Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (5 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

Press reports full of bad popular science contributed to the spread of the simplistic notion that for every behaviour there was a gene, and that it could be discovered. This kind of talk was labelled ‘genetic determinism’:

27

the belief that we are destined to behave in certain ways because of our genetic make-up and neuronal wiring. However, very soon after the publication of the Human Genome, it became clear that, for complex behaviour, the effect of genes was relatively small. You are not violent because you carry a particular form of a gene. A direct causal relationship between genes and behaviour is valid only in some instances, when a single gene-defect leads to brain dysfunctions.

28

A classic example of this kind is Huntington’s disease, a neurodegenerative disorder that causes nerve cells to waste away, resulting in poor muscle coordination and dementia. If you happen to have, in chromosome 4 of your genome, an excessive repetition of a short DNA sequence, called a CAG repeat, no matter what you do, where you grew up or where you live, you will develop Huntington’s.

However, the origin of most behavioural traits is more complex than that. For one thing, most traits are ‘polygenic’, in that they involve the concerted interplay of many genes at the same time. MAOA is, so far, certainly the most studied and most credited gene with a link to aggression, but it is not the only one. What makes matters more complicated is that one gene can be responsible for more than one behaviour. So, while we refer to the ‘gene for’ Huntington’s disease, it is not correct to allude to the ‘gene for’ a complex trait, such as aggression. In fact, MAOA could be given even more labels. It could be called the ‘depression gene’ or the ‘gambling gene’, because variation at the level of its sequence has been found to be present in individuals manifesting those behaviours.

29

Taken alone, knowing which variation of a gene a person carries is useless in predicting whether he or she will manifest a particular behaviour. Many more variables are involved.

Genes and environment

One of these variables is unquestionably the environment. Behaviour can’t be studied without an appreciation of the circumstances in the external world where it manifests and which contributes to its emergence. Upbringing and traumatic experiences have strong effects on the development of personality. The environment interferes with the action of some of your genes and compromises the outcome of your development. For instance, identical twins who have exactly the same genome may end up with dissimilar personalities if reared in different families or communities.

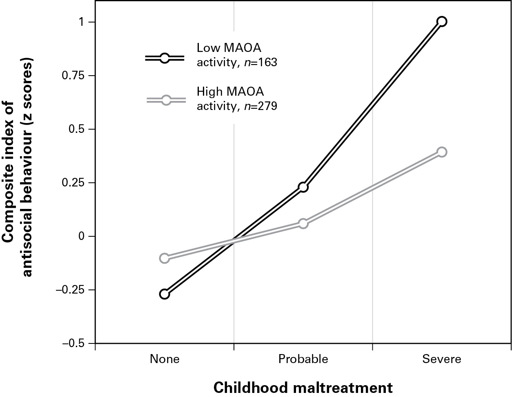

In the case of antisocial and violent behaviour, factors as diverse as childhood abuse or neglect, unstable family relationships or exposure to violence have all been found to be influential. A good proof of that came from a ground-breaking study conducted in New Zealand by a team led by Avshalom Caspi and Terrie Moffitt. Together with their colleagues, they set out to investigate whether variation in the MAOA gene could modulate the effect of these various kinds of childhood maltreatment. The researchers were lucky to have access to a cohort of people whose lives were progressively monitored from the age of three to twenty-six through surveys, family reports, tests and interviews. As best they could, they basically kept track of how the study participants grew up and led their lives. They found that, although MAOA alone had no large effect, it definitely modulated the impact of early-life maltreatment on the onset of antisocial behaviour, with people carrying the low-activity form of the gene being significantly more susceptible to the effects of abuse than those with the high-activity form (Fig. 3).

30

Over 80 per cent of those carrying the low-activity form ended up developing antisocial behaviour, but only if they had been exposed to maltreatment and abuse during their lives. By contrast, only 20 per cent of those carrying the malfunctioning form of the enzyme became violent if they had grown up in a healthy environment, without maltreatment.

Fig. 3 MAOA gene–environment interaction. After exposure to severe forms of maltreatment in childhood, individuals carrying the low-activity form of MAOA are more likely to manifest antisocial behaviour. (From Caspi

et al.

, 2002, reprinted with permission from American Association for the Advancement of Science)

Subsequent studies have independently come close to the same finding and tested other forms of environmental influences and measures of violent behaviour, including self-reports of aggression.

31

The overall message to bear in mind is that a gene alone does not translate into an emotion. A gene is not the

essence

of a behaviour. MAOA is not a synonym for either aggressive behaviour or criminality. The reason why genes are important and scientists keep hunting them down is that identifying a gene offers enticing clues about the general mechanism of a behaviour, particularly one that has clinical consequences. By finding a gene you can locate the neurochemical pathway that contributes to the manifestation of the symptoms and, of course, where in the brain the behaviour or disease is likely to be mapped.

However, no neuroscientist would ever tell you that variation in a gene such as MAOA is alone sufficient to determine violent behaviour or to make someone a criminal. Recently I came across the remarkable story of Jim Fallon, an American neuroscientist studying human behaviour, whose own family past had been stained with crime.

32

As part of a personal project, Fallon had examined brains of a few members of his family to evaluate their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Later, as talk of his studies spread at a family gathering, a previously undisclosed secret was revealed to him by his mother. In 1673 one of his ancestors was hanged for killing his own mother, becoming one of the first cases of matricide in the New World. Since then seven other episodes of murder had tarnished Jim’s family, the most infamous one perhaps being that of his distant cousin Lizzie Borden, who in 1892 in England was charged with and then acquitted of murdering with an axe both her father and her stepmother.

Dr Fallon, who works at the University of California, Irvine, is a carrier of the low-activity form of MAOA, and four other variants of genes which have been associated with violence. A scan of his brain also revealed reduced activity in orbitofrontal areas.

33

Fallon is basically in possession of at least two good ingredients that could potentially make him a violent killer. The chances that he would become one were greater than for other people lacking those biological attributes. Yet he did not. Apart from a tendency to indulge in risk-taking behaviour – like trout fishing in a corner of Kenya frequented by lions – nothing in his behaviour points to a threatening, violent attitude. Why? As Fallon himself explained, one essential ingredient was missing in the recipe for violence: a bad childhood. He says that as he grew up he did not experience trauma, nor was he exposed to any hostile environment. His was an easy childhood. Obviously, a deeper and more detailed investigation of his brain and life history, as well as those of his relatives, is warranted, but this interesting episode in the life of a neuroscientist studying behaviour shows the relative power of genes.

• • •

During the day I spent in the countryside I got to know Bruce a little better. He insisted that his DNA be tested. However, I was then able to persuade him to do more justice to science by enrolling in a study that involved a few hundred participants and measured the extent of their aggressive behaviour in relation not only to DNA variation, but also to information about childhood, upbringing and life history – all kept anonymous.

I tested my own DNA and, please permit the disclosure, I carry the high-activity form of the MAOA gene, so it seems consistent with the fact that I am not particularly prone to develop or manifest anger – to some extent, of course, because of the healthy environment where I grew up. But even if I were carrying the low-activity form it wouldn’t necessarily make me violent, any more than it did Fallon. It is the presence of the gene in combination with a hostile environment that increases the possibility of developing antisocial behaviour.

The brain on the stand

Ever since the discovery of a link between genes and aggression, lawyers have attempted to use such biological information as evidence that might justify their clients’ criminal actions on the basis that their

bad

genes or brains made them commit the crime.

Though never immune to imperfections, the system of justice follows a rather straightforward course. A suspect is charged with a violent crime. If they are found to have committed the crime, and voluntarily so – that is, with a guilty mind – they will be sentenced. An offender who is not in full possession of his or her mental capacities is accorded a lighter judgement. The task of ruling with certainty on a suspect’s mental capacity is a significant challenge for judges and medical experts alike, and the practice and outcome of such deliberation have depended on the available medical knowledge at any given time in history.

Until not long ago culpability in suspects with possible mental problems was ascertained solely on the basis of extensive psychiatric evaluations. Today the introduction of genetics and neuroscience into the courtroom shakes established notions of agency and culpability.

The first case in the world in which MAOA was used by the defence as a mitigating factor dates back to a 1994 US trial. Since then genetic evidence has been used worldwide in at least two hundred cases, of which about twenty were in the UK.

34

In 2009 a court in Italy cut the sentence to a convicted murderer by a year because he carried the low-activity version of the MAOA gene.

35

This became the first case in Europe in which genetic information affected a judicial sentence. The murderer was Abdelmalek Bayout, an Algerian citizen who stabbed and killed a man who insulted him about the kohl eye make-up he was wearing for religious reasons. In his verdict the judge who mitigated the sentence stated that he had found the MAOA evidence particularly compelling and embraced the motive put forward by the forensic experts, who claimed that Bayout’s genes would make him behave violently if provoked. In the US, even brain imaging has been introduced to alleviate the culpability of a defendant, but this has not been used in UK courts.

36

In early 2012 an interesting and informative survey of almost two hundred trial court judges in the US revealed that expert testimony providing biological evidence led judges to impose more lenient sentences when asked to deliberate on an offender in a fictional case of battery that was inspired by a real event.

37

On average, the judges cut the sentence by one year. However, the respondents to the survey disagreed on the weight that should be given to the biological information – which included MAOA genetic evidence as well as atypical amygdala function. For some, the biological evidence was a mitigating factor, because it represented an immutable, intrinsic cause for a behaviour over which the offender had no control. Interestingly, another group of judges argued the opposite and held the view that offenders with risky genes and risky brains would be a constant danger for society, declaring them prone to reoffend and unable to learn from punishment. This latter group of judges was more concerned with the future than with the past actions of the offenders. They didn’t feel comfortable with giving them back to society sooner than necessary.

The neuroscientist and author David Eagleman has been a hopeful proponent of the possibility of using neuroscience in the courtroom. He argues that the current legal notions of culpability and blameworthiness are bound to evolve in light of progress in neuroscience.

38

Whether it is a change in brain morphology, a clear genetic defect or a more subtle neurochemical alteration, there will always be a biological explanation for a criminal’s bad behaviour and such explanation will have to be taken into account during deliberation on a sentence. As a result, notions of volition, free will and blameworthiness will undergo transformation. For Eagleman, the question of blameworthiness is the wrong one to ask in the legal system, because in time neuroscience will reveal what elements in the brain biology of every offender can make him or her perpetrate a crime. A sentence given today to someone deemed culpable of committing a crime may change in a few years because of new ways to assess the biology of his or her brain. In line with the forward-looking judges in the survey, Eagleman concludes that the right question to ask is, how likely are the criminals to offend again, on the basis of their biology, which we will progressively understand better.