Jungle of Snakes (26 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

However, mobility did please senior commanders because of the reduction in CAP marine casualties. Also, the mobile CAP posed

a new challenge for the enemy. As one CAP leader explained, the marine mobility kept the Viet Cong “guessing”; they “don’t

like to come after you unless they’ve had a chance to get set and do some planning.”

18

So as the war continued, the marines proceeded with a modified but still unique experiment in counterinsurgency. In 1967

one typical dedicated CAP marine responded to an interviewer’s query about the effectiveness of the CAP: “We’ve got some real

good PFs here and the CAP is what’s going to help win this war.”

19

THEN AND THEREAFTER it was left to a handful of military specialists to assess the validity of the marine strategy. At the

time, regardless of what the marines accomplished by pursuing their vision of pacification, the very fact that they were trying

infuriated many among the army high command. General Harry W. O. Kinnard, the commander of the first army division to arrive

in Vietnam, the famous First Cavalry Division, Airmobile, later pronounced himself “absolutely disgusted” with the marine

approach. Major General William E. Depuy, Westmoreland’s chief of operations and commander of the army’s First Infantry Division,

concurred: “The Marines came in and just sat down and didn’t do anything. They were involved in counterinsurgency of the deliberate,

mild sort.”

20

Had Depuy read the 1940 edition of the

Small Wars Manual

, with its emphasis on applying the least force to achieve decisive results while exhibiting “tolerance, sympathy, and kindness”

toward the civilian population, he might have understood better what the marines were about.”

21

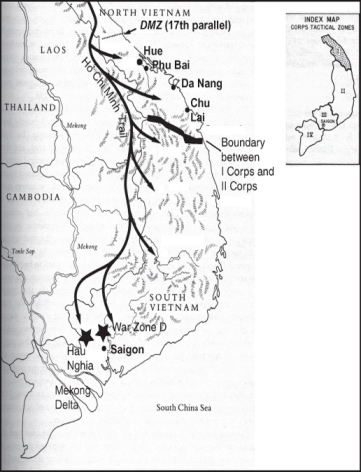

Instead, MACV focused on the Communist main-force threat, and it was formidable. In 1966, an entire North Viet namese division

had invaded across the demilitarized zone separating North and South Vietnam. The invasion compelled Marine General Walt to

reposition about half the marines who had been assigned to pacification duties. The statistical analysis so dearly loved by

Pentagon planners highlighted the challenge. In the middle of 1966, in I Corps the enemy had 17,000 North Viet namese regulars

(NVA); 8,000 Viet Cong armed, equipped, and trained for conventional combat; and 27,500 guerrillas. Each month an estimated

2,600 regulars infiltrated across the demilitarized zone and the Viet Cong gained 2,000 recruits. Against such numbers, pacification

could make little progress. Clearly, the solution had to start with curtailing the enemy’s ability to reinforce and recruit.

Only then could pacification make progress, and even then it would take an estimated fifty-one months to destroy the Communist

infrastructure. The somewhat more optimistic marine assessment recognized that until the NVA threat was gone, the marine enclaves

would be unable to link up, the oil spots unable to merge. Then another twenty months would be needed to establish effective

government control and this presumed improved, increasingly effective South Viet namese forces.

Herein lay another huge problem. Until the Tet Offensive, the marines and regular South Viet namese forces had shielded, albeit

imperfectly, the villages from the enemy main forces. But the government forces, both the militia and the civil officials,

were unable to convert the villagers to the government side. According to decisions made in October 1966, the South Viet namese

were supposed to undertake the balance of the pacification effort throughout Vietnam. This effort faltered for numerous reasons,

including corruption and ineptitude, with the results ranging from ineffective to counterproductive. Even had the existing

South Vietnamese forces been effective, there were not enough of them. The village-based popular Forces and National Police

were keys to an effective pacification program. However, casualties and desertion, and a nationwide competition for qualified

recruits, left both forces badly under strength and filled with marginal manpower. In I Corps, American planners estimated

that another 18,000 militia were required along with twice the number of available National Police. The Rural Development

effort was likewise weak, with only 13 operational teams when planning called for 111. At that rate, marine analysts estimated

it would take twenty years to complete the government’s planned Rural Development policy.

The British in Malaya had understood that pacification was a long, drawn-out process. They made an open-ended commitment to

see the job through. If the Combined Action Program was to succeed, it required a similar commitment. As the Vietnamese official

in Le My, the first village to experience the marine version of pacification, had said to General Kru-lak, “All of this has

meaning only if you are going to stay. Are you going to stay?”

22

Westmoreland’s Way of War

THE MARINE CORPS STRATEGY TO PACIFY I Corps confronted opposition both from senior South Viet namese leaders and from the

head of MACV, General William C. Westmoreland. For the South Vietnamese leaders, pride and politics played a role. They did

not want the marines accomplishing something that they could not do. They also wanted their own fingers in what they sensed

could become a very lucrative pacification pie. Somewhat oblivious to these underlying currents, Westmoreland had reached

the plausible conclusion that because the South Vietnamese spoke the language and presumably understood the local culture

they were better suited for pacification than Americans. The “Other War” was no doubt important, but Westmoreland’s every

instinct informed him that the path to victory lay in defeating the Communist regular units in a big-unit war of attrition.

The fifty-year-old Westmoreland had seemed marked for high command ever since his West Point days, when he was appointed first

captain of cadets and won the coveted Pershing Trophy for leadership. In World War II he achieved a distinguished record as

commander of an artillery battalion during the North African Campaign and later as chief of staff for the Ninth Infantry Division.

His qualities impressed the paratroop general James Gavin, who invited Westmoreland to transfer to the airborne forces after

the war. Westmoreland performed very well in a succession of prestigious postings, including commander of the elite 101st

Airborne Division and superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, where he introduced counterinsurgency into the West Point

curriculum. In keeping with the military’s burgeoning emphasis on scientific management, he also completed a course of study

at the Harvard Business School.

Before assuming command in Vietnam, Westmoreland had traveled to Malaya to study how the British had dealt with their insurgency.

Robert Thompson escorted him. Westmoreland found the trip interesting but not particularly relevant. He concluded that there

were simply too many differences: the British had commanded both their own and the entire civilian military and government

apparatus, the ethnic Chinese insurgents were easily distinguished from the population, and there were no cross-border sanctuaries

for the Malayan insurgents. Westmoreland decided that “we could borrow little outright from the British experience.”

1

As he gazed across Vietnam’s strategic chessboard, Westmoreland saw a valuable fighting asset, the marines, hunkered down

within their enclaves. In Westmoreland’s mind this represented waste. Indicative of his attitude was his reaction to a marine

report regarding promising results from a civic action program called Country Fairs. Westmoreland responded that this was

all well and good, but he did not want any dissipation of American strength “to the detriment of our primary responsibility

for destroying mainforce enemy units.”

2

He made it abundantly clear that he wanted the marines out searching for the main-force Communist units in order to bring

them to battle. Henceforth the counterinsurgency effort took place against a background of conventional combat between American

and Communist main-force units, most notably including North Viet namese regulars.

As the dominant military partner in this effort, the U.S. army acted according to its limited-war doctrine, which called for

rapid restoration of peace achieved by decisive combat with the enemy. This doctrine played to the army’s strengths: its massive

firepower and tremendous mobility conferred by a heli copter armada. The army would conduct a war of attrition utilizing the

weapons and tactics designed to defeat the Soviet Union in a conventional conflict. It would grind down the Communists until

they gave up. The “Other War,” the counterinsurgency campaign, would always be subordinate to this war of attrition. When

asked at a press conference what was the answer to insurgency, Westmoreland gave a one-word reply: “Firepower.”

3

THE SO-CALLED BIG-UNIT war hugely complicated the counterinsurgency without changing some of its basic dynamics. While the

U.S. military provided a security shield, U.S. civilian agencies continued working to implement social and economic reforms

in order to win popular support for the Saigon government. This popular support would both legitimize the government, thus

depriving the Communists of a crucial plank in their antigovernment rhetoric, and delegitimize the guerrillas.

At the same time, the U.S. Army participated in pacification. Its involvement included civil affairs, which were efforts to

improve rural living conditions, and direct provision of village security, a task absorbing only a small portion of the army’s

combat strength. In spite of Westmoreland’s initial skepticism, the army particularly touted its involvement in Country Fair

operations that combined civic affairs projects with cordon-and-search operations. The intent was to tackle one village at

a time, root out the Viet Cong infrastructure, and build Popular support for the government.

Thirteen miles north of Saigon was the village of Tan Phuoc Khanh. Because of its strategic location in the notorious and

Communist-dominated War Zone D, the region had been the focus of numerous allied military campaigns. In June 1966 they tried

again when a joint force of South Vietnamese and American regulars entered Tan Phuoc Khanh to conduct a Country Fair. Over

succeeding days the Americans provided security while Vietnamese teams organized local elections, conducted a census, and

began small construction projects. Meanwhile, a joint task force spent three days trying to uncover Viet Cong agents. Given

that the Viet Cong had spent years establishing themselves deep inside Tan Phuoc Khanh, this was far too little time. The

regulars departed—the villagers missed the Americans, who had actually provided real albeit too-brief security, and were happy

to see the backs of the South Vietnamese soldiers, who had preyed on them—and the local militia took over security duties.

Sensing weakness, the Communists began probing. In November 1967, some seventeen months after the Country Fair, a Viet Cong

company overran Tan Phuoc Khanh’s central watchtower. The next month a hamlet chief resigned for fear of his life. At year’s

end two American field evaluators visited the village and correctly concluded that the official rating that labeled Tan Phuoc

Khanh “secure” was wrong.

The experience at Tan Phuoc Khanh was typical of the U.S. Army’s attitude toward pacification. A Country Fair operation might

attract good publicity with its army band entertaining the villagers and civil affairs personnel running a diverting lottery.

A barbecue fed people for a day. A medical team could provide inoculations lasting much longer. None of these things harmed

the war effort. But by the same token, none of them was anything more than a palliative that accomplished little toward establishing

lasting security or forging stronger bonds between rural villagers and their remote government in Saigon.

The Rise of Robert Komer

For all the blame that American planners heaped upon the South Vietnamese for their faltering pacification efforts, a hard

look in the mirror showed significant American failures as well. The inability of U.S. military and civilian agencies to pull

in harness impeded significant progress. After years of fighting an insurgency, many American military and civilian strategists

appreciated, albeit with varying degrees of clarity, the importance of pacification. Some also perceived that existing programs

were truly inefficient. While the unwillingness of a rural villager to support the government involved a host of difficult,

sometimes incomprehensible cultural issues, management and organizational issues were two things Americans understood. They

could be tackled by improved efficiency, re-organization, and the application of more resources—in other words, by the application

of sound management practices—or so an influential group of bureaucrats claimed.

An ex-CIA analyst named Robert Komer gained the ear of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and had himself appointed to Saigon

to serve as chief of pacification. Komer was nothing if not energetic. His ability to force his solutions on an unresponsive

bureaucracy earned the hot-tempered Komer the nickname “Blowtorch.” In 1967, he oversaw the hatching of a centralized pacification

program called Civil Operation and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS). President Johnson invested high hopes in the

program, knowing that CORDS had far more resources—funds, personnel, and equipment—than previous efforts. He recalled Komer’s

prediction that after one year of operation there would be decisive progress.

The Tet Offensive arrested progress on the pacification front. The American press described Tet as a terrible blow, particularly

against the pacification program. A

Washington Post

columnist claimed that the Tet attacks had “killed dead the pacification program.” The

Christian Science Monitor

agreed, saying that “pacification has been blown sky high.”

4

Indeed, the Tet attacks inflicted enormous damage. With the notable exception of the CAP villages around Da Nang, the shield

erected by American ground forces had failed to deflect main-force Communist units from moving through and attacking the rural

population. More than 40,000 civilians were killed or wounded with about 170,000 homes destroyed or damaged. Some 1 million

civilians fled the carnage to seek safety in squalid refugee camps. Tet significantly weakened the government’s standing in

the countryside as officials abandoned rural projects and joined the exodus. A CAP militiaman described his dismay: “That

attack scared everybody for years. From then, we could not be sure about the defenses of the army.”

5

However, Tet caused the Communists “agonizing and irreplaceable losses,” particularly among the best Viet Cong fighters and

most skilled members of the clandestine infrastructure who had emerged to assist and even participate in the attacks.

6

Because of these losses, the Tet Offensive created a vacuum of power in rural areas. It left the NLF hugely vulnerable to

a counterstroke, if the United States and its allies could deliver it.

Pacification’s High Water Mark

On the first day of July 1968, South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu announced a strategic response to the Tet Offensive.

After years of trial and error, American and South Vietnamese planners had finally adopted an integrated pacification program

that made population security the primary goal. On the same day, General Creighton Abrams replaced Westmoreland as MACV commander.

Under Abrams’s direction, a purportedly new strategy, the so-called one-war plan, emerged. It explicitly recognized the dual

need to keep the Communist main-force elements away from the populated areas and to root out the Viet Cong infrastructure.

The test case took place in the two northernmost provinces of I Corps; Quang Tri, adjacent to the demilitarized zone separating

North and South Vietnam, and Thua Thien, the location of the pi lot marine CAP villages near Phu Bai. This time, 30,000 American

and South Vietnamese regulars, including most of the 101st Airborne Division, provided an active buffer to confine enemy main-force

units to the remote hinterland. Reconnaissance units extended outward to the Laotian border to detect major enemy concentrations

and provide early warning to the regulars. Shielded by these operations, South Vietnamese militia and most especially National

Police secured the hamlets and villages along the coast.

Around the same time, South Viet namese political changes dramatically altered the calculus of the allied pacification push.

The Saigon government trumpeted a new land reform policy that when enacted in 1970 actually redistributed farmland to two

thirds of the tenant farmer families in South Vietnam. The United States introduced strains of so-called miracle rice that

greatly increased yields. The reopening of canals and roads allowed villagers to move their products to market. The net result

brought unprecedented prosperity. Simultaneously, the South Viet namese government expanded the local security forces, including

the Popular Forces and the People’s Self-Defense Force.

In January 1969 General Abrams told his commanders that pacification was the “gut issue.” He said that “if we are successful

in bashing down the VC and the government can raise its head up, the villages and hamlets can maintain their RF/PF [militia]

units and keep a few policemen around and people are not being assassinated all the time, then the government will mean something.”

7

Indeed, the period 1969 to 1972 witnessed steady progress in pacification.

What made the new approach, called the Area Security Concept, special was its focus on one objective: population security.

Also unique to this concept was the way it maintained its focus by dividing the two trial provinces in I Corps into geographic

regions (border, unpopulated hinterland, contested villages, secure villages), assigned appropriately tailored forces to each

region, and maintained coordination between the forces. By early 1969, every statistical indicator showed significant improvement

in rural security. By year’s end, the campaign was successfully separating the main-force units from the populated areas.

South Vietnamese militia and police, along with marine CAPs, had established a permanent presence in more than 90 percent

of the populated areas. For the first time, the enemy could not routinely slip between allied outposts. Captured documents

revealed that the enemy was having great difficulty maintaining morale. Both American and South Viet namese leaders had signed

on for the Area Security Concept. In 1970 they applied it to the entire I Corps. Unable to recruit sufficient replacements

from the local population, the Communists increasingly had to commit regulars from North Vietnam against the allied pacification

efforts. This was enormously costly, in part became urban North Vietnamese youth were no more at home in rural South Vietnam

than were urban South Vietnamese or Americans. Consequently, the Communists were reduced to assassination and terrorism to

maintain any hold over the people.