Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) (16 page)

Read Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Online

Authors: Jules Verne

BOOK: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

5.63Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

My uncle could no longer control himself. It was indeed enough to irritate a more patient man than him, because this was really shipwreck before leaving the port.

But Heaven always mixes great grief with great joy, and for Professor Lidenbrock there was satisfaction equal to his desperate troubles in store.

It softly brushed the edge of the middle chimney.

The next day the sky was again overcast; but on the 29th of June, the next-to-last day of the month, a change of weather came with the change of the moon. The sun poured a flood of light down the crater. Every hill, every stone, every roughness got its share of the luminous flow and instantly threw its shadow on the ground. Among them all, that of Scartaris was outlined with a sharp edge and began to move slowly in the opposite direction from that of the radiant star.

My uncle turned with it.

At noon, when it was shortest, it softly brushed the edge of the middle chimney.

“There it is! there it is!” shouted the professor. “To the center of the globe!” he added in Danish.

I looked at Hans.

“Forüt!” he said quietly.

“Forward!” replied my uncle.

It was thirteen minutes past one.

XVII

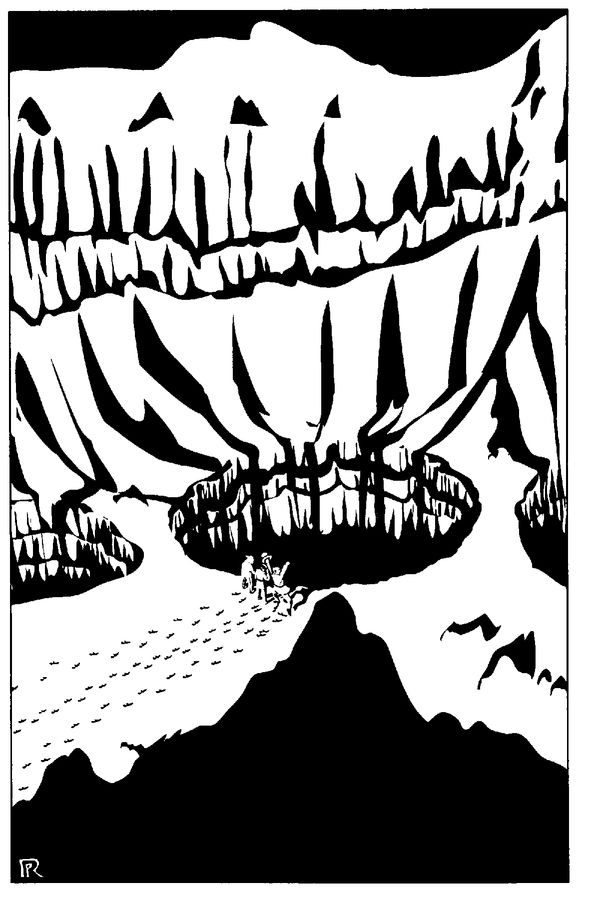

THE REAL JOURNEY BEGAN. So far our effort had overcome all difficulties, now difficulties would really spring up at every step.

I had not yet ventured to look down at the bottomless pit into which I was about to plunge. The moment had come. I could still either take my part in the venture or refuse to undertake it. But I was ashamed to withdraw in front of the hunter. Hans accepted the adventure so calmly, with such indifference and such perfect disregard for any danger that I blushed at the idea of being less brave than he. If I had been alone I might have once more tried a series of long arguments; but in the presence of the guide I held my peace; my memory flew back to my pretty Virland girl, and I approached the central chimney.

I have already mentioned that it was a hundred feet in diameter, and three hundred feet in circumference. I bent over a projecting rock and gazed down. My hair stood on end with terror. The feeling of emptiness overcame me. I felt the center of gravity shifting in me, and vertigo rising up to my brain like drunkenness. There is nothing more treacherous than this attraction toward the abyss. I was about to fall. A hand held me back. Hans’. I suppose I had not taken as many lessons in abysses as I should have at the Frelsers Kirke in Copenhagen.

But however briefly I had looked down this well, I had become aware of its structure. Its almost perpendicular walls were bristling with innumerable projections which would facilitate the descent. But if there was no lack of steps, there was still no rail. A rope fastened to the edge of the aperture would have been enough to support us. But how would we unfasten it when we arrived at the lower end?

My uncle used a very simple method to overcome this difficulty. He uncoiled a cord as thick as a finger and four hundred feet long; first he dropped half of it down, then he passed it round a lava block that projected conveniently, and threw the other half down the chimney. Each of us could then descend by holding both halves of the rope with his hand, which would not be able to unroll itself from its hold; when we were two hundred feet down, it would be easy to retrieve the entire rope by letting one end go and pulling down by the other. Then we would start this exercise over again ad

infinitum

.

infinitum

.

“Now,” said my uncle, after having completed these preparations, “let’s see about our loads. I’ll divide them into three lots; each of us will strap one on his back. I mean only fragile articles.”

The audacious professor obviously did not include us in this last category.

“Hans,” he said, “will take charge of the tools and a part of the food supplies; you, Axel, will take another third of the food supplies, and the weapons; and I will take the rest of the food supplies and the delicate instruments.”

“But,” I said, “the clothes, and that mass of ladders and ropes, who’ll take them down?”

“They’ll go down by themselves.”

“How so?” I asked.

“You’ll see.”

My uncle liked to use extreme means, without hesitation. At his order, Hans put all the unbreakable items into one package, and this packet, firmly tied up, was simply thrown down into the chasm.

I heard the loud roar of the displaced layers of air. My uncle, leaning over the abyss, followed the descent of the luggage with a satisfied look, and only rose up again when he had lost sight of it.

“Well,” he said. “Now it’s our turn.”

I ask any sensible man if it was possible to hear those words without a shudder!

The professor tied the package of instruments to his back; Hans took the tools, myself the weapons. The descent started in the following order: Hans, my uncle, and myself. It was carried out in profound silence, broken only by the fall of loose stones into the abyss.

I let myself fall, so to speak, frantically clutching the double cord with one hand and buttressing myself from the wall with the other with my stick. One single idea obsessed me: I feared that the rock from which I was hanging might give way. This cord seemed very fragile for supporting the weight of three people. I used it as little as possible, performing miracles of equilibrium on the lava projections which my foot tried to seize like a hand.

When one of these slippery steps shook under Hans’ steps, he said in his quiet voice:

“Gif akt!”

“Attention!” repeated my uncle.

In half an hour we were standing on the surface of a rock wedged in across the chimney from one side to the other.

Hans pulled the rope by one of its ends, the other rose in the air; after passing the higher rock it came down again, bringing with it a rather dangerous shower of bits of stone and lava.

Leaning over the edge of our narrow platform, I noticed that the bottom of the hole was still invisible.

The same maneuver was repeated with the cord, and half an hour later we had descended another two hundred feet.

I do not suppose even the most obsessed geologist would have studied the nature of the rocks that we were passing under such circumstances. As for me, I hardly troubled myself about them. Pliocene, Miocene, Eocene, Cretaceous, Jurassic, Triassic, Permian, Carboniferous, Devonian, Silurian, or Primitive was all one to me. But the professor, no doubt, was pursuing his observations or taking notes, for during one of our stops he said to me:

“The farther I go the more confident I am. The order of these volcanic formations absolutely confirms Davy’s theories. We’re now in the midst of primordial soil in which the chemical reaction of metals catching flame through the contact of water and air occurred. I absolutely reject the theory of heat at the center of the earth. We’ll see, in any case.”

Always the same conclusion. Of course, I was not inclined to argue. My silence was taken for consent, and the descent continued.

After three hours, and I still did not see bottom of the chimney. When I raised my head I noticed how the opening was getting smaller. Its walls, due to their gentle slope, were drawing closer to each other, and it was beginning to grow darker.

Still we kept descending. It seemed to me that the stones breaking loose from the walls fell with a duller echo, and that they must be reaching the bottom of the chasm promptly.

As I had taken care to keep an exact account of our maneuvers with the rope, I could tell exactly what depth we had reached and how much time had passed.

We had by that time repeated this maneuver fourteen times, each one taking half an hour. So it had been seven hours, plus fourteen quarter of an hour or a total of three hours to rest. Altogether, ten hours and a half. We had started at one, it must now be eleven o’clock.

As for the depth we had reached, these fourteen rope maneuvers of 200 feet each added up to 2,800 feet.

At that moment I heard Hans’ voice.

“Stop!” he said.

I stopped short just as I was going to hit my uncle’s head with my feet.

“We’ve arrived,” said the latter.

“Where?” I said, sliding down next to him.

“At the bottom of the vertical chimney,” he answered.

“Is there any way out?”

“Yes, a kind of tunnel that I can see and which veers off to the right. We’ll see about that tomorrow. Let’s have dinner first, and afterwards we’ll sleep.”

The darkness was not yet complete. We opened the bag with the supplies, ate, and each of us lay down as well as he could on a bed of stones and lava fragments.

When I lay on my back, I opened my eyes and saw a sparkling point of light at the extremity of this 3,000-foot long tube, which had now become a vast telescope.

It was a star without any glitter, which by my calculation should be ß of

Ursa minor.

Ursa minor.

Then I fell into a deep sleep.

XVIII

AT EIGHT IN THE morning a ray of daylight came to wake us up. The thousand facets of lava on the walls received it on its passage, and scattered it like a shower of sparks.

There was light enough to distinguish surrounding objects.

“Well, Axel, what do you say?” exclaimed my uncle, rubbing his hands. “Did you ever spend a quieter night in our little house in the Königstrasse? No noise of carts, no cries of merchants, no boatmen vociferating!”

“No doubt it’s very quiet at the bottom of this well, but there’s something alarming in the quietness itself.”

“Now come!” my uncle exclaimed; “if you’re frightened already, what will you be later on? We’ve not gone a single inch yet into the bowels of the earth.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that we’ve only reached the ground level of the island. This long vertical tube, which terminates at the mouth of the crater, has its lower end at about sea level.”

“Are you sure of that?”

“Quite sure. Check the barometer.”

In fact, the mercury, which had gradually risen in the instrument as we descended, had stopped at twenty-nine inches.

“You see,” said the professor, “we only have a pressure of one atmosphere, and can’t wait for the manometer to take the place of the barometer.”

And indeed, this instrument would become useless as soon as the weight of the atmosphere exceeded the pressure at sea level.

“But,” I said, “isn’t there reason to fear that this steadily increasing pressure will become very painful?”

“No; we’ll descend at a slow pace, and our lungs will become used to breathing a denser atmosphere. Aeronauts lack air as they rise to high elevations, and we’ll perhaps have too much. But I prefer that. Let’s not waste a moment. Where’s the packet we sent down before us?”

I then remembered that we had searched for it in vain the evening before. My uncle questioned Hans who, after having looked around attentively with his hunter’s eyes, replied:

“Der huppe!”

“Up there.”

And so it was. The bundle had been caught by a projection a hundred feet above us. Immediately the agile Icelander climbed up like a cat, and in a few minutes the package was in our possession.

“Now,” said my uncle, “let’s have breakfast, but let’s have it like people who may have a long route in front of them.”

The biscuit and extract of meat were washed down with a draught of water mingled with a little gin.

Breakfast over, my uncle drew from his pocket a small notebook, intended for scientific observations. He consulted his instruments, and recorded:

Monday, July 1

Chronometer: 8.17 a.m.

Barometer: 29 7/12”.

Thermometer: 6°C.

Direction: E.S.E.

Barometer: 29 7/12”.

Thermometer: 6°C.

Direction: E.S.E.

This last observation applied to the dark tunnel, and was indicated by the compass.

“Now, Axel,” exclaimed the professor with enthusiasm, “we’re really going into the bowels of the globe. At this precise moment the journey begins.”

That said, my uncle took the Ruhmkorff device that was hanging from his neck with one hand; and with the other he connected the electric current with the coil in the lantern, and a rather bright light dispersed the darkness of the passage.

Hans carried the other device, which was also turned on. This ingenious electrical appliance would enable us to go on for a long time by creating an artificial light even in the midst of the most inflammable gases.

“Let’s go!” exclaimed my uncle.

Each of us took his package. Hans pushed the load of cords and clothes before; and, myself going last, we entered the tunnel.

At the moment of penetrating into this dark tunnel, I raised my head, and saw for the last time through the length of that vast tube the sky of Iceland, “which I was never to behold again.”

The lava, in the last eruption of 1229, had forced a passage through this tunnel. It still lined the walls with a thick and glistening coat. The electric light was here intensified a hundredfold by reflection.

Other books

Armchair Nation by Joe Moran

The Dragon's Appraiser: Part One by Viola Rivard

Sue-Ellen Welfonder - MacKenzie 07 by Highlanders Temptation A

Whatever You Like by Maureen Smith

Medstar I: Médicos de guerra by Steve Perry Michael Reaves

A Club Esoteria Wedding [Club Esoteria 11] (Siren Publishing Classic) by Cooper McKenzie

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion by Paul A. LaViolette, Ph.D.

An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917-1963 by Robert Dallek

The Watcher's Eyes (The Binders Game Book 2) by Holmberg, D.K.