Joan of Arc (6 page)

The legal case for English kings to be also kings of France rested on the assumption that as the late king’s closest relative, Edward III should have inherited the throne of France. The assumption mattered only because some members of the English royal family were formidable generals. It was not until 1340, backdating his claim to 1337, that Edward declared he was the rightful King of France. It was a derisory assertion until first he beat Philip at Crécy and took Calais, and then his heir, Edward the Black Prince, defeated King John II, Philip’s son and successor, at Poitiers. In 1361, by the Treaty of Brétigny, Edward was conceded sovereignty over the whole of Guyenne, one-third of France, in return for renouncing his claim to France. But that claim was revived when most of the duchy was won back by Charles V (1364–80). In 1369, as Charles prepared to invade Gascony, Edward reasserted his claim to France. On his royal banner, alongside the two lions of Normandy and the single lion of Aquitaine, he placed the lilies of France – which remained there until 1802 – long before the three lions had been nationalised as the emblems of England.

By the time the next English king, Richard of Bordeaux, inherited the English throne in 1377, he did not hold much land near his birthplace in Bordeaux. As an adult Richard II sought a rapprochement with France and to this effect he married Isabella, eldest daughter of Charles VI (1380–1422). He was less skilful in handling his English royal relatives; and when his cousin Henry, Duke of Lancaster, reacted to Richard’s high-handedness by seizing power as Henry IV, Richard’s peace policy towards France became a subject for debate. As a usurper, Henry IV hesitated to intervene, but his successor Henry V (1413–22) was confident he would show that by God’s grace he was the true King of France as well as of England. He prepared to fight.

The second part of the Hundred Years War lasted less than a decade. Henry’s victory at Agincourt in 1415 was effective because he followed it up by overrunning Normandy and negotiating in 1420 a treaty with the spasmodically insane Charles VI. At Agincourt large numbers of the French aristocracy, including brothers of the Duke of Burgundy, were killed and the king’s nephew, Charles, Duke of Orléans, was captured. By this stage only one of Charles VI’s sons had survived, another Charles, as heir or Dauphin. In 1420 at Troyes, however, the father agreed to disinherit his own child and make Henry V his heir. Within a fortnight Henry took the hand of Catherine, Charles VI’s last unmarried daughter. Under the treaty, he also promised to continue with his conquests. To be acknowledged by the French as the next king of France, however, he had to outlive his father-in-law, but Henry died in 1422, some six weeks before Charles VI. His brother John, Duke of Bedford, was named regent for his son in France and his brother Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, regent for his son in England.

Henry V’s victories in France had been aided by infighting within the French royal family. The insanity of their king had encouraged his nearest relations to struggle for power. In 1407 the king’s brother Louis, Duke of Orléans, had been assassinated as a result of a plot by their cousin John, Duke of Burgundy. The Orleanists were known as Armagnacs because of the second marriage of Charles, the new Duke of Orléans, to the Count of Armagnac’s daughter Anne.

Throughout this period there were also rival popes. Louis of Orléans had supported the pope in Avignon, John of Burgundy the pope in Rome. Duke John took the same line as the University of Paris; and after the murder of his cousin there was a pay-off when Jean Petit, a university theologian, defended the killing of Duke Louis as the killing of a tyrant. Louis had behaved in a grand way: he had arranged the marriage of the king’s elder daughter Isabella, widow of Richard II of England, to his own son Charles (his first marriage) and given her an enormous dowry out of royal funds; he had showered himself with royal gifts; he had taken land in north-east France for himself and his supporters; he had also raised unpopular taxes for war against the English. He made it easy for John to be loved in the capital. With Louis out of the way, John made Paris his power base, forced Louis’s sons to be publicly reconciled with himself and purged the government of anyone he did not trust. In the end he overreached himself, however, and at a wrong moment for him, Charles VI recovered his sanity just long enough to favour the Armagnacs, so that even the people of Paris grew restive and John had to retreat to his own lands. His Flemish subjects, many of them involved in the cloth trade, were keen to have good commercial relations with the English, who supplied the cloth, so John was careful to maintain a truce with Henry V; and neither he nor his son Philip rallied to the side of their king at the battle of Agincourt in 1415.

During the chaotic aftermath of that battle, he put loyalty aside and devised a scheme to regain the dominant position in France. In 1417 he persuaded Queen Isabella of Bavaria to join him in setting up a joint government, and in March 1418 he seized Paris. While Henry V took over more and more of northern France and the Dauphin Charles set up his Parlement, or supreme court, in Poitiers and a financial court in Bourges, Duke John had a dilemma: with whom should he ally? At first he favoured the English, but Henry’s capture of Pontoise near Paris made him and the queen withdraw to Champagne. He could not control Henry, but he might control the sixteen-year-old Dauphin. He met Charles for talks on the bridge of Montereau, where the Seine meets the Yonne: there was a scuffle and the duke was stabbed to death. Philip, his son, weighed advice coolly and chose to ally with Henry.

Agincourt and Montereau determined French political events wholly for one decade and largely for two. In 1415 and after 1435 most of the French, except for long-time subjects of the English like the Gascons, fought the English. Between 1415 and 1435, however, they fought each other. When Joan erupted into public life, she assumed that Burgundians were the natural enemies of France. That was what her voices told her, though most Burgundians were French and their duke was the premier peer of France.

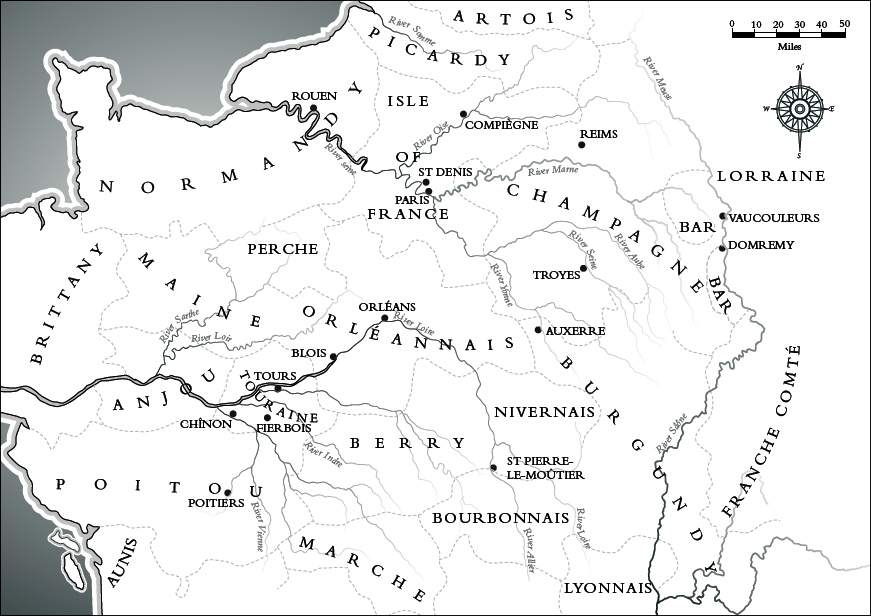

Joan’s political and military career had been determined by events in the 1420s. From 1420 France was effectively divided into three: in the north was English France, centred on Normandy; in the east, Burgundian France (Picardy and Champagne); and to the south of the Loire lay Dauphinist France, refuge of those Frenchmen who had transferred their allegiance from Charles VI to his son. By 1422, Henry V controlled most of the two northern sections and after his premature death it was from this area that his senior surviving brother, Bedford, worked to construct an Anglo-French kingdom for the infant-king Henry. Brother-in-law to Duke Philip, Bedford was just and efficient; and a steady run of victories confirmed his hold on northern France. Charles’s army was cut to pieces beside Cravant in 1423, his trusty Scots constable, James Earl of Buchan, was killed at Verneuil in 1424, and the logic of events persuaded Charles to avoid further military confrontation. While Bedford was in England in 1425–7 stemming a quarrel between his brother of Gloucester and his uncle Cardinal Beaufort, there was a reprieve. At Montargis the bastard of Orléans (half-brother to the captive duke) opened sluice gates to divide the forces of English besiegers and drown half of them, and soon much of Maine was in revolt. But the rising was crushed and in 1428 the English were poised to advance to the heart of Armagnac France and invest the city of Orléans itself. If Orléans fell, France would be bisected; and the richest, most populous parts of the country would be Anglo-Burgundian.

1. France in 1429. Control over France was divided between the English, the Burgundians and the Dauphin.

The best English commander, the Earl of Salisbury, was to direct the siege. On 12 October he was outside the walls. A few days later, however, while inspecting the walls from the twin towers of Les Tourelles, a stray piece of gunshot shattered a window nearby, an iron bar hit his visor and his head was sliced in two. After his death a lesser man, the Earl of Suffolk, took over, and a long, tough siege seemed to lie ahead. Though defended bravely by two generals, La Hire and the Bastard of Orléans in the name of his half-brother the Duke, the city was as hard to save as to take. On 12 February 1429, 500 men, mostly Scots, were beaten by Anglo-Parisian troops. The English already held the lower Seine. Strategically Orléans was the key to the Loire valley but symbolically it was even more important. Whether told by a heavenly or an earthly messenger, Joan was right to say Orléans must not fall. They were also right who held that at Orléans her mission would be tried by battle.

2. Northern and central France, 1429–31. This area is the setting of the story of Joan.

What Need of the Maid?

I

n 1429 Charles’s supporters thought he needed a miracle if his cause was to recover. Those who had struggled for control of France during the past century were all related to one another; and in 1429 Charles looked like the poor relation. To Joan who had not yet met him, he was God’s chosen king, Her passionate convictions about God’s intentions for the kingdom impelled her on to the stage of history when, in May 1428, she arrived at the château of Vaucouleurs and demanded an audience of Robert de Baudricourt, the castellan. A century earlier, the first Valois, Philip VI, had been acknowledged as king. Joan was determined to help Philip’s great-great-grandson to gain recognition too.

She had had to leave Domremy in 1428 when Burgundians raided the village and the church was burnt. Along with her family she took refuge in the nearby village of Neufchâteau. While there she was cited before a Church court in Toul in a case of breach of promise of marriage, a promise she maintained she had never made. Winning the case confirmed her belief in her call to be virginal; and the Burgundian attack gave a new sense of urgency to her mission. To go to a château alone was unthinkable for a young woman, so she made an excuse to visit a pregnant cousin who lived in a little village three miles from Vaucouleurs and then sought the help of her cousin’s husband, Durand Laxart. Laxart was the first person to believe in her. Many years later, he recalled how ‘Joan told me she wished to go into France, to the Dauphin, to have him crowned.’

1

In January 1429 the unlikely pair, a labourer and his cousin by marriage, turned up at Vaucouleurs to see the castellan. Without hesitation, Joan told de Baudricourt that she came in the name of her Lord; Charles must be forced to fight, he would be helped before the end of Lent, the kingdom belonged to her Lord but had been entrusted to the Dauphin, whom she would make king. Who was her Lord, the astonished castellan enquired? When Joan replied ‘the King of Heaven’, de Baudricourt turned to Laxart, told him to take her to her father and to tell him to give her a good whipping.

Historians disagree over whether she went home and came back or whether she stayed on in the town. What is clear is that she grew impatient and decided to set out at once, wearing her ‘uncle’ Laxart’s cast-offs. At the entry into a forest she stopped at the little chapel of St-Nicolas de Septfonds, where, praying before the wooden crucified Christ, she realised she had disobeyed her voices, who had told her to seek the support of de Baudricourt. She went back to Vaucouleurs. As in a good fairy story, she had failed the first time, failed a second time and would succeed the third time; and this is what happened. She now had useful supporters, among them two squires, Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy; she was summoned by the ailing Duke of Lorraine, who probably hoped she would perform a miracle. She told him frankly that she could not oblige, but that, if he gave her an escort, she would pray for him. Back in Vaucouleurs, she learnt from her voices that the French had been routed near Orléans. She told de Baudricourt what had happened and impressed on him the urgency of her journey to the royal court at Chinon. News came from Chinon that if nobody could find evil in her, she should be sent for. On 23 February she appeared in the courtyard of the château of Vaucouleurs, her escort swore their loyalty to the castellan, and, armed with letters for the king, she set off.