Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) (20 page)

Read Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Online

Authors: Jules Verne

BOOK: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

8.83Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“Ah! You’re coming around to my way of thinking, my boy,” said the professor laughing.

A jet of water spurted out of the rock and hit the opposite wall.

“I’m not coming around to it, I’m with it.”

“Just a moment! Let’s start by resting for a few hours.”

I had really forgotten that it was night. The chronometer soon informed me of that fact; and soon all of us, sufficiently restored and refreshed, fell into a deep sleep.

XXIV

THE NEXT MORNING, WE had already forgotten all our sufferings. At first, I was amazed that I was no longer thirsty, and wondered about the reason. The creek murmuring at my feet provided the answer.

We had breakfast, and drank of this excellent ferrous water. I felt completely restored, and quite resolved to push on. Why would not so firmly convinced a man as my uncle succeed, with so industrious a guide as Hans and so ‘determined’ a nephew as myself? Such were the beautiful ideas that floated into my brain! If it had been proposed to me to return to the summit of Snaefells, I would have indignantly declined.

But fortunately, all we had to do was descend. “Let’s take off!” I exclaimed, awakening the ancient echoes of the globe with my enthusiastic tone.

We resumed our walk on Thursday at eight in the morning. The granite tunnel meandered in sinuous contortions and confronted us with unexpected turns in what appeared to be the intricacies of a labyrinth; but, on the whole, its main direction was always southeast. My uncle constantly checked his compass to keep track of the ground we had covered.

The tunnel stretched almost horizontally, with at most two inches of slope per fathom. The stream ran gently murmuring at our feet. I compared it to a friendly spirit guiding us underground, and with my hand I caressed the tepid naiad whose songs accompanied our steps. My good mood spontaneously led me to this mythological train of thought.

As for my uncle, a man of the vertical, he raged against the horizontal route. His path prolonged itself indefinitely, and instead of sliding down along the earth’s radius, in his words, it followed the hypotenuse. But we did not have any choice, and as long as we were making progress toward the center, however slowly, we could not complain.

From time to time, at any rate, the slopes became steeper; the naiad began to rush down with a roar, and we descended with her to a greater depth.

On the whole, that day and the next we made considerable headway horizontally, very little vertically.

On Friday evening, July 10, according to our calculations, we were thirty leagues south-east of Reykjavik, and at a depth of two and a half leagues.

At our feet a rather frightening well then opened up. My uncle could not keep from clapping his hands when he calculated the steepness of its slopes.

“This’ll take us a long way,” he exclaimed, “and easily, because the projections in the rock make for a real staircase!”

The ropes were tied by Hans in such a way as to prevent any accident. The descent began. I can hardly call it dangerous, because I was already familiar with this kind of exercise.

This well was a narrow cleft cut into the rock, of the kind that’s called a ‘fault.’ The contraction of the earth’s frame in its cooling period had obviously produced it. If it had at one time been a passage for eruptive matter thrown up by Snaefells, I could not understand why this material had left no trace. We kept going down a kind of spiral staircase which seemed almost to have been made by the hand of man.

Every quarter of an hour we were forced to stop, to get the necessary rest and restore the flexibility of our knees. We then sat down on some projecting rock, let our legs hang down, and chatted while we ate and drank from the stream.

Needless to say, in this fault the Hansbach had turned into a waterfall and lost some of its volume; but there was enough, more than enough, to quench our thirst. Besides, on less steep inclines, it would of course resume its peaceable course. At this moment it reminded me of my worthy uncle, in his frequent fits of impatience and anger, whereas on gentle slopes it ran with the calmness of the Icelandic hunter.

On July 11 and 12, we kept following the spiral curves of this singular well, penetrating two more leagues into the earth’s crust, which added up to a depth of five leagues below sea level. But on the 13th, about noon, the fault fell in a much gentler slope of about forty-five degrees towards the south-east.

The path then became easy and perfectly monotonous. It could hardly be otherwise. The journey could not vary by changes in the landscape.

Finally on Wednesday, the 15th, we were seven leagues underground and about fifty leagues away from Snaefells. Although we were a little tired, our health was still reassuringly good, and the medicine kit had not yet been opened.

My uncle noted every hour the indications of the compass, the chronometer, the manometer, and the thermometer just as he has published them in his scientific report of his journey. He could therefore easily identify our location. When he told me that we had gone fifty leagues horizontally, I could not repress an exclamation.

“What’s the matter?” he exclaimed.

“Nothing, I was just thinking.”

“Thinking what?”

“That if your calculations are correct we’re no longer underneath Iceland.”

“Do you think so?”

“It’s easy enough to find out.”

I made my compass measurements on the map.

“I’m not mistaken,” I said. “We have left Cape Portland behind, and those fifty leagues place us right under the sea.”

“Right under the sea,” my uncle repeated, rubbing his hands.

“So the ocean is right above our heads!” I exclaimed.

“Bah! Axel, what would be more natural? Aren’t there coal mines at Newcastle that extend far under the sea?”

It was all very well for the professor to call this so simple, but the idea that I was walking around under masses of water kept worrying me. And yet it really mattered very little whether it was the plains and mountains of Iceland that were suspended over our heads or the waves of the Atlantic, as long as the granite structure was solid. At any rate, I quickly got used to this idea, for the tunnel, sometimes straight, sometimes winding, as unpredictable in its slopes as in its turns, but always going south-east and penetrating ever deeper, led us rapidly to great depths.

Four days later, on Saturday, July 18, in the evening, we arrived at a kind of rather large grotto; my uncle paid Hans his three weekly rix-dollars, and it was settled that the next day, Sunday, should be a day of rest.

XXV

I THEREFORE WOKE UP on Sunday morning without the usual preoccupations of an immediate departure. And even though we were in the deepest abyss, that was still pleasant. In any case, we had gotten used to this troglodyte life. I hardly thought of sun, stars, moon, trees, houses, and towns anymore, or of any of those earthly superfluities which sublunary beings have turned into necessities. Being fossils, we did not care about such useless wonders.

The grotto was an immense hall. Along its granite floor our faithful stream ran gently. At this distance from its spring, the water had the same temperature as its surroundings and could be drunk without difficulty.

After breakfast the professor wanted to devote a few hours to putting his daily notes in order.

“First,” he said, “I’ll calculate our exact position. I hope, after our return, to draw a map of our journey, a kind of vertical section of the globe which will retrace the itinerary of our expedition.”

“That’ll be very interesting, Uncle; but are your observations sufficiently accurate?”

“Yes; I’ve carefully noted the angles and the slopes. I’m sure there’s no mistake. Let’s see where we are now. Take your compass, and note the direction.”

I looked at the instrument and replied after careful study:

“East-a-quarter-south-east.”

“Good,” answered the professor, writing down the observation and calculating quickly. “I infer that we’ve gone eighty-five leagues from our point of departure.”

“So we’re under the mid-Atlantic?”

“Exactly.”

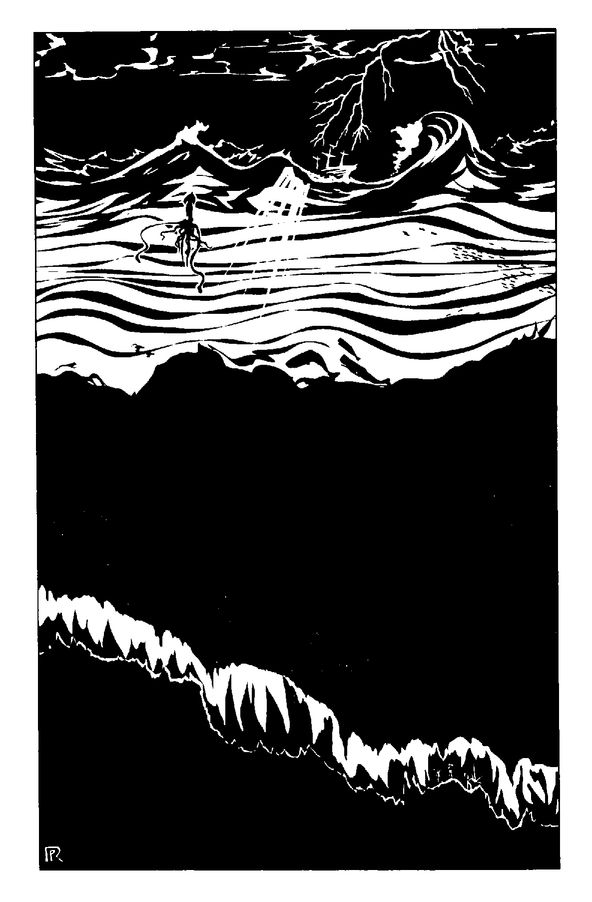

“And perhaps at this very moment there’s a storm unleashed above, and ships over our heads are being tossed by the waves and the hurricane?”

“Possible.”

“And whales are lashing the roof of our prison with their tails?”

“Don’t worry, Axel, they won’t manage to break it. But let’s go back to our calculation. We’re eighty-five leagues south-east of the foot of Snaefells, and I estimate that we’re at a depth of sixteen leagues.”

“Sixteen leagues!” I exclaimed.

“No doubt.”

“But that’s the upper limit that science has calculated for the thickness of the earth’s crust.”

“I don’t deny it.”

“And here, according to the law of increasing temperature, there should be a heat of 1,500°C!”

“‘Should,’ my boy.”

“And all this solid granite could not remain solid and would be completely molten.”

“You see that it’s not so, and that, as so often happens, facts contradict theories.”

“I’m forced to agree, but it does amaze me.”

“What does the thermometer say?”

“27 and 6/10°C.”

“Therefore the scholars are wrong by 1,474 and 4/10°. So the proportional increase in temperature is a mistake. So Humphry Davy was right. So I am not wrong in following him. What do you say now?”

“Nothing.”

In truth, I had a great deal to say. In no way did I accept Davy’s theory. I still believed in core heat, although I did not feel its effects. I preferred to believe, really, that this chimney of an extinct volcano was covered with a refractive lava coating that did not allow the heat to pass through its walls.

But without bothering to find new arguments, I simply accepted the situation such as it was.

“Uncle,” I resumed, “I believe all your calculations are accurate, but allow me to draw one rigorous conclusion from them.”

“Go ahead, my boy.”

“At the latitude of Iceland, where we now are, the radius of the earth is about 1,583 leagues?”

“1,583 leagues and 1/3.”

“Let’s say 1,600 leagues in round numbers. Out of 1,600 leagues we have covered twelve?”

“Just as you say.”

“Perhaps at this very moment there’s a storm unleashed above.”

“And these twelve by going 85 leagues diagonally?”

“Exactly.”

“In about twenty days?”

“In twenty days.”

“Now, sixteen leagues are the hundredth part of the earth’s radius. At this rate we’ll take two thousand days, or nearly five years and a half, to get to the center.”

The professor gave no answer.

“Without mentioning that if a vertical depth of sixteen leagues can be reached only by a diagonal descent of eighty-four, we have to go eight thousand miles to the south-east, and we’ll emerge from some point in the earth’s circumference long before we get to the center!”

“To Hell with your calculations!” replied my uncle in a fit of rage. “To Hell with your hypotheses! What’s the basis of them all? How do you know that this passage doesn’t run straight to our goal? Besides, we have a precedent. What I’m doing, another man has done before me, and where he’s succeeded, I’ll succeed in my turn.”

“I hope so; but, still, I may be permitted—”

“You’re permitted to hold your tongue, Axel, if you’re going to talk in that irrational way.”

I could see the awful professor threatening to reappear under the surface of the uncle, and I took the hint.

“Now look at your manometer. What does it indicate?”

“Considerable pressure.”

“Good; so you see that by going down gradually, and by getting accustomed to the density of the atmosphere, we don’t suffer at all.”

“Not at all, except a little pain in the ears.”

Other books

Birthright: Battle for the Confederation- Turmoil by Ryan Krauter

Who Invited the Ghost to Dinner: A Ghost Writer Mystery by Teresa Watson

The Summer Guest by Alison Anderson

The Day the Rebels Came to Town by Robert Hough

El vizconde demediado by Italo Calvino

Sector General Omnibus 3 - General Practice by James White

Facts of Life by Gary Soto

Noah: Scifi Alien Invasion Romance (Hell Squad Book 6) by Anna Hackett

Fool's Gold by Byrnes, Jenna

Death and the Arrow by Chris Priestley