Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (67 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

Mr Norrell was quite happy to employ Pevensey's magic, since he had settled it in his own mind long ago that Pevensey was a man. As to the letters — since they contained no word of magic he did not concern himself with them. Jonathan Strange took a different view. According to him only one question needed to be asked and answered in order to settle the matter: would Martin Pale have taught a woman magic? The answer was, again according to Strange, yes. After all Martin Pale claimed to have been taught by a woman — Catherine of Winchester.

3 Thaddeus Hickman (1700–38), author of a life of Martin Pale.

4 The ivy promised to bind England's enemies Briars and thorns promised to whip them The hawthorn said he would answer any question The birch said he would make doors to other countries The yew brought us weapons The raven punished our enemies The oak watched the distant hills The rain washed away all sorrow This traditional English saying supposedly lists the various contracts which John Uskglass, the Raven King, made on England's behalf with the forests.

36

All the mirrors of the world

November 1814

T

HE VILLAGE OF Hampstead is situated five miles north of London. In our grandfathers' day it was an entirely unremarkable collection of farmhouses and cottages, but the existence of so rustic a spot close to London attracted large numbers of people to go there to enjoy the sweet air and verdure. A racecourse and bowling-green were built for their amusement. Bun shops and tea-gardens provided refreshment. Rich people bought summer cottages there and Hampstead soon became what it is today: one of the favourite resorts of fashionable London society. In a very short space of time it has grown from a country village to a place of quite respectable size - almost a little town.

Two hours after Sir Walter, Colonel Grant, Colonel Manning- ham and Jonathan Strange had quarrelled with the Nottingham- shire gentleman a carriage entered Hampstead on the London road and turned into a dark lane which was overhung with elder bushes, lilacs and hawthorns. The carriage drove to a house at the end of the lane where it stopped and Mr Drawlight got out.

The house had once been a farmhouse, but it had been much improved in recent years. Its small country windows - more useful for keeping out the cold than letting in the light - had all been made large and regular; a pillared portico had replaced the mean country doorway; the farm-yard had been entirely swept away and a flower garden and shrubbery established in its place.

Mr Drawlight knocked upon the door. A maidservant answered his knock and immediately conducted him to a drawing-room. The room must once have been the farmhouse-parlour, but all signs of its original character had disappeared beneath costly French wallpapers, Persian carpets and English furniture of the newest make and style.

Drawlight had not waited there more than a few minutes when a lady entered the room. She was tall, well-formed and beautiful. Her gown was of scarlet velvet and her white neck was set off by an intricate necklace of jet beads.

Through an open door across the passageway could be glimpsed a dining-parlour, as expensively got up as the drawing-room. The remains of a meal upon the table shewed that the lady had dined alone. It seemed that she had put on the red gown and black necklace for her own amusement.

“Ah, madam!" cried Drawlight leaping up. “I hope you are well?"

She made a little gesture of dismissal. “I suppose I am well. As well as I can be with scarcely any society and no variety of occupation."

“What!" cried Drawlight in a shocked voice. “Are you all alone here?"

“I have one companion - an old aunt. She urges religion upon me."

“Oh, madam!" cried Drawlight. “Do not waste your energies upon prayers and sermons. You will get no comfort there. Instead, fix your thoughts upon

revenge

."

“I shall. I do," she said simply. She sat down upon the sopha opposite the window. “And how are Mr Strange and Mr Norrell?"

“Oh, busy, madam! Busy, busy, busy! I could wish for their sakes, as well as yours, that they were less occupied. Only yesterday Mr Strange inquired most particularly after you. He wished to know if you were in good spirits. `Oh! Tolerable,' I told him, `merely tolerable.' Mr Strange is shocked, madam, frankly shocked at the heartless behaviour of your relations."

“Indeed? I wish that his indignation might shew itself in more practical ways," she said coolly. “I have paid him more than a hundred guineas and he has done nothing. I am tired of trying to arrange matters through an intermediary, Mr Drawlight. Convey to Mr Strange my compliments. Tell him I am ready to meet him wherever he chuses at any hour of the day or night. All times are alike to me. I have no engagements."

“Ah, madam! How I wish I could do as you ask. How Mr Strange wishes it! But I fear it is quite impossible."

“So you say, but I have heard no reason - at least none that satisfies me. I suppose Mr Strange is nervous of what people will say if we are seen together. But our meeting may be quite private. No one need know."

“Oh, madam! You have quite misunderstood Mr Strange's character! Nothing in the world would please him so much as an opportunity to shew the world how he despises your persecutors. It is entirely upon your account that he is so circumspect. He fears . . ."

But what Mr Strange feared the lady never learnt, for at that moment Drawlight stopt suddenly and looked about him with an expression of the utmost perplexity upon his face. “What in the world was that?" he asked.

It was as if a door had opened somewhere. Or possibly a series of doors. There was a sensation as of a breeze blowing into the house and bringing with it the half-remembered scents of childhood. There was a shift in the light which seemed to cause all the shadows in the room to fall differently. There was nothing more definite than that, and yet, as often happens when some magic is occurring, both Drawlight and the lady had the strongest impression that nothing in the visible world could be relied upon any more. It was as if one might put out one's hand to touch any thing in the room and discover it was no longer there.

A tall mirror hung upon the wall above the sopha where the lady sat. It shewed a second great white moon in a second tall dark window and a second dim mirror-room. But Drawlight and the lady did not appear in the mirror-room at all. Instead there was a kind of an indistinctness, which became a sort of shadow, which became the dark shape of someone coming towards them. From the path which this person took, it could clearly be seen that the mirror-room was not like the original at all and that it was only by odd tricks of lighting and perspective - such as one might meet with in the theatre - that they appeared to be the same. It seemed that the mirror-room was actually a long corridor. The hair and coat of the mysterious figure were stirred by a wind which could not be felt in their own room and, though he walked briskly towards the glass which separated the two rooms, it was taking him some time to reach it. But finally he reached the glass and then there was a moment when his dark shape loomed very large behind it and his face was still in shadow.

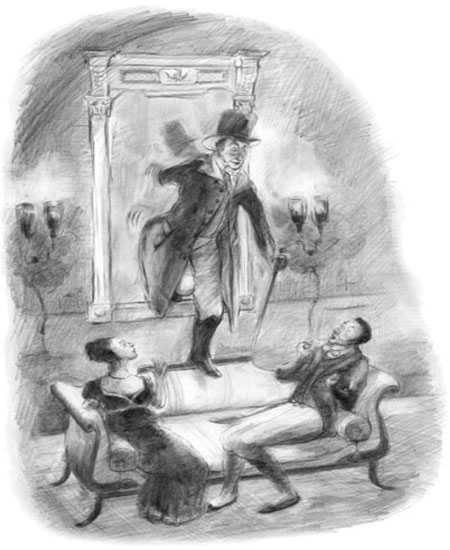

Then Strange hopped down from the mirror very neatly, smiled his most charming smile and bid both Drawlight and the lady, “Good evening."

He waited a moment, as if allowing someone else time to speak and then, when no one did, he said, “I hope you will be so kind, madam, as to forgive the lateness of my visit. To say the truth the way was a little more meandering than I had anticipated. I took a wrong turning and very nearly arrived in . . . well, I do not quite know where."

He paused again, as if waiting for someone to invite him to sit down. When no one did, he sat down anyway.

Drawlight and the lady in the red gown stared at him. He smiled back at them.

“I have been getting acquainted with Mr Tantony," he told Drawlight. “A most pleasant gentleman, though not very talka- tive. His friend, Mr Gatcombe, however, told me all I wished to know."

“You are Mr Strange?" asked the lady in the red gown.

“I am, madam."

“This is most fortunate. Mr Drawlight was just explaining to me why you and I could never meet."

“It is true, madam, that until tonight circumstances did not favour our meeting. Mr Drawlight, pray make the introductions."

Drawlight muttered that the lady in the red gown was Mrs Bullworth.

Strange rose, bowed to Mrs Bullworth and sat down again.

“Mr Drawlight has, I believe, told you of my horrible situation?" said Mrs Bullworth.

Strange made a small gesture with his head which might have meant one thing or might have meant another thing or might have meant nothing at all. He said, “A narration by an unconnected person can never match the tale told by someone intimately concerned with the events. There may be vital points which Mr Drawlight has, for one reason or another, omitted. Indulge me, madam. Let me it hear from you."

“All?"

“All."

“Very well. I am, as you know, the daughter of a gentleman in Northamptonshire. My father's property is extensive. His house and income are large. We are among the first people in that county. But my family have always encouraged me to believe that with my beauty and accomplishments I might occupy an even higher position in the world. Two years ago I made a very advantageous marriage. Mr Bullworth is rich and we moved in the most fashionable circles. But still I was not happy. In the summer of last year I had the misfortune to meet a man who is everything Mr Bullworth is not: handsome, clever, amusing. A few short weeks were enough to convince me that I preferred this man to any one I had ever seen." She gave a little shrug of her shoulders. “Two days before Christmas I left my husband's house in his company. I hoped - indeed expected - to divorce Mr Bullworth and marry him. But that was not his intention. By the end of January we had quarrelled and my friend had deserted me. He returned to his house and all his usual pursuits, but there was to be no such revival of a former life for me. My husband cast me off. My friends refused to receive me. I was forced back upon the mercy of my father. He told me that he would provide for me for the rest of my life, but in return I must live in perfect retirement. No more balls for me, no more parties, no more friends. No more any thing." She gazed into the distance for a moment, as if in contemplation of all that she had lost, but just as quickly she shook off her melancholy and declared, “And now to business!" She went to a little writing-table, opened a drawer and drew out a paper which she offered to Strange. “I have, as you suggested, made a list of all the people who have betrayed me," she said.

“Ah, I told you to make a list, did I?" said Strange, taking the paper. “How businesslike I am! It is quite a long list."

“Oh!" said Mrs Bullworth. “Every name will be considered a separate commission and you shall have your fee for each. I have taken the liberty of writing by each name the punishment which I believe ought to be theirs. But your superior knowledge of magic may suggest other, more appropriate fates for my enemies. I should be glad of your recommendations."

“ `Sir James Southwell. Gout,' " read Strange.

“My father," explained Mrs Bullworth. “He wearied me to death with speeches upon my wicked character and exiled me for ever from my home. In many ways it is he who is the author of all my miseries. I wish I could harden my heart enough to decree some more serious illness for him. But I cannot. I suppose that is what is meant by the weakness of women."

“Gout is exceedingly painful," observed Strange. “Or so I am told."

Mrs Bullworth made a gesture of impatience.

“ `Miss Elizabeth Church,' " continued Strange. “ `To have her engagement broken off.' Who is Miss Elizabeth Church?"

“A cousin of mine - a tedious, embroidering sort of girl. No one ever paid her the least attention until I married Mr Bullworth. Yet now I hear she is to be married to a clergyman and my father has given her a banker's draft to pay for wedding clothes and new furniture. My father has promised Lizzie and the clergyman that he will use his interest to get them all sorts of preferments. Their way is to be made easy. They are to live in York where they will attend dinners and parties and balls, and enjoy all those pleasures which ought to have been mine. Mr Strange," she cried, growing more energetic, “surely there must be spells to make the clergyman hate the very sight of Lizzie? To make him shudder at the sound of her voice?"

“I do not know," said Strange. “I never considered the matter before. I suppose there must be." He returned to the list. “ `Mr Bullworth' . . ."

“My husband," she said.

“. . . `To be bitten by dogs.' "

“He has seven great black brutes and thinks more of them than of any human creature."

“ `Mrs Bullworth senior' - your husband's mother, I suppose - `To be drowned in a laundry tub. To be choked to death on her own apricot preserves. To be baked accidentally in a bread oven.' That is three deaths for one woman. Forgive me, Mrs Bullworth, but the greatest magician that ever lived could not kill the same person three different ways."