâand even more so the experience of âgetting pushed by people who would have made way for me if they had seen me in my fine clothes'. Much more

famous are the clichéd images of Marie Antoinette dressed down as a dairymaid in an interior designer's dream of a dairyâall Delft tiles and clean cowsâengaged in an extravagant pastoral fantasy. In fact the only time she assumed the role of innocent rustic was on the stage, as part of Versailles' version of amateur dramatics. In reality, virtually from the moment she became queen in 1774, when Marie was a girl of thirteen, the people of Paris were the sheep following every new style that Marie Antoinette adopted. So great was the desire to copy the Queen that one night, when she appeared in her box at the opera displaying a new hairstyle for the first time in public, the resulting crush to get a closer look gave a new seriousness to the term âfashion victim'. Léonard, her hairdresser, was unashamed in the pleasure he took from this incident âPeople in the pit crushed one another in their endeavour to see this masterpiece. Three arms were dislocated, two ribs broken, three feet crushedâin short, my triumph was complete.' In her memoirs, Marie relates how the Queen, aware of this mimicry of her every accessory, once played a joke on the public: âIn the zenith of her splendour, she would often smile at the servile imitation of her dress which was displayed by ladies of the court, and those even of the lower class; and to illustrate this mania, the Queen once went to the opera with radishes in her headdress; but the sarcasm was understood, and such ornaments were never adopted.'

Whether through dressing up or dressing down, the confusion of rank became a source of concern. The author of an anonymous tract first published in Montpellier proposed a practical solution to this new social problem. He advocated a legal requirement for servantsâmale or femaleâto wear a clearly visible badge on their clothes,

for nothing is more impertinent than to see a cook or a valet don an outfit trimmed with braid or lace, strap on a sword and insinuate himself among the finest company in promenades. Or to see a chambermaid artfully dressed as her mistress, or to find domestic servants of any kind decked out like gentle people. All that is revoltingâ¦One should be able to pick them out by a badge indicating their estate and making it impossible to confuse them with anyone else.

That appearances could be deceptive seemed to capture the collective imagination of Paris. Embodying this theme was a charismatic

celebrity called the Chevalier D'Eon, whom Marie describes as âone of the most remarkable individuals, of those in the habit of meeting at her uncle's house'. He was the subject of intense speculation, rumours and gossip, and there are many different accounts of his life. One version has it that, a man of noble birth with a distinguished military career, the Chevalier was sent on a delicate diplomatic mission to England, which went badly wrong. In order to extricate himself and to escape from his enemies without leaving a trail, he adopted the brilliant ruse of pretending to be a woman. On his return to France in 1777 he continued to wear women's clothes, and reports circulated that the Chevalier was to be found stepping out in high society in the latest fashionsâmodified to conceal the throat, to complete the impression of feminine grace. One account claims that the Queen took an interest in him, and sent him to be clothed by Rose Bertin. What the sixteen-year-old Marie made of this intriguing character she does not say, but her version of his circumstances is slightly different. She has it that the Chevalier had in fact been born a girl, but to prevent the disappointment of her father had been brought up as a boy. However, she concedes that âthere was something about D'Eon which always appeared to convey an air of mystery.' The uncertain status of the cross-dressing Chevalier and the way he captured the public imagination seem to exemplify the unstable boundaries and fluidity that were such important trends in the Paris of Marie's youth.

Another of the important forces weakening old structures was the growing power of the increasingly conspicuous middle class. The desire to make a statement was expressed pretty much the same way then as now, for in pre-Revolutionary Paris too one's vehicle was not merely an A-to-B device, but a status symbol. As Mercier said, âA carriage is the goal of any man that sets out on the unclean road to riches: the first stroke of luck buys him a cabriolet, which he drives himself; the next a

coupé

; and the third step is marked by a carriage, and the final triumph is a second conveyance for his wife.'

Plus ça change

.

Things that had previously been available only to the rich minority materialized in a dazzling variety of affordable imitations. The famous wallpaper manufacturer Réveillon offered a cut-price slice of pretension with designs imitating the tapestries that hung in the

palaces of the wealthy, and for those who wanted an instant library but without the expense of fine volumes, or the effort of having to read, instant bibliophile credibility could be had by installing imitation book spines. Stucco stood in for marble and porcelain for gold, and increasingly it was hard to spot the authentically aristocratic from the convincing fake, whether in interior design or in people.

From the humblest servant with a simple hand mirror to the elaborate rococo looking glasses in the homes of wealthy merchants, a new self-awareness tipped into an epidemic of vanity. Whereas the middle classes had once looked up to monarchy and those in positions of power, now it was their own reflection that concerned them. They could not stop looking at themselves, and self-definition in public was a preoccupation bordering on obsession.

Mirroring increased public access to a vast range of clothes, accessories, fixtures and fittings was the democratization of culture. Whereas formerly culture had been largely shaped from above, and functioned as an important part of the apparatus of elitism by means of which an absolute monarchy emphasized its power, now the

cultural framework was changing. A greater range of people were pursuing similar cultural interests, whether a shared newspaper in a café, a visit to the Salon, or a trip to the waxworks.

Further, in much the same way that what had once been luxury goods became commonplace items in many homes, this period sees the advent of the household-name celebrity figures, often self-made, whose fame was as real in aristocratic circles as it was in the homes of artisans and tradesmen. Social mobility brought with it a new possibility of prominence in public life. While not precisely the sons of the butcher, the baker and the candlestick-maker, Rousseau and Beaumarchais (the sons of watchmakers), Diderot (the son of a cutler), and Mercier (the son of an artisan) all became well-known figures. This marked a shift whereby the grounds for fame became increasingly hard to distinguish from familiarity to the wider public. This phenomenon anticipates contemporary culture, where often a celebrity's claim to fame is as tenuous as being photographed regularly, or being seen but not necessarily read, watched or heard. In the Paris of Marie's youth it was increasingly possible to be famous for being famous.