Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (33 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

Love is a desire that comes from the heart

Through an abundance of great pleasure

The eyes first generate love, and the heart gives it nourishment

. . . For the eyes represent to the heart the image

Of each thing they see, both good and bad . . .

4

Today, we know that the principal organ of love is not exactly the heart. The arrow of love, whatever this is, pierces the eye and from there it penetrates deep into the brain to the thalamus, where the visual message is processed and then passed on to the fusiform face area. When we meet another human being, the face is usually what we give most of our attention. A face gives away crucial clues to a person’s emotional state. The brain regions specializing in face recognition are all connected to the amygdala and to the prefrontal cortex, the two modulators of our emotional experience.

Indeed, many of the studies which have attempted to investigate romantic love have consisted in showing lovers in a brain scanner pictures of their beloved. You definitely cannot re-create the overall experience of a romantic encounter inside the scanner, but you can try to observe how a visual input arouses and sustains an emotional reaction in a person who is madly in love. In 2000, Andreas Bartels and Semir Zeki from University College London asked a group of young volunteers who declared themselves to be intensely in love to participate in a study that investigated the neural systems of romantic love.

5

During the scanning procedure, all participants viewed colour pictures of their loved partners who had requited their feelings for an average duration of a little over two years. In another similar study, Arthur Aron, Helen Fisher and colleagues from Rutgers University, New York, recruited an equal number of participants who also declared themselves to be madly in love, but they had been gripped by that sentiment for a maximum of seventeen months and, therefore, were in an earlier stage of a romantic relationship.

6

Alongside the brain activity measurements, all participants also ranked their romantic feelings by completing questionnaires that quantified their passion. They were asked to rate statements such as: ‘X always seems to be on my mind’, ‘I possess a powerful attraction for X’, ‘I yearn to know all about X’, or ‘I feel happy when I am doing something to make X happy’.

7

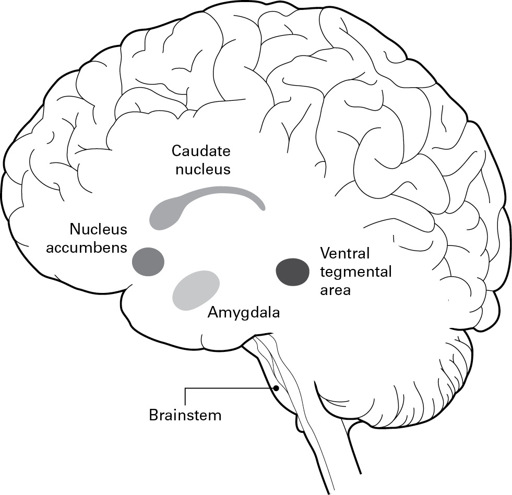

These may sound like common questions, but they do work for psychologists to assess the level of passion in lovers. The two studies dovetailed each other, revealing similar results. The areas of the brain that showed the highest activation were primarily two regions below the cortex. One is the ventral tegmental area, which covers the brainstem. The other is the caudate nucleus, a C-shaped structure at the centre of the brain, sitting astride the thalamus, and so named because it has a wider frontal part and a thinner tail – in Latin,

cauda

(Fig. 16). (The nucleus accumbens, another subcortical region, was also involved.) As I described in the previous chapter, all these regions primarily mediate reward and motivation and are bedewed with dopamine to awaken desire. Both the VTA and the caudate nucleus are also well connected to the visual system.

Fig. 16 Brain areas at work when gazing at the picture of a beloved in an fMRI scanner

Anyone who has ever had a crush will recognize the dopamine-related behaviour that pertains to it. The hyperactivity, the incredible motivation, the lack of fatigue – I definitely spent many sleepless nights writing poetry inspired by my infatuation.

When dopamine circulates in the brain, our minds are assisted in focusing our attention. Thus, when we are in love, dopamine makes us focus primarily on our beloved. Our thoughts are concentrated on one person. We can’t think of anything else. He or she ranks at the top of our priorities, and everyone else around becomes irrelevant or at any rate not as important. Such fixed and exclusive attention allows us also to concentrate on, and remember, details about our targets of desire. We remember what they wore, the exact words they said, we are able to describe the restaurant room where we had dinner with them, and their facial expression when we parted from them.

The fMRI images also revealed deactivation – a decrease or loss in activity – in the amygdala. The amygdala is central to our emotional life and the main repository of our fearful reactions. It is not surprising that during intense, but not so early, phases of romantic love, the sight of a beloved would result in less activity in this area, because the feeling of elation, trust and protection deriving from such a vision is likely to dissipate fear.

8

The low after the high

The unquestioned and unquestioning admiration for the object of our desires may not last indefinitely. Nor may the madness that characterized the nascent phases of passion. Over time, when we start to think clearly again, the beloved appears in a different light and may shed a misleading disguise. We shyly wonder: what was all that about?

After months of fervour and reciprocal admiration, the relationship with my boyfriend underwent a few considerable changes. It’s not that we grew tired of each other, but we came to discover features in us, and in the way we loved each other, that no longer inspired us. I won’t bother you with the details, but slowly I discovered a few unattractive edges in his attitude towards life. Sad as it can be, on a few occasions, it seemed that part of who he was had nothing to do with the person I thought I met on that April Sunday, and with whom I shared a few truly rewarding and affectionate moments. All in all, we realized we were not ready to embark on a search for the best way to live together. What changed, or what did we overlook when we first met?

We have heard this many times: love is basically blind. Not only is love blind, it has a lot of imagination. Inspired by an intense, but unrequited love experience with Mathilde Dembowski, whom he met in Milan in his thirties, the French author Stendhal (1783–1842) wrote a book on love, a large part of which is dedicated to the role of imagination. He compared falling for a person to a natural phenomenon which he named crystallization.

9

If you leave a stick for too long in a salt mine, when you take it out again, it will be fully covered with crystals and will assume a completely different aspect. It will no longer look like a stick. When we are attracted to someone a similar process occurs. We go ahead and imagine. We paint moments of happiness and harmony which nothing can guarantee will in reality take place or be sustained. Not only that. We decorate our object of desire with ornaments. Often, these embellishments are qualities we lack ourselves and that we would like to possess. This is not surprising. We are rarely attracted to something we already have. When I first met him, and during the early phases of our dating, the man whose face had struck me so powerfully looked simply flawless. When in love, our cognition is so disoriented we get euphoric at the merest glimpse of the qualities we long for. If we are eager to possess a great sense of humour, even an average joke made by our beloved sounds like a first-class stand-up set. An occasional beautiful scarf is a sign of timeless elegance and taste in clothes. An assertive remark about their beliefs and convictions is regarded as admirable solid self-confidence.

Interestingly, this recurrent aspect of love showed up in one of the brain-imaging studies that involved looking at pictures of the beloved. Significant neural deactivations were observed in some parts of the brain involved in the processing of negative emotions, the formulation of judgements towards others, as well as the perception of self in relation to others

10

– comparable to the neural changes observed during the suspension of disbelief in theatre watching.

In chapter 2, I explained at length how cautious we need to be when interpreting fMRI results and how difficult it is to allocate attributes of an emotion to distinct brain regions. In this particular case, trying to capture a sentiment as complex as romantic love in a brain scanner does sound like an incredibly ambitious, if not naive enterprise, diminishing the grandeur of the sentiment. However, on the face of it the silencing of these brain areas in states of romantic love would make sense for several reasons. Especially in the nascent phases of love, it is hard to make unbiased remarks about our objects of desire. We don’t seem to notice undesirable attributes in them. If we do, we don’t give them serious weight, or think that they could worsen; we can foresee growth only in their good qualities. If we express any judgement, that is mostly of a kind and complimentary nature. Basically, impartial judgement vanishes. The French philosopher Roland Barthes (1915–80) compares the lover to an artist whose world is ‘reversed’, ‘since in it each image is its own end’.

11

As if, sadly, in love there were nothing beyond the image. The beloved becomes a ghost, a mere artefact of the imagination.

Secondly, one of the most recurrent feelings in love is that we and those to whom we are attracted reach a strong and self-effacing unity of body and mind. This unity narrows physical and mental distance and, as our trust in the other grows, would also put aside any stark doubts about our sharing their beliefs and ideas. During love, we lower our barriers and defensive strategies. Of note in this regard is that some of the deactivations observed in measurements of romantic love show a close anatomical overlap with deactivations in a region of the frontal cortex observed during sexual arousal and orgasm. Sexual union is, after all, as near as humans can get towards the union of mind and body to which we aspire in romantic love.

12

Sight betrayed by emotion

So, early romantic passion can be a long, deceiving afterimage.

A bizarre neurological syndrome known as the Capgras delusion is a particularly intriguing example of how our sense of sight is betrayed by emotion. Patients with the Capgras delusion are otherwise lucid, but they regard a close acquaintance – usually someone with whom they are intimate – as an impostor. The syndrome was first reported in 1923 by Joseph Capgras, a French physician who wrote about the remarkable case of a 53-year-old woman, a certain Madame M.

13

Madame M had reported her husband’s sudden disappearance to the police. In truth, her husband was waiting for her at home. Madame M, however, had become convinced that the man she lived with was not her real husband but only a double who looked exactly like him and had stolen his identity. Over time, Madame M continued to experience similar delusions and fabricated a whole new reality for herself. Across a timespan of about five years, she reported having met thousands of unfamiliar messieurs – as she called them – who claimed to be her husband. Each was the double of the previous one and Madame M found something unfamiliar in each of them. Dr Capgras described Madame M’s imaginative condition as ‘chronic systematic delirium’ which he suspected had something to do with a misinterpretation of visual information.

14

Since Madame M, numerous similar cases have been reported. In a few, symptoms manifested as a consequence of brain injury. Studies have indicated that patients affected by the syndrome can recognize the faces of those they love, but are unable to experience any of the emotions that would normally arise from their familiarity. Simply recognizing somebody and experiencing an emotional connection with them are two different tasks within the brain. In broad outline, the former is mediated by an area called, appropriately, the fusiform face area. The latter is processed in the amygdala where our emotional memories are created and stored. Neurologists suspect that the Capgras symptoms might result from a specific disconnection, or miscommunication, between these two functionally different parts of the brain. Interestingly, the specificity of this missed link is confirmed by the fact that, in the physical absence of the presumed double, the patient can emotionally recognize their real partner – if they hear their voice on the phone, for instance.

The Capgras syndrome has fascinated many.

15

When I first heard about it I became interested in using it as a prism with which to examine love.

16

For how many of us have never had the experience that we stop recognizing those we are attracted to, if not in a literal sense, then emotionally? After all, the image we cherish of those whom we think we know so intimately can sometimes turn out to be distant from reality. As we discover new and unexpected faults that we never noticed before, those whom we love can gradually begin to feel like strangers to us. In effect, they become impostors.